![]()

Tuesday, January 12, 2016 | by R. Joseph Hoffmann | American University of Central Asia

Transactional Implications of the God-Concept in Islam

This article is the nucleus of a manuscript by R. Joseph Hoffmann which will be published by Prometheus Books later this year. Due to its length, it’s printed here in three parts. You can read part 1 here and part 2 here. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of CrethiPlethi.com.

Allah and Guilt

Prophet Muhammad’s heart cleansed of impurities by the angel Gabriel in preparation for his ascent to heaven watched by other angels. From the 16th-century manuscript The Progress of the Prophet (Turkey). Note: To circumvent prohibitions against depicting the Prophet Muhammad, portrayals of the Prophet often showed him with his face blank or hidden. Thus, not actually drawing Muhammad, but only his clothes. Several historians and scholars believe that some of the faceless Muhammad portrayals may have been originally drawn with faces, but were later scratched out.

The atavism of the eighth century god-concept in Islam has implications for a significant number of auxiliary doctrines. Of these, the one with the most direct bearing on the psychology of belief in Islam at a transactional level is the understanding of guilt and contrition.

Between the Hebrew God who punishes sons for the sins of their fathers “even unto the fourth generation” (Exodus 20.6; Deut. 5.9) and the God of Jesus who commands forgiveness of transgressions “seventy times seven” (Matthew 18.22) there stands a period of about 1200 years, endless wars, migrations and dispersions, and significant intellectual infiltration from nations as far removed as Babylon, Greece, Persia and Rome. The impact on the god-doctrine and on the understanding of the divine-human relationship, in both religious and practical terms, was inevitably profound: the Jews had to make sense of persistent humiliation and defeat against the belief that their God was unique and superior to the gods of the nations. Whereas the expansionist mandate of Islam was a part of its earliest agenda, Judaism’s reaction to its neighboring states was to “draw a hedge [khumrot] around the law” and accept that the promise to Abraham (Gen. 17.4-16) was no longer a live option in political terms.

This led to a long habit of introversion and intellectual restructuring that included considerations of the nature of sin, punishment, forgiveness, and “reconciliation” which is translated from the Hebrew word Kippur (Greek, katallage) to the self-defining word (and the only theological term expressly English) atonement (at-one-ment).

The thinking of the first and second centuries of the common era had arrived at the point where individual blame and individual guilt were simply commentaries on a condition inherent in human nature — a rebelliousness (ἀποστασία) that alienated mankind from the love and forgiveness of God through the habitude of sin. In evolving rabbinical thought, God was a loving father, not an avenging dispenser of justice — or, as in the story of the prodigal son — willing to forgive repeated instances of abuse and willfulness in exchange for the slightest indication of remorse — דַּכָּא, dakka, or humility. For the rabbis and expressly also for Jesus and Paul, the temple cult obscured this theology with its emphasis on formalism, forensic retribution, and sacrifice.[35] If there is even a grain of truth to the story of Jesus “cleansing the temple” of viperous money changers (Mark 11.15-19)[36] it is that Judaism had outgrown the temple long before the Romans set fire to it. The cyclical nature of the way the priests controlled the temple cult for profit was — to use another term current in first century Jerusalem reformist circles, — an abomination (תּוֺעֵבָה), something detested by God as impure and usually associated with idols in the older religious texts. Moreover, Temple ritual and the regimen of the lawyers ensured that God’s mercy could be formally accessed only once a year — on the yom kippur or “day of atonement,” “the tenth day of [the] seventh month” (Tishrei) when God sealed the fate of sinners who prayed and offered sacrifice for sins committed in the preceding months.

In the period of the Temple, the priesthood was the standard way of dealing with the universal condition of sin (חָטָא). The Temple was not a place of worship but a center of corporate expiation, focusing on the sacrificial cult run by the priests and the Sadducee elite. The existential crisis in the Temple came from an awareness of temple politics, especially the reputed money grubbing and corruption of the priestly power-brokers under the Hellenized Hasmoneans. The collective outrage and stress was enough to drive a devout monastic minority out to the caves around Khirbet Qumran on the shores of the Dead Sea to pray for a deliverer — a new “teacher of righteousness.”[37]

Both the rabbis and early Christian teachers understood the bond between God and humanity to be essentially broken; Christian theology originated in the conviction that alienation is the normal state of affairs between God and man. Paul’s pessimistic (but entirely rabbinical) view that all have sinned (Rom. 3.23, Isa. 53.6) and that “righteousness” (a status increasingly identified as moral and existential, rather than as obeying the old pharisaic law codes, now practically moot) was entirely in keeping with the creeping theological modernism that flowed out of Hellenistic Judaism in the second century BCE.[38]

