![]()

By Richard Breitman and Norman J.W. Goda

In 1998 U.S. Congress passed the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act as part of a series of efforts to identify, declassify, and release federal records on the perpetration of Nazi war crimes and on Allied efforts to locate and punish war criminals. As a consequence, U.S. Congress charged the National Archives in 2009 to prepare an additional historical volume as a companion piece to its 2005 volume U.S. Intelligence and the Nazis. Professors Richard Breitman and Norman J. W. Goda note in Hitler’s Shadow that these CIA & Army records produced new “evidence of war crimes and about wartime activities of war criminals; postwar documents on the search for war criminals; documents about the escape of war criminals; documents about the Allied protection or use of war criminals; and documents about the postwar activities of war criminals”. The following essay [Nazis and the Middle East] is part of a volume of essays under the title Hitler’s Shadow – Nazi War Criminals, U.S. Intelligence, and the Cold War published by the National Archives. This government publication is considered to be in the public domain, however it is the user’s responsibility to determine copyright. You can download the full document [PDF] here.

Rashid Ali al-Gaylani and Haj Amin al-Husseini speaking at the anniversary of the 1941 pro-Nazi military coup in Iraq in front of black-white-green banners in Berlin (Credit: Yad Vashem)

Recent scholarship has highlighted Nazi aims in the Middle East, including the intent to murder the Jewish population of Palestine with a special task force that was to accompany the Afrika Korps past the Suez Canal in the summer of 1942.[1] Scholars have also re-examined the relationship between the Nazi state and Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, as well as the postwar place of the Holocaust in Arab and Muslim thinking.[2] Newly released CIC and CIA records supplement this scholarship in revealing ways.

Einsatzkommando Egypt

The 1946 testimony of Franz Hoth casts interesting light on both Nazi territorial objectives and Jewish policy in 1940–42. British troops in Norway captured Hoth, an SS and Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service or SD) officer who had served in a number of different mobile killing units called Einsatzkommandos.[3] When in March 1946 British interrogators asked Hoth about the functions of the Einsatzkommandos, he studiously avoided giving self-incriminating statements. His interrogator seems to have liked him: “Hoth declares — and the interrogator is inclined to believe him — that throughout his SD career, he tried to work in accordance with his ideals. It is not thought that Hoth would consciously have made himself guilty of any crimes….”[4] As a result of this generous assessment, his interrogator let him get away with many evasive answers.

Nevertheless, Hoth gave useful background about the early 1941 training of police officers slated for deployment in Africa when Germany expected to establish a raw materials empire there. At the Security Police School in Berlin-Charlottenburg, medical experts, Foreign Office officials, and other experts lectured to three classes of about 30 police officers each; additional classes were held for non-commissioned officers. “The purpose of these courses was to make the students familiar with the history and problems of the former German colonies in preparation for the day when these colonies would be retrieved by Germany,” Hoth explained. Afterwards, all the German police officers went to Rome (April 1941), attending an Italian police school where they learned how the Italian police handled resistance in the Italian African colonies.[5]

Hoth was friendly with a senior official of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) named Walter Rauff, one of the inventors and distributors of the gas van used to asphyxiate victims in Belarus and later at the Chelmno extermination camp. Because of his connection with Rauff, who was slated for command of an Einsatzkommando in North Africa, and his colonial training, Hoth was appointed head of section I of Rauff’s Einsatzkommando Egypt, which was assembled and dispatched to Athens in July 1942. There the unit waited for General Rommel’s troops to conquer Egypt and move into the British-controlled Mandate of Palestine, where roughly half a million Jews lived.[6]

Rauff’s Einsatzkommando, technically subordinated to Rommel’s army, reported directly to the RSHA in Berlin. After Reinhard Heydrich was assassinated in Czechoslovakia, SS chief Heinrich Himmler took direct command of this umbrella security-police organization. Two German historians have indicated that Himmler conferred with Hitler about the deployment of Einsatzkommando Egypt, which was to take “executive measures” against civilians on its own authority, in other words, the mass murder of Jews.[7] In 1946 Hoth commented only that his Einsatzkommando was supposed to perform the usual Security Police and SD duties in Egypt; he avoided saying that such duties elsewhere had included the mass execution of Jews. But this context puts a rather different light on what his British interrogator called Hoth’s idealism.

