![]()

Tuesday, January 12, 2016 | by R. Joseph Hoffmann | American University of Central Asia

Transactional Implications of the God-Concept in Islam

This article is the nucleus of a manuscript by R. Joseph Hoffmann which will be published by Prometheus Books later this year. Due to its length, it’s printed here in three parts. You can read part 1 here and part 3 here. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of CrethiPlethi.com.

The God Concept

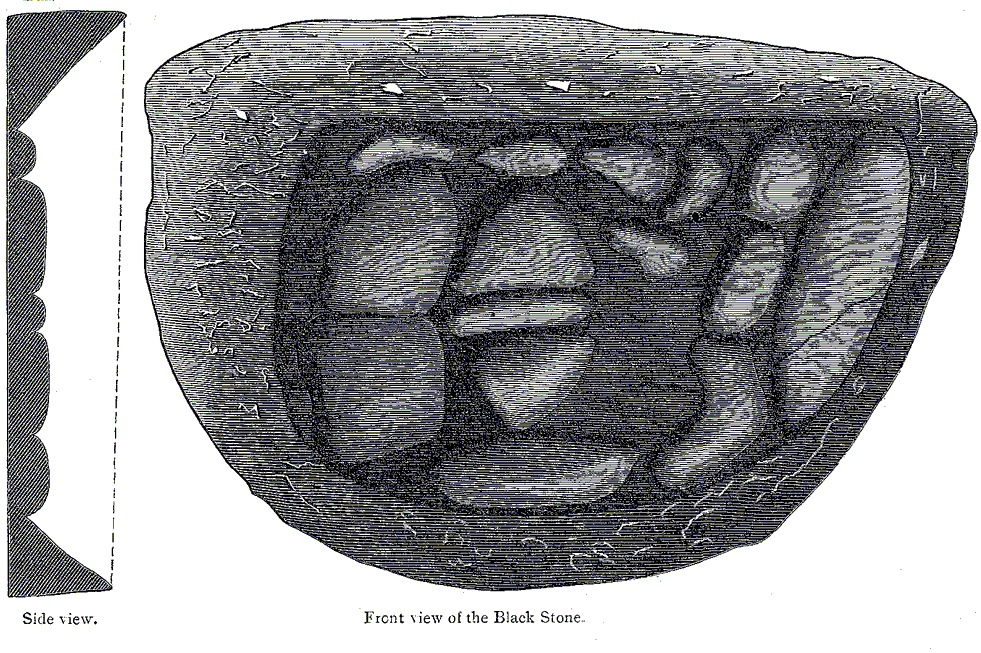

“Black Stone front and side” by William Muir (died 1905) – p.29 of the book “The Life of Muḥammad”. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

Islam arises as a desert cult opposed to the dystheism of a confederation of merchant-traders in the financial axis of Mecca. Mecca itself was no more than a pagan shrine (the Kaaba) and a tribal oasis; it was also a center of religious tale-swapping among the tribes,[14] lacking any semblance of the theological-intellectual and literary traditions Judaism and Christianity possessed prior to the seventh century CE.[15]

The chief cult of the sixth century (the century before the birth of Ahmad ibn abd al-Mutalib, renamed Muhammad, was devoted to the “generic” god al-llah whose symbol was the crescent moon (derived from Nabataen mythology), a symbolism which lives on in Islamic liturgical practice, calculation, and national flags. Arthur Jeffrey has noted that “The name Al-lah, as the Qur’an itself is witness, was well known in pre-Islamic Arabia. Indeed, both it and its feminine form, al-llat, are found not infrequently among the theophorous names in inscriptions from North Arabia”.[16] The origins of this god are abstract, the name itself deriving from the Semitic root of two letters, the consonant ‘l’ preceded by a smooth breathing, which was pronounced ‘Il’ in ancient Babylonia, ‘El’ (>Eloh, Elohim) in ancient Israel, and in Arabic lah-elided from the definite article to form allah.[17]

