![]()

Mon, June 13, 2011 | Turkey Analyst, vol. 4 no. 12 | By M. K. Kaya

A Divisive Campaign in a Polarized Turkey

This article was first published in the Turkey Analyst (www.turkeyanalyst.org), a biweekly publication of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center. © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center, 2010.

The June 12 general election was historic as it was the first general election in Turkey over which the shadow of the military and the other institutions of tutelage did not fall. Yet the ruling party’s tactics ensured that the election campaign still took place in an environment whose atmosphere was all but democratic. The elections underlined Turkey’s traditional split between a rightist majority and a leftist minority; it also showed that the AKP and the Kurdish BDP — the election’s main winner — both benefited from the polarized electoral environment; further, the main opposition CHP’s impossibly eclectic crop of candidates had too little of a common denominator to challenge the AKP. It will now be up to the new parliament to put the divisive campaign behind it and achieve a new constitution through compromise. Whether that is at all likely nevertheless remains doubtful.

Background

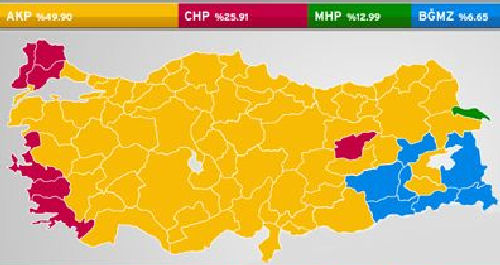

On Sunday, June 12, the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) received 49.9 percent of the votes; it will now have 326 seats in the 550-seat parliament. In the 2007 general election, the AKP secured a greater parliamentary representation — 341 seats — even though its share of the votes was lower, at 46.5 percent, than it was this year. Although the AKP increased its support by 3.4 points, its parliamentary group will number 15 less deputies. As the AKP gets fewer than 330 seats, it will not be able to unilaterally draft a constitution. However, that possibility should not be excluded out of hand; the AKP could still reach the required number of deputies if it tries and succeeds in transferring deputies from the other parties. That has happened before in Turkish politics.

The Republican People’s Party (CHP) received 25.9 percent of the votes. That result is a severe disappointment for the main opposition party, even though it represents an increase of nearly five points compared to its 2007 result, 20.8 percent, since it had expected to attain 30 percent of the votes. The CHP will nonetheless have increased its parliamentary representation from 112 to 135 deputies.

The Nationalist Action Party (MHP) managed to retain its place in parliament. It had been speculated that the MHP could fall below the ten percent threshold to parliament. That expectation led the AKP to adopt a Turkish nationalist discourse during the election campaign; the AKP calculated that it would thus attract MHP supporters. If the MHP had been denied parliamentary representation, the ruling party would have secured the necessary seats for unilaterally pushing through a new constitution. The MHP was also hurt by a series of sex scandals that led to the resignation of several leading party officials. The support for the party fell slightly, to 13 percent, and it will have 53 instead of 71 seats in the new parliament. Yet ultimately the tactic of the AKP backfired; instead of pushing the MHP below the threshold, it served to mobilize support for the MHP. As what the AKP was attempting to achieve became apparent, voters who were otherwise likely to cast their ballots for the CHP came to the rescue of the MHP.

Without doubt, the BDP (Peace and democracy party), which represents the Kurdish movement, was the most successful party of the election. The BDP, which fielded independent candidates in order to circumvent the nationwide ten percent threshold, succeeded in increasing its representation from 22 to 36 deputies. However, in terms of percentage of the vote, the success was much more modest: in 2007 the party (which was then named the Democratic Society Party) got 5 percent of the votes; on Sunday it share reached 6.6 percent. One explanation for the increased support is that the BDP, which has a leftist orientation, this time forged an alliance with other, conservative Kurdish forces. Conservatives like Şerafettin Elçi and Ahmet Tan have now been elected to parliament. The Kurdish alliance also includes prominent Turkish socialists like Sırrı Süreyya Önder and Ertuğrul Kürkçü, as well as a Christian Assyrian, Erol Dora, who was elected in the city of Mardin. His election represents a first in the history of Turkish democracy.

It must be noted that the June 12 elections were held under the shadow of mechanisms of government pressure that undermined the fairness of the electoral process. In an environment where large numbers of journalists were jailed for a variety of reasons and where media owners were slapped with billion-dollar fines, the media was unable to play the role it normally does in democratic elections. To illustrate the climate of the elections, a businessman who projected that the opposition CHP would be the largest party was publicly threatened by the Prime Minister of the risk he was taking.

Former main opposition leader Deniz Baykal was forced to resign as a result of a bedroom video released a few months ahead of the important constitutional referendum of September 2011. This time, the opposition Nationalist Movement Party was the target of this tactic. In the middle of the electoral campaign, sex videos involving ten of the fifteen members of the party’s board were released to the public. Instead of seeking to find the forces that orchestrated this sting operation, the ruling party brazenly used the revelations as ammunition in its electoral campaign. As many informed analysts have noted, it is unlikely that such a comprehensive sting operation could have occurred without the support of the country’s security structures. In this sense, the elections in which the AKP emerged as a winner occurred in a most undemocratic environment.

