![]()

Mon, March 05, 2012 | By M. Kemal Kaya and Svante E. Cornell

This article was first published in the Turkey Analyst, vol. 5 no. 5 (www.turkeyanalyst.org), a biweekly publication of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center. © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center, 2012.

When a special prosecutor attempted to bring in five high intelligence officers (including the head of Turkish intelligence) for questioning, he also cracked the veneer of the AKP’s supposedly consolidated hold on power in the country. Indeed, developments in Turkey since Sadrettin Sarıkaya issued his subpoenas have shown with all clarity a deep split in the ranks of the informal coalition on which the AKP bases its power. That split had thus far been growing but never openly manifested; now, a power struggle between the AKP and the Gülen movement is unraveling. It is unlikely to be easily bridged.

Background

When the AKP won power in the 2002 elections, its newfound position of influence brought together into a tactical alliance two Islamic movements from very different traditions: the Nakshibendi-dominated core of the AKP, and the movement of the preacher Fethullah Gülen. Further, the military e-memorandum published shortly before the 2007 presidential elections brought the two groups even closer together, fearing as they did that the military was poised to move against both groups with full force.

The alliance brought very concrete results in the years that followed. Indeed, it was instrumental in helping the AKP survive the closure case that it confronted in the Constitutional Court in 2008. Following that, it was a key factor in the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer trials that more or less neutralized the forces that opposed and sought to undermine the AKP within the state bureaucracy and in civil society. This in turn made it possible for the AKP to call a referendum to amend the 1982 Constitution, a product of the 1980 military coup, and which had provided the ground for the Kemalist regime. These amendments to a significant degree transferred control of the judiciary to the ruling coalition.

However, as is often the case, the tactical alliance between the AKP and the Gülen movement began to fade once the two groups’ common enemies had been neutralized. As the split between the two is likely to form a central fault line in Turkish politics in coming years, it is important to briefly note wherein their differences lie.

The leadership of the AKP, including Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan and President Abdullah Gül, are products of the political tradition of the Milli Görüş school. They are the heirs of Professor Necmettin Erbakan, the founder and leader of several Turkish Islamic political parties from the late 1960s onward. The core of the movement consists of followers of the Iskender Paşa wing of the Khaledi branch of the Naqshbandi Sufi order. It is important to note that the Nakshbandi order — and in particular the Khaledi branch — differ greatly from most Sufi orders, known in the West for their religious moderation and esoteric nature. The Naqshbandi, one of the world’s largest Sufi orders, is the only one that does not trace its lineage to Ali (the prophet’s cousin and son-in-law, whom Shi’a Muslims believe the prophet appointed to be his successor) but to Abu Bakr, the first Caliph. Thus, the Naqshbandi are firmly within the Orthodox Sunni tradition of Islam. As for the Khaledi branch, named after its seventeeth-century founder Khalid-i Baghdadi, it is most known for having reinforced traditional Islamic tenets of the order, such as adherence to the Sharia and Sunna. Indeed, the Orthodox nature of the Naqshbandis is best illustrated by their fierce resistance to the westernizing reforms of the Ottoman empire in the nineteenth century.

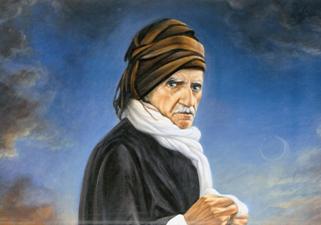

Like other orders, the Naqshbandis were driven underground by the proclamation of the Turkish republic and the closure of the religious orders. Following Atatürk’s death, the Naqshbandis became increasingly involved in politics, seeking to revive religious values in Turkey. Once in politics, they encountered — and were strongly influenced by — the growing political Islamic movement. Figures like Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, Sayyid Qut’b, and the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood movement all had significant intellectual impact on the developing Turkish political Islam. When Necmettin Erbakan (pictured) founded the National Order Party in 1969 on the recommendation of Zahid Kotku, the Iskender Paşa spiritual leader, it reflected the broader Islamic movement of the Middle East, whose views were brought to Turkey by publications edited by Eşref Edip, who lived for a time in Egypt and was deeply influenced by the Brotherhood. Indeed, it was Edip who came up with the name of Erbakan’s party and wrote its political program. Thus, the Milli Göruş movement is deeply rooted in political Islam; its members pay considerably less attention to the Turkish ethnic bond than to the broader Muslim identity.

As for the Gülen cemaat or community, it stems from the Nurcu movement, which has a tradition of strongly objecting to the direct involvement in politics on the part of its members. The Nurcu movement has tended to believe that direct involvement in politics would create a conflict of interest, and weaken the main aim it seeks to instill in its members, known as Imana Hizmet, or “service to the faith.” The successor of the movement’s founder, Bediüzzaman Said Nursi (pictured), kept it as an article of faith to remain loyal to this tradition. Thus, the Nurcu and its offshoot, the Fethullah Gülen community, have traditionally refrained from supporting political Islam. They offered only passive support to Turkey’s successive center-right parties (the Democrat, Justice, Motherland and True Path parties), which supported religious freedom and sought to appeal to conservative Muslims. They never extended their support to Erbakan. Said Nursi even overtly expressed his disapproval of his friend Edip’s establishment of an Islamic Democratic Party in 1951.