Hitler himself signaled his intention to eliminate the Jews of Palestine. In a November 28, 1941, conversation in Berlin with Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hitler said that the outcome of the war in Europe would also decide the fate of the Arab world. German troops intended to break through the Caucasus region and move into the Middle East. This would result in the liberation of Arab peoples. Hitler said that Germany’s only objective there would be the destruction of the Jews.[8]

The British never prosecuted Hoth for his Einsatzkommando activities. But he had also served in the Security Police in the French city of Nancy, and the French military authorities found him guilty of crimes there. He was sentenced to death and executed in 1949.[9]

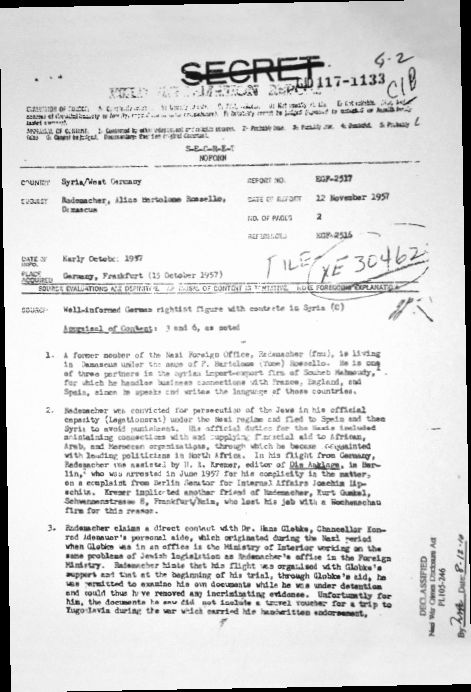

German financial support of Arab leaders during the entire war was astonishing. The Grand Mufti Amin el Husseini and Raschid Ali El Gailani financed their operations with funding from the German Foreign Ministry from 1941–45. German intention in the Arab countries was based on an expectation of establishing pro-German governments in the Middle East. (RG 319, Records of the Army Staff).

New Documentation: Haj Amin al-Husseini’s Contract

Recent books have added greatly to our knowledge of Haj Amin al-Husseini’s activities as leader of anti-Jewish revolts in the British Mandate in Palestine in 1929 and 1936, as the impetus behind the pro-German coup in Iraq in April 1941, and as a pro-Nazi propagandist in Berlin, broadcasting over German short-wave radio to large audiences in the Middle East starting in late 1941.[10] CIA and U.S. Army files on Husseini offer small pieces of new evidence about his relationship with the Nazi government and his escape from postwar justice.

The Nazi government financed Husseini and Rashid Ali el-Gailani, the former premier of Iraq who had joined Husseini in Berlin after his failed coup in Iraq. After the war Carl Berthold Franz Rekowski, an official of the German Foreign Office who had dealt with Husseini, testified that the Foreign Office financially supported the two Arab leaders, their families, and other Arabs in their entourage who had fled to Germany after the coup. Husseini and Gailani determined how these funds were distributed among the others. The CIA file on Husseini includes a document indicating that he had a staff of 20–30 men in Berlin. A separate source indicates that he lived in a villa in the Krumme Lanke neighborhood of Berlin. From spring 1943 to spring 1944, Husseini personally received 50,000 marks monthly and Gailani 65,000 for operational expenses. In addition, they each received living expenses averaging 80,000 marks per month, an absolute fortune. A German field marshal received a base salary of 26,500 marks per year.[11] Finally, Husseini and Gailani received substantial foreign currency to support adherents living in countries outside Germany.[12]

Through conversations with other Foreign Office officials, Rekowski learned that Nazi authorities planned to use both Arab leaders to control their respective countries after Germany conquered them. Gailani was an Iraqi nationalist who maintained good ties with the German Foreign Office. Husseini, however, was a believer in a Pan-Arab state. His closest ties were with the SS. The other Arabs were divided into one camp or the other.

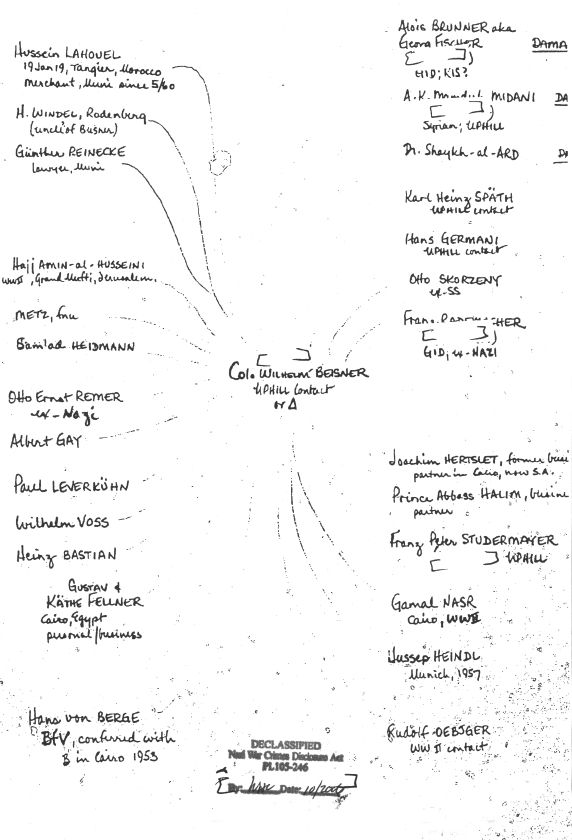

SS-Sturmbannführer Wilhelm Beisner, like Hoth, an officer on Einsatzkommando Egypt, had frequent contact with Husseini during the war.[13] Beisner told Rekowski that Husseini had good ties with Himmler and with Waffen-SS Gen. Gottlob Berger, who handled the recruitment of non-German forces into the Waffen-SS. SS leaders and Husseini both claimed that Nazism and Islam had common values as well as common enemies—above all, the Jews.[14]