The new understanding of human nature entailed a distinction, indeed a conceptual rupture, between holiness (or purity) and moral discernment, activated by “faith” (πίστις) or trust in the love of God and the χάρις (grace or favour) shown to the generality of humanity. For the early Christians, or such of them as were paying attention, reconciliation was not something to be achieved through individual human effort; it was granted freely by God on the basis of a likeness between God and man personified in Jesus Christ (Romans 3.10, 24). The Jesus of orthodox Christianity was the mordant contradiction of the later Islamic belief that nothing exists alongside (equal to) God, nothing that justifies man in thinking he is forgiven for going astray: words like justification, grace, and faith acquire a whole new balance within this theological matrix. Islam’s vague acknowledgement of this is to commandeer the biblical and theological Jesus into the ranks of the prophets, a true Muslim, the son of Mary, but without any other special significance: “In blasphemy indeed are those that say that Allah is Christ the son of Mary. Say: ‘Who then hath the least power against Allah, if His will were to destroy Christ the son of Mary, his mother, and everyone that is on the earth?’ For to Allah belongs the dominion of the heavens and the earth, and all that is between. He creates what He wishes. For Allah alone has power over all things.” (Q 5:17 cf., 72, 116)

Islam at its inception, as a form of post-Judaic monolatry, and with no native philosophical tradition to build on, regressed to the importance of holiness, purity and “technical” obedience to commands as the tokens of true faith, and avoidance of God’s wrath as the incentive for staying pure. “Declare (O Muhammad) unto My slaves, that truly, I am the Oft-Forgiving, the Most-Merciful. And that My Torment is indeed the most painful torment” (Q15:49-50). There are no signs of an imprint of rabbinical Judaism or patristic Christianity, no jesuine message of conscience, the ἀγάπη (agape) or higher form of love that expresses itself in communal and social bonds, “the kind of love that is passionately committed to the well-being of the other.” From the start there was a fundamental and organic difference between the Islamic idea of ummah or a brotherhood of believers and the Christian idea of ecclesia or “church” — already a physical entity within the New Testament (1 Cor. 1:2; 2 Cor. 1:1; Eph. 1:22-23, Acts 2:47). But these communities seem to have been stubbornly local and to have believed different things about Jesus. It is only much later that theological consolidation becomes possible, and when it does, in the fourth century, it does so largely by sacrificing the biblical Jesus for a renovated doctrine of God.

The ummah (أمة) was based on a shared recognition of the power of Allah to judge, reward (Jannah, Paradise) and condemn (Jahannam or al-Nar, hell or fire). While Christianity did not wipe away these motifs, it substituted for the raw eschatology of earlier ideas the belief that what one does after baptism must be done on the basis of love and conscience and in response to the divine love thought to be uniquely expressed in the charis provided by God in the death of Jesus (Matthew 5:43-46; John 3.16).

Indeed the silence of Islam to show any awareness of a rupture between Judaism and Christianity is a significant proof that Muhammad and his followers were confused about important disparities between the two earlier religions, especially in the matter of prophecy and its interpretation, and the vital classification of books that sequestered the prophetic elements of the Bible, the Nevi’im, from the Torah (law) and the Ketuvim or writings. By collapsing these divisions (which form a kind of hierarchy in Judaism, while the torah occupied an ambiguous place in prophecy-obsessed early Christianity) Muhammad could enlist any important name as a prophet: Adam, Abraham, Lot, Isaac, Moses, David, Aaron. Noah and Solomon are all prophets, while with just a few exceptions the Hebrew prophets most important to Christianity are not mentioned at all — until later writers like ibn Kathir invent stories about them based on familiar Jewish legends.

A prophet in the Quranic sense is simply someone who had preached Islam, including Isa (Jesus) and Yahya (John the Baptist); all prophets had the same message and preached the same thing (Q42.14). While Christian teachers had insisted that the Hebrew prophets were “foretellers” of the gospel, the Islamic approach was to establish a dynastic succession of worthies, beginning with Adam, who had proclaimed the same truth since the beginning of creation — a Who’s-who of forerunners ripped from historical context in order to secure Muhammad’s legitimacy.

While the Christian “heresies” abroad during the period of Muhammad showed a full recognition of the intellectual dynamics and scriptural texts upon which the dialogues and debates were built,[39] Islam stands totally outside this discussion, largely because it was not engaged with hermeneutics but with the question of authority. The actual substance of what a prophet might have said, or when — his intellectual matrix — was essentially irrelevant to Muhammad’s project. That project was to build an obedient community of believers subject to the authority of a book that had been largely manufactured in the period of the caliphate from bits and pieces of kerygma (oral preaching) and scraps of written tradition, neither thematically nor chronologically ranked and lacking both coherence and literary quality. Islam possessed from the beginning a keen if rather contorted sense of authority, judgement, reward and punishment:

Quran 9:5

“Then, when the sacred months have passed, slay the idolaters wherever you find them, and take them (captive), and besiege them, and prepare for them each ambush. But if they repent and establish worship and pay the poor-due, then leave their way free. Lo! Allah is Forgiving, Merciful.”

Quran 22:19-22

“Fight and slay the Pagans, seize them, beleaguer them, and lie in wait for them in every stratagem….as for them (the unbelievers) garments of fire shall be cut and there shall be poured over their heads boiling water whereby whatever is in their bowels and skin shall be dissolved and they will be punished with hooked iron rods.”

Quran-8:67

“It is not for any prophet to have captives until he has made slaughter in the land. Ye desire the lure of this world and Allah desires (for you) the Hereafter, and Allah is Mighty, Wise.”