Arabic-speaking Jews and Christians used the name for several centuries before the time of Muhammad.[18] The name was later subsumed into Islamic prayer as a monolatrous form of address, but never achieved the magical status assumed by Hebrew יהוה, Yahweh, the national god of the Hebrew tribes after the “conquest”, or infiltration, of the Canaanites.[19]

As a tribal god, Allah himself is agglutinative of characteristics from other members of the Arabian tribal pantheon, modified in connection with traits and attributes derived mainly from what was known and preached by Jewish and Christian-Monophysite and Nestorian teachers in the region. The Qur’an itself is the primary evidence of this agglutinating and borrowing process.[20] Such mixing and borrowing was not uncommon in earlier periods of religious history; in fact, the theophorous YHWH itself probably derives from the Canaanite formula, el dū yahwī ṣaba’ôt, “El who creates the hosts” — a phrase that expresses his special significance as a warrior god who leads armies (hosts) into battle, but later imagined as troops of angels worshipfully surrounding his throne.[21]

In his adapted and roughly finished form, the fundamental characteristic of Allah is to compel belief in himself and punish unbelief; accordingly, the language of the Qur’an is replete with references to God “seeing” what sinners do and being prepared to dole out justice to unbelievers — كفّار (kuffār).

This all-seeing power is not “omniscience”[22] — παντογνωσί — an intellectual attribute in Hellenistic theology often ascribed to divinity — but more on the order of “surveillance” as we find it in ancient paganism.[23] Allah is watchful in the same way the Pentateuchal Yahweh in the early first millennium BCE was understood to be a watchful, wrathful and punishing avenger of human crime and slights to his dignity (Deut. 6.15; 4.24; 5.9).[24] He is watchful because he is cunning and also fearful that mankind is always plotting schemes to evade his plan — which is essentially no more than an acknowledgment of his greatness, expressed in prayer and adoration (Q 2.1; 3:54; 10:21; 13:42).

However, the development of Hebrew theology transforms this primitive deity from a god who commands sacrifice and “righteousness” (Hebrew sedeq, Greek dikaiosyne, literally law-obedience) into one who, beginning with prophets such as Amos, demands a kind of radically ethical change of heart and mind and eschews formalism: “I hate, I despise your religious festivals; your assemblies are a stench to me.” (5.11); and Hosea: “For I desired mercy, and not sacrifice; and the knowledge of God more than burnt offerings” (6.6).

The God of the Hebrew Bible, construed over a millennium or slightly longer, is not figuratively constant. He changes as the social, political and religious context of Hebrew religion changes from a more primitive phase — such as we find in the “Mosaic” law-books reflecting events of the second millennium BCE with their obsession on ritual and purity — to a more benign presence by the 8th or 7th century BCE, the period of the “minor” prophets. The winged deity riding in a chariot, like the noblest Assyrian royal lion-hunter, becomes a god whose only worldly expressions are the classical virtues of love and truth. Islam demonstrates no experience of this evolutionary process.

Philosophical virtues such as wisdom, charity, justice, love and forgiveness flow from that period straight through to the wisdom literature of the fourth century BCE, thence into the common era where they achieve a startling renovation in the ethics of love and forgiveness preached by rabbis like Gamaliel, Hillel, Jochanan ben Zakkai, Yusuf Akiba, and Yeshua ben Iusef, or Jesus. In a sense this ethical revisionism and its consequences for a theory of god were brought about by a political event — the destruction of the second Temple by the Roman forces in 70CE and the passage of religious authority from priests — now jobless — to reformist religious teachers.[25] The God of Israel, as a God of wrath and vengeance who punishes unbelievers, though given honorary position in the sacred books of Jews and Christians, was obsolete by the second century of the common era. The God of power and might (גְּבוּרָה) had been dwarfed by successive losses and political humiliation. New ways to define his dominion and the meaning of the phrase “elect among the nations” had to be found. Islam, which arose in completely different circumstances from the book traditions it presupposed, was unfamiliar with the restrictions that had gone into the making of the God of the Hellenistic era.