Another independent source of information on Husseini’s ties with the SS was the disaffected and abused wife of a young Egyptian, Dr. Abdel Halim el-Naggar, who had worked in Berlin for the German Foreign Office and the Propaganda Ministry. An Egyptian named Galal in Berlin edited an Arabic-language periodical designed to stir up the Arabs to support Germany, and el-Naggar assisted him in 1940. By 1941 el-Naggar had his own Arabic publication for Middle Eastern audiences, and in 1942 he took on the additional job of director of Nazi short-wave broadcasts to the Near East. After Husseini came to Berlin, he wanted to cooperate with el-Naggar on Middle Eastern broadcasts, and for a time they worked together successfully. Then el-Naggar established an Islamic Central Institute in Berlin. Husseini had wanted to head this institute, and after el-Naggar refused him, Husseini used his influence with the SS to get el-Naggar removed from the broadcasting job.[15]

In the fall of 1943 Husseini went to the Independent State of Croatia, a Nazi ally, to recruit Muslims for the Waffen-SS. During that trip he told the troops of the newly formed Bosnian-Muslim 13th Mountain Waffen-SS division that the entire Muslim world ought to follow their example. Husseini also organized a 1944 mission for Palestinian Arabs and Germans to carry out sabotage and propaganda after German planes dropped them into Palestine by parachute. In discussions with the Foreign Intelligence branch of the RSHA, Husseini insisted that the Arabs take command after they landed and direct their fight against the Jews of Palestine, not the British authorities.[16]

Today we have more detailed scholarly accounts today of Husseini’s wartime activities, but Husseini’s CIA file indicates that wartime Allied intelligence organizations gathered a healthy portion of this incriminating evidence. This evidence is significant in light of Husseini’s lenient postwar treatment.[17]

In the spring of 1945, a German Foreign Office official reached agreement with Gailani effective April 1: his cash payments were raised to 85,000 marks, but Gailani would repay the Germans after his forces reconquered Iraq. Similarly, according to a newly declassified document, the Foreign Office and Husseini signed a contract for subsidies of up to 12,000 marks per month to continue after April 1, 1945, with the Mufti pledging to repay these amounts later. In April 1945 neither side could have had much doubt about the outcome of the war. The continuing contractual relationships meant that Nazi officials and the two Arab leaders hoped to continue their joint or complementary political-ideological campaign in the postwar period.[18]

Declassified CIA and Army files establish that the Allies knew enough about Husseini’s wartime activities to consider him a war criminal. Apparently fearing Allied prosecution,[19] he tried to flee to Switzerland at the end of the war. Swiss authorities turned him over to the French, who brought him to Paris.

The CIA diagram shows a nexus of former Nazis––Beisner, Skorzeny, Rademacher, Brunner and Remer — with important Arab leaders –– the Grand Mufti Hajj Amin el Husseini, Abbass Halim, and Gamal Nasser. (RG 263, Central Intelligence Agency).

Haj Amin al-Husseini’s Escape

Right after the war ended a group of Palestinian-Arab soldiers in the British Army who were stationed in Lebanon had staged anti-French demonstrations. They carried around a large picture of Husseini and declared him to be the “sword of the faith.”[20] According to one source considered reliable by the rump American intelligence organization known as the Strategic Services Unit (SSU), British officials objected to French plans to prosecute Husseini, fearing that this would cause political unrest in Palestine. The British “threatened” the French with Arab uprisings in French Morocco.[21]

In October 1945 Arthur Giles (who used the title Bey), British head of Palestine’s Criminal Investigation Division, told the assistant American military attaché in Cairo that the Mufti might be the only person who could unite the Palestine Arabs and “cool off the Zionists…. Of course, we can’t do it, but it might not be such a damn bad idea at that.” French intelligence officials, bitter at France’s loss of colonial territory in the Middle East, said they would enjoy having the Mufti around to embarrass the British.[22]

