![]()

Wed, July 20, 2011 | By Alon Sheinberg

A Tainted Alliance: The Rise and Fall of American Influence in Iran

“The truth is incontrovertible, malice may attack it, ignorance may deride it, but in the end; there it is.” — Winston Churchill

The memory of centuries of foreign manipulation and interference is a constant factor in the foreign and domestic policy of modern Iran. The great game that Russia and Britain played for control over central Asia in the nineteenth century left scars on a generation of Iranian leaders and deeply installed a determination to insulate Iran against foreign influence. When America became a global power after World War II, Iranians for a brief moment saw the United States as a protector against Soviet and British infringements. But when the CIA masterminded a coup against a nationalist prime minister and reinstalled the shah on the Peacock throne, Iranians would in time restore their resentment over foreign manipulation.

The objective of this paper is to identify what it was about the Cold War that placed Iran, as Henry Kissinger stated, “at the vortex of history?”[1] The answer will be developed by examining the combination of events that pushed Iran and the United States into an alliance that eventually created intensely hostile anti-Americanism in Iran. The outline of this volume is as follows: Part one identifies the source of American involvement in Iran and the upheaval that laid the foundations for nearly three decades of American influence. Part two examines American interests in Iran through two important considerations: Competition with the Soviet Union in the Cold War and the economies of oil. Both were equally significant and the American desire for a strong oil rich partner in the Middle East led a series of US administrations largely to look the other way while oppression and corruption of the shah’s rule fed popular resentments that would ultimately lead to an explosion. The backlash was the Islamist revolution led by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1979 and the Iranian hostage crisis.

Part I

Historical Retrospective: The Roots of US Intervention

The site of the first confrontation between the Soviet Union and the Western powers was Iran whose strategic location had rendered it the object of Russian and British rivalry as early as the end of the nineteenth century. Prior to the First World War these two imperial powers had jointly partitioned the country into spheres of influence. For the British this proved a smart move since Winston Churchill’s decision, as First Lord of the British admiralty to convert the Royal Navy from coal burning to oil ships would require Iranian oil to fuel his new armada. However, in the case of Russia, the collapse of the Tsarist Empire and the advent of the Bolshevik regime had temporarily resulted in a reduction of influence in Iran. As a result, Great Britain proceeded to organize and supervise the exploitation of the vast reserves of petroleum that had recently been discovered while striving to establish predominant political influence on the government in Tehran.

Dissatisfaction with Iran’s postwar government especially among nationalists, along with the absence of any strong national party, made it possible for Cossack commander Reza Kahn to overthrow the Sepahdar government and seize power with force in a coup d’état in 1921.[2] Four years later he was proclaimed the shah. A nationalist politician named Mohammed Mossadeq was one of the four members of the Iranian parliament, the Majlis, who opposed him. Mossadeq perceived the root cause of the Iranian malaise to be the British interference in Iranian affairs that led to the coup d’état for the primary purpose of aiding the British oil interests through the now called Anglo-Iranian oil company, which the British owned 51%.[3] The Majlis soon discovered that the British oil giant, Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, systematically cheated their government of billions and hatred of the British, escalated by fear of the Soviets ran so high, that in the 1930’s Nazi influence began to be felt in the region.