Implications

The 2011 general election did not alter the proportions of the traditional left-right divide in Turkey. For decades, the votes have been split 65-35, with the left usually receiving around 35 percent. This election saw a recurrence of that historic pattern: the total votes of the AKP and MHP — taken together with the two other parties of the right that failed to get over the ten percent threshold (the Felicity party, the Democrat Party and the HAS party) stand at 65 percent. Meanwhile, support for the CHP, BDP and the small leftist parties was the usual 35 percent.

What accounts for the increase in support for the AKP compared to its 2007 results is the erosion of support for the center-right DP. In 2007, the DP got 5.4 percent of the vote. On Sunday, that support all but evaporated, with the DP receiving a dismal 0.65 percent. This time, former DP supporters cast their ballots for the AKP, and in some western cities, for the CHP. Another party that was absent this year was the Turkish nationalist Young Party which received around 3 percent of the votes in 2007. Much of that vote accounts for the 5 point increase in the support for the CHP this year. For instance, the CHP was able to get a deputy elected from the city of Sakarya for the first time in 34 years; significantly, Sakarya was a stronghold of the Young Party back in 2007.

Compared to the 2007 general election, the CHP increased its support by almost 4 million voters. Obviously, that is a significant achievement from the party’s perspective. However, this election has once again demonstrated that the party fails to connect with voters across the whole of Turkey’s geography. Its support still remains largely confined to a few large cities along the western coastal rim. The AKP, on the other hand, also has a strong presence also in those areas where the CHP and the BDP are strongest; indeed, this year, the AKP succeeded with its ambition to increase its votes in the western coastal rim.

It is particularly noteworthy that support for the ruling party grew in the western city of Eskişehir; that city is a CHP stronghold, and its social democrat mayor is highly popular. The CHP was expecting an even better result in Eskisehir this year. Instead, the success of the AKP cost the CHP one deputy. That setback is explained by the fact that the CHP had nominated Süheyl Batum, one of the party’s deputy chairmen, who has made himself a name as an intransigent supporter of the old tutelage regime and of the suspects in the Ergenekon coup conspiracy trial. Apparently, that did not go down well with the more enlightened CHP electorate in Eskişehir.

Indeed, if anything, this election has made plain that the CHP’s “eclectic” tactic of making room for widely contradictory stances within the party works very poorly. Ergenekon suspects Mehmet Haberal and Mustafa Balbay did get elected to parliament, but it is not a wild guess to assume that their presence on the candidate lists also cost the CHP support. Notably, the CHP failed to make any inroads in the Kurdish southeast, even though the party had elected Sezgin Tanrıkulu, a prominent Kurdish figure, as deputy chairman. The contrast between Tankrıkulu’s liberal discourse and the die-hard kemalism of a Süheyl Batum is bound to have created significant confusion among the electorate: while the former puts off the traditional supporters of the CHP, the latter alienates the new voters that the party had been hoping to attract. It is safe to assume that this impossibly eclectic nature of the “new” CHP will be a source of severe internal tensions as the party evaluates the outcome of the election and attempts to chart a course for the future.

The MHP, although it managed to survive in parliament, is the clear loser of the election. The MHP has not been able to produce a political vision that goes beyond dogmatic opposition to any kind of liberalization in the Kurdish issue, and opposition to the EU. It can be expected that the future of the party leader Devlet Bahçeli and of the rest of the leadership will be subject to discussions in the days and weeks ahead.

The importance of the BDP’s electoral success cannot be overstated. The party is now in the position of being able to speak for a majority of the Kurdish electorate in the southeast. The balance of power has shifted dramatically to the Kurdish movement: In 2007, 45 of the 65 deputies from the largely Kurdish-populated provinces of Ağrı, Batman, Bingöl, Bitlis, Diyarbakır, Iğdır, Hakkari, Kars, Mardin, Muş, Şırnak, Urfa and Van went to the AKP, while the Kurdish DTP secured 19 deputies. This year, the number of AKP deputies from the region fell to 34, while the Kurdish BDP increased its representation to 31 deputies. The BDP also succeeded in having five deputies elected in Adana, Mersin and Istanbul, cities which have received a huge influx of Kurdish immigrants during the last decade.

Conclusions

As the 2011 general election has demonstrated, the Kurdish issue is going to set the tone of Turkish politics. As the new parliament now sets about to draft a new constitution, the Kurdish issue and its constitutional ramifications will occupy center stage.

The challenge that Turkey faces is indeed daunting: after a highly charged and polarizing election campaign — which came to be dominated by the AKP’s Turkish nationalist discourse and the BDP’s no less nationalistic and intransigent rhetoric — the parties will now have to surprise each other with generosity and restraint in order to reach a societal concord that defuses the escalating ethnic tensions.

M. K. Kaya is a contributing editor to the Turkey Analyst.

RSS

RSS

A Divisive Campaign in a Polarized #Turkey | #AKP #Islamism http://bit.ly/kZlhyq

A Divisive Campaign in a Polarized #Turkey http://t.co/4wKckSF

A Divisive Campaign in a Polarized #Turkey http://t.co/4wKckSF

A Divisive Campaign in a Polarized #Turkey | #AKP #Islamism http://bit.ly/kZlhyq