Husseini was well treated in Paris. Meanwhile, Palestinian Arab leaders and various Muslim extremists agitated to bring him back to the Middle East. According to the American military attaché in Cairo, this plan initially embarrassed moderate officials in the Arab League. But as prospects for a peaceful settlement in the British Mandate for Palestine declined and as other Arab prisoners were released or escaped (Gailani escaped), sentiment changed. A delegate of the Palestine Higher Arab Committee went to Paris in June 1946 and told Husseini to get ready for a little trip.[23]

According to another American source in Syria, at a meeting in the Egyptian Embassy in Paris, the ambassador, the ministers of Syria and Lebanon, and a few Arab leaders from Morocco and Algeria worked out the details of Husseini’s escape. The French government learned of, or was informed of, the plan, but chose not to intervene in order to avoid offending the Arabs of North Africa. Husseini flew to Syria, then went via Aleppo and Beirut to Alexandria, Egypt.[24]

By 1947 Husseini denied that he had worked for the Axis powers during the war. He told one acquaintance that he hoped soon to have documentary evidence rebutting this slander, which the Jews were spreading. Similarly, after Adolf Eichmann was brought to Israel for trial in March 1961, Husseini, by now in Beirut, denied having ever met Eichmann during the war. He said that he had been forced to take refuge in Germany simply because British wanted to capture him. Nazi persecution of Jews had served Zionism, according to Husseini, by exciting world sympathy for them. Husseini never worked for American intelligence; the CIA simply considered him a person worth tracking. He died in Beirut in 1974.[25]

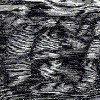

Franz Rademacher –– linked to the persecution of Jews –– fled first to Spain and then to Syria, It is believed that Hans Globke, Adenauer’s personal aide, assisted his escape. (RG 319, Records of the Army Staff).

Wilhelm Beisner, Franz Rademacher, and Alois Brunner

The CIA and the CIC both compiled files on the versatile and French-speaking Wilhelm Beisner, who dealt with Husseini during and after the war. It is possible to trace Beisner’s long intelligence career better than has been done before. His tracks after the war intersected with those of German Foreign Office deportation specialist Franz Rademacher, and Adolf Eichmann’s subordinate Alois Brunner. All three spent most of their postwar years in the Middle East.

In April 1945 an unnamed German defected to Switzerland and offered up Beisner as a war criminal of Allied interest. Although Allen Dulles’s office did not trust the informant, they rated his information good.[26] According to this report, Beisner trained as an agronomist, then went into Alfred Rosenberg’s Nazi Party Foreign Policy Office (Aussenpolitisches Amt), becoming a specialist in the Balkan region. He was allegedly involved in the Iron Guard’s unsuccessful January 1941 coup in Bucharest –– a Romanian “Kristallnacht” in which 120 Jews were brutally murdered. The informant mistakenly placed Beisner as head of the Gestapo in Lodz and Zagreb. Beisner did, however, serve a term in the Waffen-SS, where he was assigned to the Selbstschutz, a “self-defense” force of ethnic Germans used to carry out brutal and murderous policies in German-occupied Polish territory.[27] Although his SS personnel file lacks evidence of it, from the spring of 1941 until late that year he served in Croatia as head of an Einsatzkommando Zagreb (part of Einsatzgruppe Yugoslavia). Croatian sources list him also as German police attaché to the new Independent State of Croatia.[28]

The Ustaschi government in Croatia admired the SS and was eager to win Himmler’s favor, according to the Croatian minister in Berlin.[29] The period Beisner was in Croatia was precisely the period when the Croatian Ustaschi engaged in massive killings of Jews and Serbs. In January 1942 Beisner received the German war cross of merit, second class, for his service, and in 1943 the Croatian government decorated him as well.[30]

At the end of 1941 Beisner joined SD Foreign Intelligence as a specialist in the Middle East. Assigned as an officer to Einsatzkommando Egypt, he went to Athens to await Rommel’s conquest of Egypt.[31] After Rommel’s defeat, he then shifted to Tunis, where he commanded a Security Police and SD unit and served as liaison to the Grand Mufti.[32] He also set up an intelligence network in Tunis, which French intelligence sources reported on in some detail. When German forces had to evacuate Tunisia, Beisner went to Italy, and he tried to keep his Tunisian network running. In fact, he sought intelligence covering the Near East generally.[33]

He spent the last part of the war in Italy, where American forces apparently captured him. Gehlen Organization sources later said Beisner escaped from American internment with French help and then went to work for French intelligence in Austria.[34] In late 1950 an Austrian official who located Beisner in Munich asked the CIA for information about him. A CIA official thought Austrian interest stemmed from their belief that Beisner was working for West German intelligence. The CIA post in Karlsruhe reported that Beisner had a business enterprise in Munich named Omnia that probably served as cover for French intelligence activities.[35]