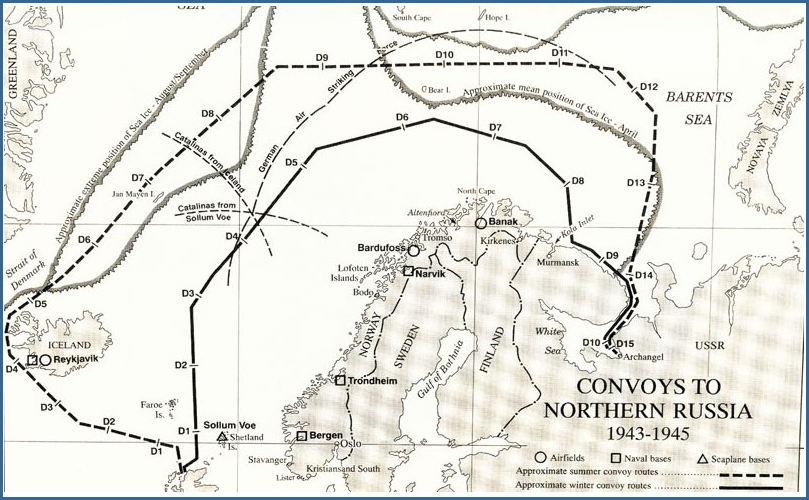

At the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, Americans having barely survived the Great Depression viewed the Middle East as the last place in which they would confer their attention.[4] However, matters changed in June 1941, when three German army groups invaded the USSR, one of which, Army Group South under field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, headed for the Trans caucus region in south-western Russia, toward the Caspian and Iran. The British and the Soviets suddenly allies immediately insisted that Iran expel all German nationals of whom there were some three thousand, among them intelligence agents who had been establishing underground networks in the country.[5] The Iranian monarch, Reza shah refused. Complicating matters, the vital Trans European lines of transport and communication to the USSR were severed by the German advance and there remained only two avenues of supply by which vital us Lend Lease and other materials could reach the Soviets: the treacherous Murmansk round for ship convoys (see figure 1.1), and the trans-Iranian railroad from the Persian Gulf to the Soviet border in north-western Iran. The solution was an Anglo-Russian invasion.

On 25 August, 1941, Iranians woke to leaflets fluttering down on the city streets, announcing the Anglo-Soviet invasion: “Iranians! There are thousands of Germans on your soil; according to important plans they hold key positions in your industry and they are only waiting for one word from Hitler to disrupt you principle source of wealth (oil)…We have decided that the Germans must go and if Iranian will not deport them then the English and the Russian will and our forces will not welcome resistance. Iranians! We have no quarrel with you nor designs upon your nation nor upon your property or you lives, we only want to expel the accursed Germans…”[6] The Anglo-Russian invasion brought forth a shift in Iran’s policy of neutrality in favour of a defensive alliance with the Soviet Union and Britain while forcing Reza shah into exile on the island of Meritorious. A more compliant government nominally headed by his young son Reza shah Pahlavi was installed.

This dramatic change in the international environment had an unseen ramification in that it directly involved American troops on Iranian soil. Britain’s forces were spread too thinly around the world and in response to London’s request, Washington sent 30 000 American troops committed to support the occupation in south-western Iran while providing logistical support and transport using its airports and roads to deliver roughly $18 billion worth of military aid to Stalin.[7] In the 1942 Tripartite Pact, the three allies guaranteed Iran’s territorial sovereignty and independence by agreeing to withdraw their troops from Iran no later than six months after the end of the war.[8] However, shortly after the war a crisis emerged and America would remain in Iran; principally as a counterweight to the Soviet Union and only secondarily to Britain.

The crisis that unfolded shortly after the end of World War II took shape when the communist controlled Tudeh party supported a separatist revolt in the north-western province of Azerbaijan, bordering on the Soviet Union. The Russian occupation army prevented the Iranian government from supressing the insurgency by denying its military forces access to the rebellious province. Shortly after, a provincial assembly dominated by the Tudeh party was elected in Azerbaijan and promptly declared its autonomy, a move that was widely regarded as the first step toward the absorption of the province by the Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan across the border.[9] Further, The Iranian prime minister received a set of demands from Moscow, which included indefinite retention of Soviet troops in northern Iran, recognition of the autonomy of Azerbaijan and the formation of a Russian Iranian joint stock company to exploit petroleum reserves in the northern part of the country. Interpreting these Soviet moves as the beginning of a campaign to obtain effective control of the entire country, including its rich petroleum reserves and its ports on the Persian Gulf, the British and American governments applied vigorous diplomatic pressure on the Kremlin to terminate its Iranian adventure. Washington’s determination to bolster Pahlavi regime set the stage for the establishment of an intimate security link between Washington and Tehran that was to last for a quarter of a century.

Toppling Mossadeq

In Iran, another crisis brewing was an internal one as Mossadeq called upon the Majlis to renegotiate the British oil concession. The British took twice as much income from the oil as Iranians and now Iran demanded a fifty-fifty split. The British refused and tried to sway opinion by paying politicians, newspapers editors and the state radio directors, among others. Unknowingly the British were courting a disaster and it came in April 1951, when the Majlis cited to nationalize Iran’s oil production and within a few days Mossadeq became Prime Minster. In Britain, the seventy six year old Churchill returned to power as Prime Minister and in an effort to destroy Mossadeq, Churchill sent British warships off the coast of Iran, solidified an international boycott of Iran’s oil, and even ordered British commanders to draw up plans involving 70 000 troops seizing Iran’s oil fields and the Abadan refinery. Mossadeq, who was 69 at the time, took his case to the United Nations and the White house and claimed that during the half century of the former companies domination of Iran’s oil, it has never been possible for the Iranian government to make a free decision in its internal affairs and its foreign policy.[10] On a more frightening note he warned Harry Truman in private that a British attack could set off World War III. Truman told Churchill flatly the United States would never back such an invasion and Churchill countered in that the price for British military support in Korea Was American political support for his position in Iran. They reached an impasse in the summer of 1952.