Gülen (pictured) followed the Nurcu tradition of refraining from establishing political parties. But he also developed a new outlook. While the traditional Nurcu movement was skeptical of Turkey’s modernization, Gülen’s movement sought to synthesize traditional Islam and Turkey’s modernization. Gülen worked out of Izmir on the Aegean coast, perhaps Turkey’s most modern and liberal region. The Gülen movement, like the Aegean as a whole is strongly influenced by persons with an origin in the Balkans, who settled widely in the region. Many were active in the Turkish nationalist organizations, known in Turkish as ülkücü or “idealist”, prior to the 1980 military coup, but joined Gülen’s organization in the 1980s. Indeed, many nationalists were profoundly affected by the growing international reach of Gülen’s schools, in which the Turkish language kept a prominent role.

This Turkish nationalist element of the Gülenist movement is important: as its members have risen in the ranks of the police and judiciary bodies in the past decade, they have contributed to maintaining the statist views embraced by these institutions. Especially among Gülen followers working in the eastern and southeastern regions of Turkey and dealing with the Kurdish issue, such Turkish nationalist views have been reinforced. It is telling that while the leader of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), Devlet Bahçeli, uses harsh rhetoric against the Gülen movement, the Gülenists have not reciprocated, refraining from taking a stand against the MHP.

Implications

These diverging perspectives came to clash on a number of issues both domestic and international. Undoubtedly, the Kurdish question is leading among them. The AKP’s Kurdish opening (See 17 August 2009, 26 October 2009, 11 October 2010 issues of the Turkey Analyst) was supported by the party’s Islamist and liberal forces, who shared a tendency to downplay Turkish ethnic identity and seek solutions that went beyond those espoused by the traditional Turkish establishment, which refused to compromise on the country’s unitary structure and the primacy of the Turkish language. However, the void left in state institutions by the military-secular establishment’s decline was filled largely by Gülenists, who shared the nationalist reflexes of their predecessors.

On the foreign policy front, differences developed in a slightly different way. As Gülen expanded his horizons beyond Turkey, he and his followers became increasingly sensitive to the broader balances and nuances of world politics. In a sense, his international network of educators and businessmen led the movement to become globalized. As a result, the movement stands out by the absence of the anti-Western, anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic reflexes that are so prevalent among Islamic political groups worldwide, not least the Milli Görüş and the AKP. This divergence of perceptions became painfully obvious following the 2010 Gaza flotilla incident, which rocked Turkey and led to sharp and enduring anti-Israel rhetoric from the AKP’s leaders, almost bringing the relations between the countries to a breaking point.(See 26 October 2009 and 12 September 2011 issues of the Turkey Analyst.) In an interview to the Wall Street Journal that initially even shocked many of his supporters, Gülen stated his disapproval of the flotilla initiative — terming it a ‘defying of authority’ for failing to seek Israeli approval for its delivery of aid. Similarly, media outlets supportive of Gülen have long been scathing in their rhetoric against the Iranian and Syrian regimes, in a way that has often generated disbelief among the traditional Islamists in the AKP. Indeed, the Gülenists worked to undermine AKP Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu’s efforts to improve ties with Iran, and were among the main forces to push for a harsher line against Bashir al-Assad.

The September 2010 constitutional amendments had the effect of empowering the Gülenists in the judicial institutions. The reason is simple: the Milli Görüş movement has few followers with the secular education required to fill high judicial positions, as its members are generally trained in imam-hatip schools. Education, by contrast, has always been the trump card of the Gülenists. Perhaps as a result of this, the movement’s growing power appeared to rattle Erdoğan, who remains determined to eliminate any rival center of power in the country. Thus, when Erdoğan prepared the party list ahead of the June 2011 election, few of the estimated 60 or 70 Gülen supporters were left in place. While this was not widely reported at the time, it led to serious dissonance within the Gülen movement. Meanwhile, the wholesale reform of public administration that the AKP government embarked upon was used as an excuse to remove or circulate many Gülenists in the state bureaucracy — particularly in the Ministry of Education, which is dear to the movement’s heart.

Finally, yet another element of discord has been in the realm of business. Businesses close to the AKP have profited tremendously from public procurement, and the levels of corruption involved in this sector are staggering. It is no coincidence that Turkey has made no effort to move toward EU harmonization in this sector. Nevertheless, Gülen-aligned businesses have increasingly felt left out from state contracts that have gone largely to Erdoğan loyalist companies.

Conclusions

It is clear that the AKP and the Gülen movement have now split ways, leaving in shatters the tactical alliance that was launched in 2002 and deepened considerably in 2007. Ideological elements are an important cause of the split: the two groups’ views on key question such as the Kurdish issue, Iran and Israel are often incompatible. But in the final analysis, this is yet another struggle for power, for control of the Turkish state. The Gülenists feel that they have not received appropriate remuneration for their support, without which Erdoğan and the AKP might not be in power today. Conversely, Erdoğan decided to bring to a halt the expansion of the Gülen movement’s power within state institutions — partly as it threatened to overtake the AKP itself and become a state within the state, but partly simply because he now could, having used the Gülenists to eradicate their common enemies.

At present, both sides are trying hard to tone down their differences and to mend fences following the altercation over the intelligence services. But no one should be fooled by this veneer: the split is out in the open, and it is a divide that could well develop into one of the chief fault lines of Turkish politics in the coming years, with considerable implications. While a cease-fire may have been called, the differences between the two groups are deep, and unlikely to be easily bridged.

M. Kemal Kaya and Svante E. Cornell are Senior Fellow and Research Director, respectively, with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center.

RSS

RSS

[…] discussed in the March 5, 2012 Turkey Analyst, there are significant differences between the two Islamic visions; in foreign […]

[…] not its supporters. In this endeavor, it has enjoyed — until recently (See Turkey Analyst, 5 March 2012) — the support of the movement named after Islamic preacher Fethullah Gülen. Gülen’s […]