![]()

Saturday, January 10, 2015 | By R. Joseph Hoffmann

This article was first published in The New Oxonian under the title “Charlie and Ahmed”. It is reprinted here with permission by the author.

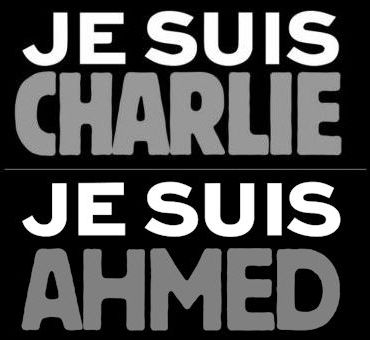

‘Je suis Charlie’ (I am Charlie). the slogan for free speech first used after the 7 January 2015 Islamic terror attacks in which 12 people were killed at the offices of the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo in Paris, France. Police officer Ahmed Merabet, who was patrolling the area at the time, was killed outside the offices. At his funeral, people used the slogan ‘Je suis Ahmed’ (I am Ahmed).

A friend writes in response to my last post on the topic of radical Islam that her Muslim friends and neighbours in Oxford are nothing like the Islamists she sees on TV. They are peaceful, law-abiding and upright citizens of the Realm.

Of course that is true. Mrs Saleem is a lovely woman and her son, Ahmed, a bright eyed and promising boy who enters middle school next year. What could be more obvious than that to lump her together with the most toxic examples of the faith she professes is a malignant thing to do.

We have been pounded in recent days to remember that our fight is not with Islam but with terrorism in the broad sense. That is also true — but to a lesser extent, and I will expect to be pounded for saying it — again.

After 9-11 (while members of the bin Laden family scuttled home from California to KSA) a number of pundits remarked that a war on “terror” or “terrorism” is nonsensical. George Soros called the phrase a “false metaphor.” Linguist George Lakoff argued that there cannot literally be a war on terror, since terror is an abstract noun. “Terror cannot be destroyed by weapons or signing a peace treaty. A war on terror has no end.”

Yet it seemed preferable to fight what could never be won than to taunt the dogs of war and agitate 1.6 billion Muslims, some of whom were dancing jigs on 9-11, with the possibility that the clash of civilizations was now officially underway.

Unfortunately, the war against “terror” or “radical Islam” (which the radicals will call simply “the true faith” الإسلام الحقيقي) or al-Qaida and its “affiliates,” and trainee decapitators worldwide, is not possible to conceptualize without Islam. That is the real point.

And that is the real problem. The violence we see in the Middle East, in Pakistan, in northern Africa, in Malaysia and Indonesia in not disincarnate or unattributable. Without the textual, educational and social context of Islam in those parts of the world — but perhaps in export form now also in parts of Europe — the current situation is unimaginable.

It is not a question of whether your Pakistani neighbor pays the milkman or likes a good chaw by the garden fence when she’s taking her clothes in. The problem with quantifying anything is that it can cut you on the back-swing: If statistically it could be shown that 75% of Muslims were supporters of violent jihad or Islamic State, would that make the problem more or less Islamic? Would it make the agenda of the jihadists more or less deplorable? To acknowledge the connection between Islam and violence is not the same as saying all Muslims are violent, or that Islam is inherently a violent religion. But accepting the connection, it seems to me, is the first step in putting the bait’ Ullah — the house of God — back in order.

Religion is a system of beliefs, practices, and ethics that develops within particular historical contexts. The fact that we all live co-incidentally in 2015 does not mean that those beliefs, practices, and ethics are the same. It does not mean that we share all aspects of belief or the same history or that beliefs have developed on parallel lines. They haven’t. Islam seems to know this better than liberal Christianity and secularized Judaism.

Religion helps to shape culture, but culture shapes religion in dynamic ways that are still not fully understood. There are organic connections and similarities between Judaism and Christianity, and between those faiths and Islam. But the cultural forces which have shaped these religions were markedly different, and the outcomes of their individual histories and interaction over time has also led to different results. It has made them more different than alike. How strongly you believe in God, or else how much of the history of the gods you know, will shape your response to the statement “We all believe in the same God.” But for someone like me, whose job it is to study religion in social context, the statement is false.

It is one of the nostrums of our time to say that all religions are alike. This belief — which is absurd and even ignorant — is positive for the three Abrahamic faiths if what we are saying is that they teach the same lovely truth about God and human conduct. In the mouths of skeptics and atheists on the other hand, as witness the work of the “new atheists,” it means it is a waste of time trying to distinguish the good and the bad in religion because, fundamentally, all religion is bad — or to use Christopher Hitchens’s phrase, poisonous.

I am a skeptic of long standing about “interfaith dialogue” because it relies too much on the first position (religions are just different paths to same shining truth) and almost totally ignores the second (religions mess you up).

Interfaith dialogue — which gives us the principle that our fight is with terror not with a religion — is the product of the self-help, everything is beautiful-era in which history and hard reality were tossed out the window leaving only the heady aroma of incense and flowers behind.