The British had decided to take action and in November of 1952 they were caught red handed trying to topple Mossadeq’s regime. Mossadeq responded by expelling the British embassy and threatening America with Russian hegemony. The instability of the region created a fragile situation for the United States in that Iran may fall to the Soviets. In a 1953 National Security Council meeting, Secretary of State Allen Dulles amplified such consequences stating that if Iran went communist all the dominoes in the Middle East would fall; 60% of the free world’s oil would be in Moscow’s hands depleting the Americans reserves for war; and, oil and gasoline would have to be rationed in the United States.[11] Truman was not convinced and thought to provide Iran with more loans. However, the Eisenhower administration which seemed fascinated with covert actions and which viewed Mossadeq as semi invalid who carried out a fanatical campaign, joined the British in seeking the ousting of Mossadeq as Operation Ajax commenced in 1953.

While the United States stated their foreign policy was to support Mossadeq, the CIA set out to depose him. In case the need arouse to fight off a Soviet invasion in Iran or the Tudeh, the small yet influential outlawed communist party of Iran, the CIA already had enough cash and guns stashed away to support ten thousand tribal warriors for six months.[12] All that was needed was to shift the target and aim to undermine support for Mossadeq inside Iran’s mainstream political and religious parties. The CIA did not have British decades of experience in Iran, nor nearly as many recruited Iranian agents, but it had more money to hand out; at least $1 million a year, considered a great fortune in one of the world’s poorer nations. A campaign of bribery and subversion was stepped up as agency officers and their Iranian agents rented the allegiance of political hacks, holy men to denounce Mossadeq from the mosques, and thugs to break up Tudeh rallies with their bare knuckles. On August 19, 1953, buses and trucks filled with hired mobs, rented soldiers and tribesman from the south arrived at the capital and demonstrations began. The mobs shouted anti Mossadeq, pro shah slogans and proceeded to march through the streets. As momentum gained, many joined them and they seized ranking members of the government, burned four newspapers offices and sacked the political headquarter of the pro Mossadeq party.[13] The CIA had created a degree of violence sufficient to stage a coup and reinstall Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Where Mossadeq sought a path of nonalignment, the shah saw Iran’s interest in alliance with the West. Eisenhower viewed the shah as one who has always impressed and as a man of good intent. After being reinstalled to the throne, he rigged the next parliamentary elections, imposed three years of martial law while launching a massive crackdown in which 2000 were arrested by the end of 1953.[14] He called upon the agency and the American military mission in Iran to help him secure his power by creating a new intelligence service, SAVAK serving both the interests of the United States as its eyes and ears against the Soviets and the shah’s who wanted a secret police to protect his power. In the decades to come tens of thousands were tortured by SAVAK and at least thousands were murdered.[15] The coup was regarded as a great triumph and a national victory which changed the course of an entire country. However, Iranians who had a history of being victims of foreign subversion would not forget this one incontrovertible fact; the United State did overthrow Mossadeq and a generation of Iranians grew up knowing that the CIA had installed the shah. In time, this fact would return to haunt the United States.

Part II

1953-1963: Conditional Support and Cold War Politics

After the 1953 coup, the United States became the dominant foreign power in Iran. The single most influential systemic factor that characterized the Iranian-American alliance was a mutually perceived Soviet threat. Iran under the shah commenced an extensive modernization program while adopting a staunchly pro-west political posture. Due to the unusually personal nature of the relationship between the shah and the United States government, the two countries not surprisingly came to share similar views on the regions security requirements resulting in increased American assistance. Prior to the toppling of Mossadeq, to avoid any temptation to align with the Soviets, Iran was given economic and American military assistance primarily of a technical type, and rarely included American military equipment. However, after reinstalling the shah the United States increased the amount and type of military aid Iran received. Between 1949 and the rise of Mossadeq to power Iran received only some $16 million whereas between 1953 and 1961 it acquired $430 million.[16]