A West German intelligence report in March 1952 indicated that Beisner had been involved in black-market arms transactions among Switzerland, Spain, and France. Discovery of these activities forced him to go to Cairo, where he allegedly continued to work for the French and enjoyed good connections with the Americans as well. (CIA did not think much of that last comment.) He seems to have been active in purchasing arms for the Egyptian government.[36] Another CIA document indicated that Beisner arrived in Cairo on July 21, 1951, as representative of a Hamburg firm called Terramar and that he offered his services to the Gehlen Organization.[37]

By then other Germans had arrived in Egypt. In December 1952 the West German ambassador to Egypt, speaking to the press in Bonn, drew a clear distinction between German military advisers in Egypt and former Nazis in certain Middle Eastern countries linked with Haj Amin al-Husseini; these Nazis were working to impair relations between Arab states and West Germany, incite disturbances, and spread chaos.[38]

In Cairo, Beisner did resume contact with Haj Amin al-Husseini. Al-Husseini helped him get a visa for a Polish Jew named Hertslett, who worked with Beisner in the Egyptian Continental Trading Company, a firm involved in arms deals and illicit traffic. According to information CIA received through an Italian business contact of Beisner, Prime Minister Najib of Egypt used Beisner to negotiate a large purchase of machine guns and cannons, which were to be routed through Spain if the United States did not object.[39] Later that year, the economic section of the American Embassy in Egypt warned that the Egyptian Continental Trading Company had a bad reputation. Beisner and Hertslett had tried to pass themselves off as working on behalf of the West German government to foster trade between West Germany and Egypt; they were now blacklisted and had little means.[40] The CIA had no direct contact with Beisner. Most of the CIA’s information about his Egyptian activities originated with the Gehlen Organization.[41]

In 1954 the CIC received a report that Beisner was running Egyptian intelligence operations for an organization called the Institute for Contemporary Research (Institut für Gegenwartsforschung). This institute was likely connected with a shadowy West German intelligence organization run by Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz called the Amt Blank. The CIC checked Beisner’s SS Personnel records at the Berlin Document Center, but they were fragmentary.[42]

Beisner’s importance grew in February 1958 when Franz Rademacher, living in Damascus under a pseudonym, told an unnamed CIA source in Syria that Gamal Abdel Nasser (called Jamal Nasir in one document and Gamal Nasir in another) had worked for the Germans during the war, and that Beisner had served as his liaison. They still were close, Rademacher claimed.[43]

After leading a revolution and becoming the second president of Egypt in 1956, Nasser had established an intelligence organization under Zakaria Mohieddin. Zakaria had chosen Beisner’s former RSHA comrade Joachim Deumling as his intelligence adviser. Deumling had worked for the British Army of the Rhine after the war, but the British blacklisted him for security reasons in 1951.[44] When he decided to leave West Germany for Egypt, he traveled secretly to avoid attracting British attention. Zakaria, who soon became minister of the interior as well, praised Deumling’s intelligence work in Egypt.[45]

Beisner may have benefited from an increasing presence of former Nazis in Cairo under Nasser. He later claimed that while in Cairo he had helped to train Algerian volunteers for the struggle to liberate Algeria from French control and that he sold arms to the Algerian National Liberation Front.[46] Whether he operated on his own or with Egyptian intelligence approval is unclear.

In March 1958 an unnamed CIA source contacted Beisner through Rademacher in Syria nominally to get assistance on a possible contract to build radar stations in Saudi Arabia. Impressed with Beisner’s acumen, the man asked the CIA if it would like him to pursue a business relationship with Beisner. CIA officials saw a number of unanswered questions about Beisner and concluded that the source could pursue a business relationship with him without any Agency involvement.[47]

Rademacher’s own route to the Middle East was convoluted. In 1952 West German authorities had lodged charges against Rademacher for his involvement in the murder and deportation of Jews in several countries. Although acquitted of many of the charges in spite of substantial evidence against him, he was sentenced to three years for his role in arranging deportations of Jews from Serbia and eight months for being an accessory to similar activity in Belgium. After West German authorities released him on bail during his appeal, he went into hiding, eventually fleeing to Spain and then Syria.[48] In 1957 Rademacher hinted to a right-wing German with good contacts in Syria that Konrad Adenauer’s aide Hans Globke, with whom Rademacher had worked during the war, had assisted his flight from West Germany. He also claimed a good connection with the chief of Syrian intelligence. His formal position in Damascus was partner in the import-export firm of Souheb Mahmoudy, and he used the name of a Spaniard, Bartolomé Rossello. The CIC source mentioned Rademacher’s contacts with a “Beischner” and an “Otto Fischer,” about whom Rademacher was unwilling to say much.[49]

By 1959 the CIA had tentatively concluded that Beisner was a source for West German intelligence. A high BND official codenamed Winterstein conceded that the BND had a loose relationship with Beisner, meaning it had contact with him, but could not really direct him or his activities. But the BND kept in mind that, given his frequent travels and contacts, it was likely Beisner had a close connection with Egyptian intelligence.[50]