The theological revisionism of the Hebrew texts are perforated occasionally by outbreaks of apocalyptic enthusiasm or puritanism (the Essenes, and some rigorist Jewish-Christian sects) that return to the theme of God’s judgement and humanity’s predicament in refusing to “repent” and embrace the “way” — or the gospel, or a messiah, or even a re-conceptualized “Law.”[26] But in general there was a rough theological consensus at the beginning the Christian era that the fundamental attribute of God is love and mercy rather than wrath and a desire for payback. Without collapsing the whole of this development into its most famous restatement, the letter known as 1st John, written in the early second century of the common era, puts the theme this way: “Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God; and everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. The one who does not love does not know God, for God is love” (1 John 4.7-9).

Statistically, the term “love” in one of its Hebrew or Greek variants occurs 491 times in the Revised Standard Version of the Bible and 526 times in the New International Version. The more nuanced 1611 (King James) Bible offers the term 280 times, preferring words like “charity” to “love” during a puritan era that rather hankered after the apodictic policies of the God of Israel.

The term “love of God” or love as an attribute of God occurs nowhere in the Qur’an. By contrast, the phrase “loves not” as a circumlocution for the more direct Hebrew “despises” or spurns is frequent:

Children of Adam! Take your adornment at every place of worship; and eat and drink, but be you not prodigal; He loves not the prodigal. (7.31)

When night outspread over him he saw a star and said, ‘This is my Lord.’ But when it set he said, ‘I love not the setters.’ (6.76)

Call on your Lord, humbly and secretly; He loves not transgressors. (7.55)

So he turned his back on them, and said, ‘O my people, I have delivered to you the Message of my Lord, and advised you sincerely; but you do not love sincere advisers.’ (7.79)

Out of 114 surahs of the Qur’an, 113 begin with the trope, “In the Name of Allah, the All-beneficent (or compassionate), the All-merciful” [bismillah ’ir-rahman ’ir-rahim]. It is sometimes suggested by Islamic experts that this invocation offsets a stream of references to the vengeance and anger of Allah against unbelievers and those who have gone astray (Q1.1-7 passim.). However the phrase is invariably linked to two divine prerogatives: Allah’s right to anger, and his right to condemn. The mercy and compassion of Allah thus consists in the suppression of his anger and his right to pardon (Q42.30). These attributes are typical of the Hebrew tribal God still visible in the pseudo-Mosaic codes of the תֹּורַת מֹשֶׁה, Torat Moshe dating from the late second millennium BCE.[27] They are tantamount to the ancient Near Eastern ideas that a god-king behaves in the same way that an earthly sovereign behaves in relation to his pæons, who are defined exclusively by their obedience to his commands and subject to his judgement.

This very superficial comparison, which I am confident would be borne out by detailed analysis of word frequency and usage, suggests that Islam was largely unaffected by later biblical constructs of the love of God as a defining characteristic of the divine being and thus was substantially unaffected by any written New Testament passages that refer to the teaching of Jesus: Indeed, except for references to his birth, life and status as a “messenger” (e.g., Q19.19) the Qur’an is completely silent about anything that would suggest the Prophet was familiar with the teaching or life of Jesus — or for that matter with any but a few biblical “stories” (such as that of Joseph, the flood, and other tales) that could be pressed into the service of an overarching repetitive narrative about unbelief, penalty and judgement.

Moreover, with just a few exceptions, Quranic references to Jesus are combined with references to his mother, a fair indication that the Prophet’s source of information was an oral Monopshysite and Nestorian missionary tradition (pressing eastward into China in the seventh century) that rejected the idea of Mary as theotokos or Mother of God (God-bearer) and implicitly the equivalence of Jesus and God the Father in Trinitarian orthodoxy. It must be frankly acknowledged that ideological and theological currents from the Bible, especially the gospels, are totally absent from the Qur’an. Muhammad knew only the barest outline of the biblical epic, and in literary and theological terms, he seems to have known almost nothing. There is no mention of the names of the apostles or of a canon or plurality of gospels. Despite a vague allusion to Jesus being “attested” by many miracles (Q2.87), the three most prominent in the Quran (the making of sparrows from mud, the table laden with food, and the Christ child speaking in the manger: 5.112; 19.30; 3.49) are taken from well-known Syriac and apocryphal texts of the third and fourth century. The teaching of Jesus about God, the core of the teaching attributed to him, is totally absent and possibly unknown.[28]

References to “Jesus” within the Qur’an are little more than an attempt to situate him within a genealogy of Prophecy that finds its culmination in Muhammad. There is no plausible “voice” of Jesus in the Qur’an, merely an anti-Christology largely based on the preaching of nomadic Christian missionaries, apocryphal texts, and heretical traditions in which Mary’am figures as a prominent character.