Among the signs of the shah’s pro-western orientation was Iran’s joining the Baghdad Pact in October 1955, with the other “Northern Tier” countries including Iraq, Turkey, Pakistan, and Great Britain. The pact was considered a hostile alliance both by Nasser’s Egypt and by the Soviets, who began to beam hostile broadcasts in Persian into Iran.[17] Due to its inability to normalize relations with the Soviet Union in the north and radical Arab subversion in the south, the shah developed a fixated fear of a pincer movement. Adding to tensions with the Soviets was its rapprochement to the 1958 Iraq Revolution, which Iran viewed as out of tune with the Soviet Union’s own expanding economic ties and good neighbourly relations. The Iraq Revolution also had both domestic and regional consequences: Domestically the destruction of the monarchy in neighbouring Iraq could provide an example to Iranian opponents of the Shahs regime and the Kurdish problem could combine with other tribal discontents erupt into a general tribal rebellion; Regionally, it further intensified Iran’s conflict with Egypt and Syria. The extent of this conflict was seen in 1960 after replying to a foreign correspondent whether Iran recognized Israel; the shah stated the country had recognized Israel long ago. Egyptian President Nasser denounced the shah.[18]

In the Cold War atmosphere of the 1950’s the United States government was concerned mainly that Iran remains anti-communist and anti-Soviet. While the shah emphasized military security, the United States placed its aid priority with the emphasis on the need for basic socioeconomic development. Iran was in a dire situation and needed a credible deterrent. The American defense agreement of 1959 did little to assuage Iranian dissatisfaction. Although it formally and bilaterally committed the United States to the defense of Iran, it failed to go beyond existing American commitment under the Eisenhower doctrine, which provided for consultation of defense against Soviet and other aggression if controlled by international communism. The shah attempted countermeasures such as a non-aggression pact and negotiating arms acquisition with the Soviets in 1958-59 which both failed, as well as seeking a new sought friendship with King Saud and President Chamouni of Lebanon in an attempt to form a bloc of moderate pro-western states and thereby balance the power in the region.

With the move toward United States détente with the Soviet Union and war not being considered imminent, in the 1960s Iran’s policy to the United States was one of continued disappointment inherited from the 1950s. This was increasingly seen in during the Kennedy administration in 1961-63, which deemed it more important to American strategic and economic interests in the area to have an Iranian government with a broader internal base, greater efficiency and popularity, and less corruption than existed in the 1950’s. Consequently, the shah was asked to deal with corruption and inefficiency, and the Unites States loans and grants decreased. In 1962 the US ended its annual payments of $30 million budgetary supports, and later that year Lynden Johnson paid a two day good will visit to Iran.[19]