In October 1960, while in Munich, where his wife kept an apartment, Beisner was wounded when a bomb exploded in his car. West German police speculated that the French terrorist organization called the Red Hand had carried out the attack. A BND official told CIA that, in his personal opinion, Beisner worked for Egyptian intelligence, and that the Red Hand had arranged the explosion. Beisner’s vision was damaged, and he lost a leg. Today, we know that the Red Hand was a unit sponsored by the French Intelligence (Documentation and External Counterespionage Service or SDECE) to carry out assassinations and attacks against the Algerian liberation movement.[51]

By then, Beisner had fallen into disfavor in Egypt, possibly because of general distrust of foreigners, or more likely because of dissatisfaction with how he had handled commissions on his arms deals.[52] As a result of his difficulties, Beisner wrote a man using the name Georg Fischer or Rischer in Damascus to see whether he would be welcome in Syria. In his handwritten reply, “Rischer” said that his friends would be happy to talk with Beisner face-to-face, and he himself would be pleased to see Beisner. “Rischer” also complained about a recent article that slandered Egypt, Syria, and their leading officials. He said it very much resembled Zionist propaganda against Nazi Germany after 1936![53]

An intelligence agency intercepted the mail to Alice Beisner’s Munich apartment and passed copies to the CIA. (Although the BND said that it was a French intercept operation, the CIA thought that the BND itself might have done it.) As a result, the CIA read “Rischer’s” reply. CIA officials concluded, after comparing handwriting, that Rischer was really Alois Brunner, Adolf Eichmann’s onetime subordinate, who was now serving as an adviser to Syrian intelligence. In subsequent correspondence Rischer strongly recommended that Beisner read Simon Wiesenthal’s new book I Hunted Eichmann.[54]

CIA officials received other indications that Fischer/Rischer was Brunner.[55] A CIA official in Munich had an informal discussion in March 1961 with a BND official codenamed Glueckrath, who claimed that a grand council of the Egyptian SS group had met several times in late 1960 and January 1961. Brunner had attended, along with Fritz Katzmann, former Higher SS and Police Leader in Galicia, who had gone into hiding at the end of the war and escaped justice. Other participants named were former Nazi propagandist Johannes von Leers, a major from Egyptian intelligence, and a lieutenant colonel from the Egyptian Ministry of Information. At this meeting Brunner claimed to possess a long list of Jews who had collaborated with the Nazis during the Final Solution; they could now be blackmailed to help finance the SS group. Von Leers said that if this blackmail failed, he at least wanted to publish the list.[56]

Beisner ended up resettling in Tunis, not Damascus. CIA last traced him there in 1966, still wheeling and dealing. Rademacher was put on the payroll of the West German Secret Service sometime in 1961 or early 1962. The CIA was aware of Rademacher’s status with the BND and interested in his activities, but had no direct contact with him.[57]

After France intercepted a shipment of arms to Algerian liberation forces, Rademacher was suspected of having leaked the information. Syrian authorities arrested him for spying. Thrown into prison, he was released in 1965 because of poor health—he had suffered two heart attacks in prison. He decided to return to West Germany in September 1966, where he was tried again, convicted, and given a five-year sentence. However, the judges gave him more than full credit for time served in American internment after the war. He died as a free man in 1973.[58] Alois Brunner survived an assassination attempt and remained in Syria –– the last member of Adolf Eichmann’s team. He apparently died there in 1992.[59]

Beisner, Rademacher, Brunner, Deumling, and a number of other former SS and police officials found not only havens, but postwar employment in Middle Eastern countries. There they were able to carry on and transmit to others Nazi racial-ideological anti-Semitism. Beisner, Rademacher, and particularly Brunner played important roles in the systematic killing of millions of Jews, and they continued to fulminate about Jewish influence decades later.

Much of the evidence of their postwar influence in Middle Eastern countries comes from their own statements. Driven by Nazi obsessions, these men never had a clear grasp of objective political realities, and they may also have exaggerated their postwar influence. Others who talked about them are far from perfect sources. Still, these intelligence reports, cross-checked against each other, are all the documentary sources we have about them. Perhaps one day the opening of archives in Middle Eastern countries will allow further insight into how far their influence went.

![]()

Notes:

[1] Klaus-Michael Mallmann and Martin Cüppers, Nazi Palestine: The Plans for the Extermination of the Jews of Palestine (New York: Enigma Press, 2010).

[2] Jeffrey Herf, Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

[3] On Hoth’s career, see Report on Interrogation of SS-Sturmbannführer Franz Hoth, March 15, 1946, PWIS (Norway)/81, NARA, RG 319, IRR Hoth, Franz, D 033387. This file is newly declassified in the United States but may have been available in the United Kingdom and Germany earlier.