But if religious extremism has taught us anything, it has taught us that everything is not beautiful — that some people’s image of God is not just deficient but repugnant, and that most of the people who have this image and act on it are Muslims. That aroma you smell? It’s Aleppo and a girls’ school in the Sindh, burning, the sizzling remains of a suicide bomber who has just chanted Allahu akbar! That is the world we live in and these are the images that suffuse our view.

Christians don’t own the image of a God of love, mercy, justice and peace. There is no reason that cannot be a description of Allah — indeed, Mrs Saleem probably thinks it is. She has memorized all of the 99 beautiful names of God and can recite them on cue. But what needs to happen is that the god who seems to be passing for God, the god who commands people to kill fellow believers and murder children in their desks — that god must be denounced as a demon. Only within Islam can this transformation take place. It cannot be imposed through battles: there is no religious outcome to a battle.

That your neighbor is a law-abiding woman, a generous woman — a good mother and a good cook, and that all of her friends are like her — is a noble thing. But that she belongs to a religion that has a problematical position towards western democratic ideals such as free speech, freedom of choice to marry, the right of women to seek and obtain education, or travel freely without permission — is also undeniable.

For the last three hundred years revolutions have been fought in the West to ensure the separation of church and state, the supremacy of law over passion, and the basic freedoms of the individual — both men and women. By and large, the Church and the synagogue have followed along with this secular interpretation of our social existence In significant ways, they brought it about. But it is much harder for Islam to follow along happily, because it has not yet navigated the waters of secularization and sees its death at the end of the process.

Let me return to my original assertion: The fact that we all happen to occupy the same space in 2015 does not means that our values are the same. It’s well known by now that the children of immigrants tend to remember what their parents tried to forget, or ignore.

Thousands of Muslims who came to Europe for a better economic future, or to escape political chaos in their own country, found a culture that was hostile, condescending, or indifferent. That is why hundreds of younger Muslims are returning to the Islamic “state” to fight for the freedom they have come to believe has been stolen from them. After all, didn’t the West steal their homeland? Put its filthy boots on the ground all over the holy places? Create false hopes in the minds of their fathers, and then fail to deliver on the promise of jobs and the pursuit of happiness? Impose their language, values, technology, sexual habits — like so much opium — and then expect them to live without it? They find it difficult to feel patriotic about a country in which they seem doomed to perpetual negritude and second class status. Not all feel this way, but many do and some of the ones who do are simply too polite to say they do.

The West does not understand them. But is equally true to say that except for the jeans they wear, the rap they rap, and the iPhones they carry, they do not really understand the West. Islam as it taught and practiced is a pervasive source of that misunderstanding.

It is not some sort of intrinsic desire to kill that makes them violent. It is a sort of pornographic idealism, supported by the worst possible reading of an ancient book, interpreted by the worst possible religious experts — many of them in their twenties and lacking any sort of educational qualifications to teach or preach fiqh.

We do Islam no favour by not asking it to take its share of the blame. We do it a distinct disservice by spreading the veil of the sacred, the untouchable, around it-closeting it off from critique, satire and serious discussion through the imposition of blasphemy and anti-defamation laws.

When Muhammad marched into Makkah with his band of believers the Kaaba was used as a shrine for pagan idols, especially al-Lat, al-Uzza, and Manat, known together as al-Gharaniq (Daughters of God), and Hubal, a marriage god. He destroyed the idols in the sight of the crowds and rededicated it to Allah, since according to tradition it has been created in the time of Abraham and Ismail.

What Islam desperately needs is the radical energy to cleanse itself again. And that will take sufficient numbers of Muslims who are willing to see the men of violence as apostates and idol-worshipers, and dedicate themselves to wisdom and restraint.

Otherwise, Ahmed will find himself at eighteen dead on a foreign battlefield and not at Cambridge preparing to be a surgeon.

R. Joseph Hoffmann is a historian of religion and currently Professor of History (Middle Eastern Studies) at the American University of Central Asia. He graduated from Harvard Divinity School and the University of Oxford (DPhil, 1982). He teached among others at the University of Michigan, Westminster College (Oxford), California State University (Sacramento), American University of Beirut, Wells College and the New England Conservatory in Boston. He has held visiting positions at universities in Africa (Malawi, Zimbabwe, and Botswana), the Middle East, the Pacific (Australia and Papua New Guinea) and South Asia, most recently as Visiting Professor of History at LUMS in Lahore, Pakistan. His most recent books include an edited volume entitled Just War and Jihad: Violence in Judaism, Christianity and Islam (2006) and Sources of the Jesus Tradition (2010).

RSS

RSS

Latest Comments

Hello Mike, Thank you for your positive feedback to the article. I felt there wasn’t too much critical analysis of ...

Thanks for this considered and well constructed article. A follow up article on the manner in which the editorial contro...

THE CLUELESSNESS OF CLAIMING THAT OBAMA'S MIDDLE EAST POLICIES WERE A FAILURE CANNOT BE FURTHER FROM THE TRUTH, WHAT THE...

As long as Obama is the president of the usa do not trust the us government......

Thank you for an good read....