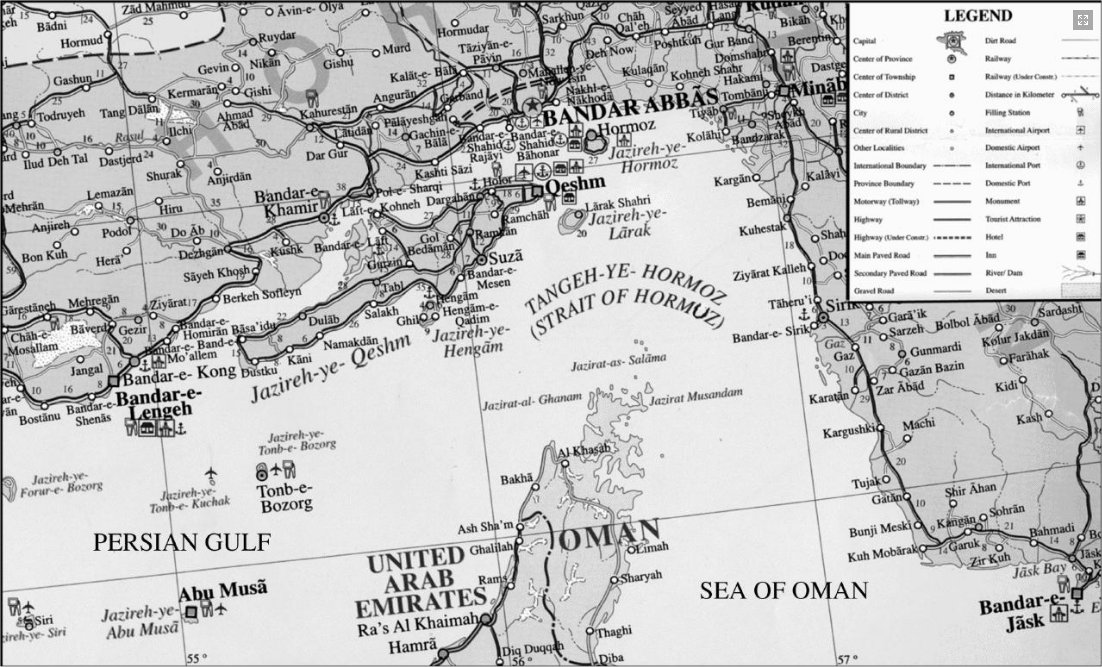

1963-1979 Unconditional Support and Iran’s New Oil Wealth

For the United States, concern with détente was as significant a source of foreign policy as the pincer movement was for Iran. If at first the United States wanted to provide aid emphasized on socioeconomic developments in keeping Iran West, as time passed Iran took on an increasing importance as the guarantor of security for the Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz (see figure 1.2). Both Washington and the shah shared the common goals to protect the safety of the shahs regime against internal subversion sponsored indirectly either by radial Arab regimes of Soviet Union; to protect Iranian oil resources and the vast oil installation concentrated in the Gulf area against deliberate or accidental disruption from any quarter; and, to preserve freedom of navigation in the Persian Gulf and particularly the strait of Hormuz, where by the mid 1960’s some twenty five million barrels of Iranian oil was transported largely to the industrialized economies of America, Europe and Japan.[20]

In the late 1960’s to the early 1970’s America increased support for the shah came as a result of Cold War politics manifesting itself via: the power vacuum created by the British decision to withdraw the Persian Gulf in 1968 and the American reluctance to pick up its role; the potential threat posed by Soviet activity in the Gulf area; the need to bold up a moderate pro-Western regimes in the area to offset radical Arab regimes as seen earlier with the United Arab Republic and the formalization of Iraqi alignment with the Soviet Union in the Soviet Iraq treaty 1972. The shah stressed his determination to strengthen Iran’s defensive capabilities in a way that would discourage any potential aggressor while also serving as a factor of peace and stability in the Persian Gulf. This suited the Nixon doctrine which stipulated that the United States would lean on regional proxies to defend themselves and their neighbours, maintain stability and ensure that American interests were looked after while the United States concentrated on the Soviets. After the British pull-out from the gulf, the West was happy to see Iran had in fact become the gendarme of the area, fighting leftist led rebels in Oman’s Dhofar province and threatening other potential disturbers of the status quo.[21] It seemed Iran bore the primary responsibility of the Persian Gulf and the Nixon administration who underwrote the shah as the policeman of the Gulf agreed to sell him whatever non-nuclear arms he wished. In a statement about the shah Richard Nixon stated; “I just wish there were a few more leaders around the world with his foresight.”[22]

Iranian Oil

One major consequence of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War was an Arab boycott on western suppliers of Israel. With increasing indications that the Arab states might use the oil weapon in order to bring about changes in American policy, the shah pushed successfully for a redoubling of oil prices. While the American press and government officials began to criticize the shah for pioneering the OPEC price rise, major American business interests became more closely tied to and even dependant on the shah’s regime. This was especially true for the armaments business sector which was eager to sell billions of military equipment to Iran to reinforce the economic drain caused by the OPEC price rise. The shah had implemented an effective military build-up; yet, it was hard for many to give him credit for any achievements when so much more could have been done with his oil billions. For example, oil revenues stood at $885 million in 1971 climbed to $17.8 billion in 1975.[23] Yet, instead of the shah investing his oil billions in the urgently needed socioeconomic infrastructure, the same year he signed ridiculous acquisitions such as an arms deal for $10 billion in American arms, including 300 F-16 and 200 F-18 fighters which were still under development at the time and would take a decade just to train Iranian pilots to handle so many ultramodern aircraft.[24]