[4] Report on Interrogation of SS-Stubaf. Franz Hoth, March 15, 1946, PWIS (Norway)/81, NARA, RG 319, IRR Hoth, Franz, D 033387.

[5] Interrogation of Hoth, March 15, 1946/PWIS (Norway)/83, NARA, RG 319, IRR Hoth, Franz, D 033387.

[6] Mallmann and Cüppers, Nazi Palestine, pp. 117–18.

[7] Mallmann and Cüppers, Nazi Palestine, pp. 117–18.

[8] See discussion in Jeffrey Herf, Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World, pp. 76–78, and Mallmann and Cüppers, Nazi Palestine, pp. 89–91.

[9] Mallmann and Cüppers, Nazi Palestine, p. 206.

[10] Herf, Nazi Propaganda, passim; Klaus Gensicke, Der Mufti von Jerusalem und die Nationalsozialisten (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. 2007); Hillel Cohen, Army of Shadows: Palestinian Collaboration with Zionism, 1917–1948 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

[11] See Norman J.W. Goda, “Black Marks: Hitler’s Bribery of His Senior Military Officers,” Journal of Modern History, v. 72, n. 2 (June 2000): 413–52.

[12] Final Interrogation Report of Rekowski, August 23, 1945, Annex III, August 14, 1945, Prominent Arabs in Germany, NARA, RG 319 IRR Rekowski, Carl Berthold, XA 20393; Document XX-8002, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 58, Haj Amin al-Husseini Name File, vol. I, part 1. The source on Husseini’s villa is Account in German by Mrs. el-Naggar [June 1946], NARA, RG 319, IRR Naggar, Abdel Halim el, D 052707.

[13] Beisner’s story is presented below.

[14] Herf, Nazi Propaganda, 200.

[15] Account in German by Mrs. el-Naggar [June 1946], NARA, RG 319, IRR Naggar, Abdel Haleim el, D 052707. El-Naggar went back to working for the Propaganda Ministry and the Foreign Office. Near the end of the war he moved to Prague. He beat his wife (again) badly after she failed to destroy all the documents in his Berlin apartment that connected him with the Nazi regime.

[16] Document XX-8830, old pouch, November 1-26,1944, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 58, Haj Amin al-Husseini Name File, v. 1, f. 1.

[17] Wash X-2-Int-49 Balkan Censorship folder 1, March 15, 1944, and Document XX-8002, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 58, Haj Amin al-Husseini Name Fil, v. 1, f. 1.

[18] NARA, RG 319, IRR Grand Mufti, Agreement with German Reich, MSN 53144.

[19] Report BX-181 from Bern, May 17, 1945, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 58, Haj Amin al-Husseini Name File, v. 1, f. 1. Zvi Elpeleg, The Grand Mufti, Haj Amin al-Hussaini, Founder of the Palestinian National Movement (London: Frank Cass, 1993), pp. 76–77, Husseini’s fear of being prosecuted at Nuremberg increased when he learned that Hermann Krumey gave written evidence in Switzerland that Husseini was involved in encouraging the Nazi destruction of the Jews.

[20] OSS R &A document 1090, May 26, 1945, copy in NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 58, Haj Amin al-Husseini Name File, v. 1, f. 1.

[21] Gensicke, Der Mufti von Jerusalem und die Nationalsozialisten, 148. Burrell to Blum, March 7, 1946, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 58, Haj Amin al-Husseini Name File, v. 1, f. 1.

[22] Floyd A. Spencer, Asst. Military Attaché, Cairo Report, Background of Plan to Return … Husseini to Middle East, June 21, 1946, NARA, RG 165, Army G-2 3161.0503, MIS 279421.

[23] Floyd A. Spencer, Asst. Military Attaché, Cairo Report, Background of Plan to Return … Husseini to Middle East, June 21, 1946, NARA, RG 165, Army G-2 3161.0503, MIS 279421.

[24] The Escape of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, August 2, 1946, NARA, RG 263, Grumbach Series 12, Finished Reports. We are grateful to Randy Herrschaft for this reference.

[25] Palestine: Views of Mufti: Desire for British Neutrality. Remarks of the Mufti to an experienced Arab source, May 14, 1947, and Reuters article of March 4, 1961, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 58, Haj Amin al-Husseini Name File, v. 1, f. 1 and v. 2, f. 1.

[26] Bern Report B-2461, April 12, 1945, copy in NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File. The CIA file name is based on a confusion about his first name Wilhelm and middle name Friedrich. It also misspells Beisner, something that Nazi officials themselves often did. We have followed the CIA’s spelling and name errors in footnotes using the CIA file.

[27] SS Personnel Main Office to Beissner [sic], September 28, 1939, copy in NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[28] Mallmann and Cüppers, Nazi Palestine, 81. See also Ivo Goldstein and Slavko Goldstein, Holokaust u Zagrebu (Zagreb: Novi Liber, 2001), 266, 583, 584.