Allah and Archaism

The archaism of the Allah-concept is due chiefly to two factors:

- The isolation of Islamic theology from the philosophical tendencies that affected Judaism from the eighth century BCE onward, and especially after the fourth century, insulated it from the trends of Hellenistic philosophy.

- Conservative-nativist tendencies in Islamic theology, following the death of the Prophet, which made defense of Islam coextensive with defense of the Qur’an and its rudimentary determination of God.

The use of poetic language, metaphor, and poetic figures to describe God is fundamental to even the earliest phases of the biblical epic. By contrast, Islam positively forbade the use of comparison: Associating God with anything or anything with God violated the principle of tawhid:

There is nothing

Whatever like unto Him,

And He is the One

That hears and sees. (Q 42:11)

The corollaries of this belief were twofold: “Allah must be referred to according to the manner in which He and His prophet have described Him without explaining His names and attributes by giving them meanings other than their obvious meanings.” And a reference to God “should strictly abstain from giving Him the attributes of those whom He has created. For instance in the Bible, God is portrayed as repenting for His bad thoughts in the same way as humans do when they realize their errors. This is completely against the principle of Tawhid. God does not commit any mistakes or errors and therefore never needs to repent.”

A morbid fear of what the west would later style “anthropomorphism” governed what was essentially a rejection of poetic diction and imagery in the Qur’an, in the interest of monolatry or tawhid.[29] Yet it was precisely the presence of poetic diction in the Bible — the idea that God could be angered, feel pity, repent of mistakes — that gave the biblical concept its capacity for renovation.

In the west, “God” was a fluid concept — even the fourth century development of trinitarianism proves that fluidity and a lively tradition of speculative thought. In the Islamic world, God was enshrined in a text and caged by a doctrine that prevented any significant further conceptual development. Accordingly, nothing similar to the rabbinical schools or the Christian catechetical schools in Alexandria, Ephesus, Antioch and later Rome arose to challenge this determination. Even in the so-called (and recently much-debated) Golden Age of Islam, from the 9th to the 12th century, advances were not advances in hermeneutics and in theology but in mathematics and sciences.[30] The core doctrines of the faith were unperturbed.

The Qur’an was a closed book (as Omar Khayyam famously complained) and its god-concept a closed topic, guarded by an essentially militant band of imams, muftis and mujtahids (the علماء ʿUlamāʾ), forever limited to the circumstances of its formation. Defended ardently by sultans and others who deferred to the ʿUlamāʾ as the price for patronizing various learned “translation” projects, Allah was intellectually untouchable and thus conceptually confined to the seventh century atavism that found his prototype in the tribes of Abraham.

A radically historical appraisal of the Islamic god-concept, from its tribal origins in the pre-Islamic diaspora of Arabia, to his formulation in the recitations of the Prophet over a relatively short period of time, gives us a snapshot of those attributes that mattered in the emerging mercantile culture of the middle east in late antiquity: toughness, loyalty, obedience to authority, and penalty for those who do not agree or acquiesce in belief. The metropolitan gods of antiquity and late antiquity, predictably, exhibit different traits, and it was in the cities of the Roman world that the god of Judaism and Christianity came finally to rest and to rule.[31] The deity to whom Islam gave birth had been, in conceptual terms, a corpse in Judaism and Christianity for nearly a thousand years.