Ironically, the shah in part was undone by his OPEC triumph and its consequences within Iran. The process involved a stress on big industry and agriculture and the stress on big and complex projects increased. Since there had never been any adequate program of technical education there were not enough Iranians for skilled and technical jobs, much less scientific or managerial ones. Hence the importance of foreigners grew as over rapid migration contributed to the over-crowding, housing shortages, inflation, income distribution inequities and overall anti-American feeling.[25] Given the western business interests in Iran and the Anglo American desire to use Iran strategically in the gulf against Russia and against possible trouble with bordering Muslim countries, it is no surprise that United States predominantly went along with the shahs reported desire that they not contact the opposition, and with rosy assessments that the opposition consisted of small and unimportant groups of Marxist and religious fanatics. American government and business interests thus preferred the shah to any popular alternative, which would have had to reduce American economic and political influence and might alter Iran’s pro American foreign policy.[26]

The association of the shah’s regime with western culture, commodities and vices brought on traditionalist reaction even among many former westernizers, which took an Islamic form. Western values did not trickle down to the popular classes any more than did significant benefits from the modernization program. The suppression or co-optation of much of the opposition over the years, including its leftist and its more liberal or moderate elements, along with the growing gap between the masses and elite, made it increasingly likely that eventual effective opposition would come from those who could appeal to the traditional disaffected masses more than from westernized liberals or leftist. Ultimately the vast majority of Iranians became more anti-western, more anti shah and more open to oppositionists who stood against the shah, the west, and western ideas.[27]

The shah was running a virtual dictatorship, while Carter was calling the monarch, “an island of stability in a sea of turmoil.”[28] The Americans were not blind to the events in Tehran, but the Carter administration did not have a great deal of experience with Iran and was preoccupied in the delicate state of the negotiations of the Camp David Peace talks and the SALT II treaty with the Soviets.[29] Perhaps the greatest neglect was the fact that Iran was always a religious country and Iranians clung to Islam and saw in it a source of strength and guidance well beyond what became the norm in many other nations. On February 1, 1979 followers of a seventy seven year old religious zealot, pushed the shah from the Peacock throne through a popular revolution and Ayatollah Khomeini became supreme leader of the country. The idea that religion would prove to be a compelling political force in the late twentieth century was incomprehensible. Few believed that any ancient cleric could seize power and proclaim Iran an Islamic republic. In November 1979, a group of Iranian students, all followers of the Ayatollah seized the American embassy and held the fifty three hostages for the rest of the Carter Administration, 444 days and nights. Freed at consent of their captors at the hour that president Carter left the White House for the last time, the hostage taking proved to be a political statement devised to humiliate the United States and an act of vengeance for the 1953 coup in Iran. The zeal of the Iranian revolution would haunt the next five presidents of the United States and kill hundreds of Americans in the Middle East.

Conclusion

In returning to the question of what it was about the Cold War that placed Iran at the “vortex of history,” the conventional wisdom that holds simply that it was oil is not entirely correct. While oil was indeed a small part of the American calculus, the far better answer is geography. Situated between the Communist Soviet Union and the oil rich Persian Gulf, Iran became strategically vital to the United States. As the Cold War developed, a generation of American leaders came to view Stalin’s Soviet empire as an opponent to be challenged at every turn. Consequently, the United States acted to prevent the spread of Soviet influence into the Middle East and to protect access to Middle East oil.[30] As it happened, one conflict point was Iran and the consequence was the clandestine formation of the American-Iranian alliance.

Beginning in the 1950’s and increasingly in the next two decades the shah who was reinstalled courtesy of the United States, showed a growing interest in modernizing Iran’s economy and society, and making the country Western in character and militarily strong. He followed his father’s precedent, but whereas Reza shah, with fewer economic resources and much lower oil income had minimized economic dependence on the West in his modernization program, Mohammad Reza greatly increased it. The result was that for the next twenty five years, the United States was deeply involved in all aspects of Iranian development as Iran transformed into a major asset during the Cold War. In return, the American-Iranian alliance had allowed the economically backward and military destitute Iran of the 1940s to rise to the chief power in the Persian Gulf and an active member of the international community of nations.

The shah did share many of America’s general goals in the region: he sought stability; he opposed Nasser and other Arab radicals; he supported the state of Israel; he opposed Communism and the Soviet Union; and, he sought to prop up many of the other conservative monarchies in the region. But there were also important difference between Iran and the United States, and the combination of America’s unconditional support and Iran’s new oil wealth caused the shah to see off in directions that both the Nixon and Carter administrations had not anticipated. In retrospect, the United States decision to ally itself with the traditions of British colonialism in the Middle East would prove to be an historical mistake and a long term disaster for American and Western interests. At times the shah’s friendship paid off, but the tainted alliance came to an end and would be swept away by bitter anti-Americanism. For Iran, the memory of their alliance with the United States follows suit to their historical pattern of harmful foreign intervention, exploitation and manipulation. For the United States, the alliance with Iran serves as a memory of American power seeming unable to protect American interests which culminated in the long ordeal when Americans were held hostage in Iran.