[29] Gottlob Berger to Himmler, April 12, 1941, NARA, RG 242, microcopy T-175, reel 123, frame 2648997.

[30] Verleihung eines Kroatischen Ordens, October 16, 1943, NARA, RG 242, microcopy A-3343, SS Officer Files, reel 54.

[31] Mallmann and Cüppers, Nazi Palestine, 118.

[32] Traces, November 10, 1949 and Nachrichtenagent Willi Beissner, May 9, 1950, both in NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File. The information in the second document stemmed from the Gehlen Organization.

[33] French North Africa — Tunis — German Intelligence Service During Occupation, November 15, 1944; Saint London to Saint Washington, July 17, 1944; NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[34] Nachrichtenagent Willi Beissner, May 9, 1950, both in NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[35] Chief of Station Vienna to Chief of Station Karlsruhe, December 8, 1950, and Chief of Station Karlsruhe to Chief of Station Vienna, December 29, 1950, and January 8, 1951, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[36] Beissner, Willi, Egypt, April 4, 1952, and CS-7845, April 30, 1953, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[37] Pull 6790, IN 48795, February 19, 1957, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[38] From NEA-2, Hajj Amin al-Husayni, December 10, 1952, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 60, Haj Amin al-Husseini Name File, v. 5, f. 2.

[39] Report CS-7845, April 30, 1953, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[40] NECA-1153, To Chief NEA, November 27, 1953, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[41] Chief of Base, Munich to Chief of Station, Germany, February 17, 1958, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[42] D-819 Report, 66th CIC Group, and Andrew N. Havre to Commanding Officer, Region IV, 66th CIC Group, November 23, 1954; and Warren S. Leroy to Assistant Chief of Staff G-2, November 23, 1954, NARA, RG 319, IRR Beisner, Wilhelm XE 00819.

[43] IN-39568, March 6, 1958, DAMA, March 7, 1958, and 1961 chart of Beisner’s connections, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[44] Central Registry, 66th CIC Group, June 30, 1959, NARA, RG 319, IRR Deumling, Joachim, XE 017494.

[45] JX 5911, undated, and JX-6019, July 7, 1954, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 23, Joachim Deumling Name File.

[46] Mallmann and Cüppers, Nazi Palestine, p. 205.

[47] IN-48099, to Director Cairo, March 25, 1958, and OUT-72412, from Director, March 26 [?] 1958, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[48] See Christopher R. Browning, The Final Solution and the German Foreign Office (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1978), pp. 191–93.

[49] EGF-2517, November 12, 1957, NARA, RG 319, IRR Rademacher, Franz, XE 304625.

[50] Attachment to Hook Dispatch 1069, February 2, 1959, Willi Beissner, and EGMA 40944, March 9, 1959, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[51] Mallmann and Cüppers, Nazi Palestine, p. 205. Chief, Munich Liaison Base to Chief, EE, October 20, 1960, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[52] EGMA-52899, January 10, 1961, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[53] EGOA-14075, Chief of Station Germany to Chief, EE, April 3, 1961, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File. CIA ultimately concluded that the ambiguous first letter was an R. Alois Brunner used both pseudonyms and others besides.

[54] EGMA-54517, Chief, Munich Operations Group to Chief, EE, April 20, 1961; and EGOA-14451, Chief of Station, Germany to Chief EE, May 12, 1961, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 10, Friedrich Beissner Name File.

[55] Munich to Director, April 25, 1961, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 19, Alois Brunner Name File.

[56] Chief, Munich Operations Group to Chief, NE, May 10, 1961, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 19, Alois Brunner Name File.

[57] EGMA-58837, Chief Munich Liaison Base to Chief EE, May 21, 1962, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 103, Franz Rademacher Name File.

[58] Browning, The Final Solution and the German Foreign Office, pp. 196–201.

[59] See Breitman, et. al., U.S. Intelligence and the Nazis, pp. 160–64. The [Israeli] assassination attempt is mentioned in EGMA-58837, Chief Munich Liaison Base to Chief EE, May 21, 1962, NARA, RG 263, E ZZ-18, B 103, Franz Rademacher Name File.

RSS

RSS

Latest Comments

Hello Mike, Thank you for your positive feedback to the article. I felt there wasn’t too much critical analysis of ...

Thanks for this considered and well constructed article. A follow up article on the manner in which the editorial contro...

THE CLUELESSNESS OF CLAIMING THAT OBAMA'S MIDDLE EAST POLICIES WERE A FAILURE CANNOT BE FURTHER FROM THE TRUTH, WHAT THE...

As long as Obama is the president of the usa do not trust the us government......

Thank you for an good read....