Because Islamic theology is centered on the idea of “finalism” — Muhammad the final prophet, the Qur’an the final revelation, and its description of Allah the final and only complete description — the pious Muslim must embrace, in some form or other, the belief that all prior formulations are either partial or dangerously wrong, offensive, and sinful. “Islam is exalted and nothing is exalted above it.”[32] The god who loves not transgressors, “setters,” infidels and unbelievers is firmly on the side of the Mujahedeen, those engaged in jihad to protect the uninterpreted and unvarnished faith of the ‘atbae alnnabi, the companions of the Prophet Muhammad. Indeed one of the reasons it is difficult for a devout and conservative Muslim to separate himself entirely from the actions of so-called extremists is that almost no article of faith is more central to classical Islamic teaching than the duty of every Muslim to fight in defense of its unalterable vision of God.

It is difficult, in this connection, to brand the most active pursuers of the defense of Islam “Unislamic” in any way that incriminates them for their zealotry.

This book-bound, fixed, and final determination of God is also inoculated against historical criticism: it explains why Islamic radicalism, not always the violent sort, is largely indifferent or even hostile to history. In their struggle for legitimacy Christian missionaries wrangled with Jewish teachers over questions of interpretation and prophecy, but not over the bare essentials of the Heilsgeschichte — the story of “salvation” prior to Jesus. When a number of heretical groups, especially the second century Marcionites, wanted to scrap the Hebrew Bible and travel with only one gospel and a few of Pauls’ letters, church leaders rounded on them, condemned them, and canonized the entirety of what became the Old Testament — not as an appendix but as a preface to the New. Christianity made no sense and indeed had no real legitimacy apart from “the books of the Jews.” Its core idea of “fulfillment” depended on the essential (if not the literal) accuracy of what came before it. “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them.” (Matthew 5.17).

Muhammad and his followers set the stage to liberate Arab civilization of all forms of idolatry: this meant, practically considered, any book, monument, sect, or custom that was not expressed in the Quran or the laws and traditions that were assumed to flow from it.[33] The contemporary destruction of ancient heritage sites is simply a religious expression — a verdict — on non-Islamic civilization: Palmyra, Mar Elian, Dura Europos, Hatra, Mari, and Nineveh — all looted and damaged — are simply the unfinished business that any true Muslim will regard as commensurate with the actions of the followers of Muhammad and the will of the changeless god of the Qur’an.[34]

Continue reading… part 3.

R. Joseph Hoffmann graduated from Harvard Divinity School and the University of Oxford (Ancient Near Eastern Studies). Hoffmann was tutor in Greek at Keble College and Senior Scholar at St Cross College, Oxford, and Wissenschaftlicher Assistent in Patristics and Classical Studies at the University of Heidelberg. He taught at universities in the United States, Britain and Lebanon. He has held visiting positions at universities in Africa, the Middle East, the Pacific and South Asia. He is now Professor of Liberal Arts at the American University of Central Asia. Beyond academe, he is well known for his advocacy of the humanist tradition. In his recent work, Hoffmann has turned increasingly to the work of ”humanist restoration”. His most recent books include an edited volume entitled Just War and Jihad: Violence in Judaism, Christianity and Islam (2006) and Sources of the Jesus Tradition (2010.) His study of the concept of the right to life in early Christianity, Faith and Foeticide, will be published in 2015, along with another in his series of translations of the classical philosophical critiques of the Christian movement: Christianity: The Minor Critics. He blogs at The New Oxonian. Read his full biography here. For all the exclusive blog entries by R. Joseph Hoffmann, go here.

![]()

Notes:

[14] Crone, Patricia, Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam (Princeton, U.S.A: Princeton University Press, 1987), 134.

[15] Fletcher, Richard, The Conversion of Europe. From Paganism to Christianity 371-1386 AD. London, 1999.

[16] Islam: Mohammed and His Religion, 1958, 85.

[17] Jeffrey, Arthur, Islam, Hammondsworth: Penguin 1954, 1990, p 7, cf. The Legacy of Islam , Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1931; Julius Wellhausen, Medina vor dem Islam (1889), 12.

[18] John Bowman. “The Debt of Islam to Monophysite Syrian Christianity,” in Essays in Honour of Griffithes Wheeler Thatcher (1863-1950), ed. E.C.B. MacLaurin, Sydney, Sydney University Press, 1967, p. 191-216

[19] Smith, Mark S. The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2002. Albright, William Foxwell, Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan: An Historical Analysis of Two Contrasting Faiths, Eisenbrauns, 1990.