Alon Sheinberg is a Research Analyst in the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) in Israel.

Notes:

[1] Treverton, Gregory F. Covert Actions: The CIA and American Intervention in the Post-war World. London: I.B. Tauris, 1987. Pg. 49.

[2] Keddie, Nikki R. Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution. Yale University Press, 2003. Pg. 81

[3] Weiner, Tim. Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA. Published by Doubleday, U.S.A. 2007. Pg. 84.

[4] Goode, James F. The United States and Iran: In the Shadow of Mussadiq. Macmillan Press LTD, 1997. Pg. 9.

[5] Daugherty, William J. In the Shadow of the Ayatollah: A CIA Hostage in Iran. Naval Institute Press. Annapolis, Maryland, 2001. Pg. 21.

[6] Goode, James. Pg. 10.

[7] Pollack, Kenneth M. The Persian Puzzle: The Conflict between Iran and America. Random House Publishing Group, 2004. Pg. 40.

[8] Ibid. Pg. 41

[9] Keylor, William. The Twentieth Century World: An International History. In Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press. New York, 2001. Pg. 225.

[10] Ruohallah, Ramazani K. Iran’s Foreign Policy 1941-1973: A Study of Foreign Policy in Modernizing Nation. University Press of Virginia, 1975. Pg. 439.

[11] Wiener Tim. Pg. 84.

[12] Ibid. Pg. 84-89.

[13] Ibid. Pg. 90.

[14] Pollack, Kenneth M. Pg. 73.

[15] Ibid. Pg. 139.

[16] Ruohallah, Ramazani K. Pg. 359-361

[17] Ibid. Pg. 139.

[18] Ibid. Pg. 404.

[19] Ibid. Pg. 359

[20] Ibid. Pg. 361-364.

[21] Keddie, Nikki R. Pg. 163-164.

[22] Wiener, Tim. Pg. 369.

[23] Pollack, Kenneth M. Pg. 108

[24] Ibid. Pg. 108-109

[25] Keddie, Nikki R. Pg. 164

[26] Ibid. Pg. 165.

[27] Ibid. Pg. 135.

[28] Wiener, Tim. Pg. 369.

[29] Pollack, Kenneth M. Pg. 131.

[30] Quandt, William B. American and the Middle East: A Fifty Year Overview. Brookings Inst. Press, 1993. Pg. 59.

Works Cited

— Daugherty, William J. In the Shadow of the Ayatollah: A CIA Hostage in Iran. Naval Institute Press. Annapolis, Maryland, 2001.

— Goode, James F. The United States and Iran: In the Shadow of Mussadiq. Macmillan Press LTD, 1997.

— Keddie, Nikki R. Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution. Yale University Press, 2003.

— Keylor, William. The Twentieth Century World: An International History. In Fourth Edition Oxford University Press. New York, 2001.

— Pollack, Kenneth M. The Persian Puzzle: The Conflict between Iran and America. Random House Publishing Group, 2004.

— Quandt, William B. American and the Middle East: A Fifty Year Overview. Brookings Inst. Press, 1993.

— Ruohallah, Ramazani K. Iran’s Foreign Policy 1941-1973: A Study of Foreign Policy in Modernizing Nations. University Press of Virginia, 1975.

— Treverton, Gregory F. Covert Actions: The CIA and American Intervention in the Post-war World. London: I.B. Tauris, 1987.

— Weiner, Tim. Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA. Published by Doubleday, U.S.A. 2007.

RSS

RSS

A Tainted Alliance: The Rise and Fall of #American Influence in #Iran | #tcot #Israel #Britain #Russia http://bit.ly/pZJSl8

A Tainted Alliance: The Rise and Fall of #American Influence in #Iran | #tcot #Israel #Britain #Russia http://bit.ly/pZJSl8

A Tainted Alliance: The Rise and Fall of #American Influence in #Iran | #tcot #Israel #Britain #Russia http://bit.ly/pZJSl8

A Tainted Alliance: The Rise and Fall of American Influence in Iran http://t.co/DmBs92A via @AddToAny