[20] Donner, F. M. (2006). Formation of the qur’anic text — the historical context. In J. D. McAuliffe,

The Cambridge Companion to the Qur’an (pp. 23-40). New York: Cambridge University Press.

[21] Allen, Spencer L., 2015. The Splintered Divine: A Study of Istar, Baal, and Yahweh Divine Names and Divine Multiplicity in the Ancient Near East. Walter de Gruyter.

[22] Geach, P., 1977, Providence and Evil, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Rowe, W., 1964, “Augustine on Foreknowledge and Free Will,” Review of Metaphysics, 18: 356–363; Wainwright, W., 2010, “Omnipotence, Omniscience, and Omnipresence,” in The Cambridge Companion to Philosophical Theology, C. Taliaferro and C. Meister (eds.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 46–65; Wierenga, E., 1989, The Nature of God, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

[23] “To the Son of Cronos, Most High, I will sing of Zeus, chiefest among the gods and greatest, all-seeing, the lord of all, the fulfiller who whispers words of wisdom to Themis as she sits leaning towards him. Be gracious, all-seeing Son of Cronos, most excellent and great!” Anonymous. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

[24] Hoffmann, J. and Rosenkrantz, G., 2002, The Divine Attributes, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

[25] Paula Fredriksen, 1988 From Jesus to Christ, Yale University Press. 167-170.

[26] L Michael White, From Jesus to Christianity, San Francisco: HarperCollins, 2004; Hindy Najman, “The Law of Nature and the Authority of the Mosaic Law,” Studia Philonica, 11 (1999), 55-73.

[27] Wellhausen, Julius, Prolegomena to the History of Israel, Scholars Press, 1994 (reprint of 1885 ed.); Davies, G.I (1998). “Introduction to the Pentateuch”. In John Barton. Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press.

[28] The studies in this area are disappointing but see Khalidi, T. (2001). The Muslim Jesus: Sayings and Stories in Islamic Literature. Harvard University Press; Rippin, A. “Yahya b. Zakariya”. In P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers; and Anawati, G. C. “`Īsā Alleh Islam”. In P. J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs. Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers.

[29] Köchler, Hans (1982). The Concept of Monotheism in Islam and Christianity. Braumüller; Rahman, Fazlur (1980), Major themes of the Qur’an, Bibliotheca Islamica.

[30] Bowman, John, “The Debt of Islam to Monophysite Syrian Christianity », in Essays in Honour of Griffithes Wheeler Thatcher (1863-1950), ed. E.C.B. MacLaurin, Sydney, Sydney University Press, 1967. 191-216.

[31] Allen, Spencer L. (2015). The Splintered Divine: A Study of Istar, Baal, and Yahweh Divine Names and Divine Multiplicity in the Ancient Near East. Walter de Gruyter. Cohen, Shaye J.D. (1999). “The Temple and the Synagogue”. In Finkelstein, Louis; Davies, W. D.; Horbury, William. The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 3, The Early Roman Period. Cambridge University Press;

[32] Bat Ye’or (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude. Where Civilizations Collide. Madison/Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press/Associated University Presses; Friedmann, Yohanan (2003). Tolerance and Coercion in Islam: Interfaith Relations in the Muslim Tradition. Cambridge University Press;

[33] Crone, Patricia and Martin Hinds, God’s Caliph: Religious Authority in the First Centuries of Islam (2003; orig. 1986).

[34] Sivan, Emmanuel (1985). Radical Islam : Medieval Theology and Modern Politics. Yale University Press.

RSS

RSS

Latest Comments

Hello Mike, Thank you for your positive feedback to the article. I felt there wasn’t too much critical analysis of ...

Thanks for this considered and well constructed article. A follow up article on the manner in which the editorial contro...

THE CLUELESSNESS OF CLAIMING THAT OBAMA'S MIDDLE EAST POLICIES WERE A FAILURE CANNOT BE FURTHER FROM THE TRUTH, WHAT THE...

As long as Obama is the president of the usa do not trust the us government......

Thank you for an good read....