There are approximately 2900 verses of similar valence (1000 about threat or wa’id), but the total effect is to underscore the point that the nature of Allah is the nature of a monocrat with his minions obliged to do his bidding, suffer his punishments, accept his laws, and kill those who do not bow to persuasion. Neither the religions of the ancient Near East, including the Assyrian or the Hebrew, nor later the Babylonians or the Persians, provide an exact analogue for the religion of the early Muslims, particularly since the Arabs in the seventh century rejected the idea of kingship which was characteristic of all other ancient Near East and Hellenistic societies.

By the beginning of the Common Era, the defining feature in both Jewish and Christian theology at a transactional level is the doctrine of contrition. In a literary form, the belief is prominent in Psalm 51:1-10:

Have mercy upon me, O God, according to thy loving-kindness; according unto the multitude of thy tender mercies blot out my transgressions. Wash me thoroughly from mine iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin. For I acknowledge my transgressions; and my sin is ever before me. Against Thee, Thee only, have I sinned… Behold, Thou desirest truth in the inward parts; and in the hidden part Thou shalt make me to know wisdom. Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean; wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow… Hide thy face from my sins, and blot out all mine iniquities. Create in me a clean heart, O God; and renew a right spirit within me…”[40]

The diction of the Psalm provides a remarkable contrast to the Quranic idea of Allah as more cunning and more deceitful than his creatures, entitled to his supreme position because he is the best of liars — a makir

“And they cheated and God cheated, and God is the best of the deceivers (Q3.54)

“And when those who disbelieved deceive/scheme at you to affix/affirm you, or kill you, or bring you out, and they scheme/deceive, and God deceives and God (is) best (of) the deceivers” (8.30)

“Did they secure God’s deceit? So no one trusts God’s deceit except the nation of the losers [unbelievers]” (7.99; cf 10.21; 13.42)

This vestige of Arabic fatalism means that there can be no “god-likeness” in man since the relationship is based on mutual distrust: man is deceitful, cunning, a double-dealer and a schemer, but Allah’s schemes are larger, his craftiness and his power to plot and to deceive absolute. There is no ontology of human nature and sin, no discussion of the way in which a “sinful creature” through reparation and sorrow can achieve “godliness” — indeed, such an idea is not only foreign but blasphemous in Islam.

The Mysterious Lack of Likeness

Islam developed no doctrine of contrition and corporate human responsibility for wrongdoing (a belief that would culminate in the early medieval doctrine of “original sin”) because its doctrine of god did not accommodate such a belief: Islam did not have to contend with the scriptural assertion (Gen 1:26–28; Gen 5:1–3) that man was created in the image of God — צֶלֶם אֱלֹהִים. (tzelem Elohim). The Quran has no corresponding passage and hence no corresponding doctrine, and it is likely that the monolatry of the Quranic period would have rendered such an idea irtidād or apostasy. Instead, the Quran offers a number of inconsistent declarations that seem to suggest either ignorance of the Hebrew creation story, or an attempt to refashion what was known of it:

In the name of your Lord…who created man, out of a mere clot of congealed blood.

(Q 96:1-2)

It is he who has created man from water.

Q25:54)

And God has created every living creature from water.

Q 24:45)

We created man from sounding clay, from mud molded into shape.

(Q 15:26)

Amongst his signs is this, that he created you from dust.

(Q 30:20)

The scattered references to creation thus support Islam’s central idea: there is an absolute ontic distance of power and purpose that is not bridged by any principle that would harmonize or compare the two modes of existence, creature and Creator. As we have already seen, the term “atonement” in the western theological sense is not present in the Quran: man and God, human and divine, are stubbornly opposite in nature. The Arabic term najat has no clear resemblance to the Christian idea of salvation and means simply being spared the pains of hell or entry into paradise by virtue of being a Muslim (Quran 19:67–72; 57.22).

Since the Judaic and Christian idea that the image of God in man was occluded by sin and needed to be restored, the earlier book traditions differed markedly from Islam in the way in which salvation, as a process, comes about. Judaism and Christianity agreed that the loss of the imago dei created a certain spiritual disability in humankind that impaired will and judgment; the loss could not be compensated for simply by acknowledgement or desire.[41]

Islam is completely indifferent to this existential plight and its consequences: There is no “fall” in Islam: Islam acknowledges the sin of Adam, says Anawati,[42] but this sin “has had only personal consequences. Moreover, their fault has been forgiven” (Q2.38). The idea of an original sin transmitted by Adam to his descendants as a contagion is absolutely opposed to the teaching of Islam. Hence, the Jewish and then the more developed Christian emphasis on contrition and a personal “will to do good” as an activating feature in the process of reconciliation.

Second Temple Judaism located the source of sinfulness in human nature: six different terms are used to describe the valences of sin, ranging from chata (חָטָא) which is used about 260 times and means to go or do wrong (missing the mark) to rasha, which means a state of wickedness or evil, contrary to God’s nature. The common Greek word in the New Testament is hamartia, which approximates to going astray or “missing the mark.” Sin is endemic, social, incapacitating. It requires a change of heart — repentance, contrition — and amendment. From the second century to the time of Augustine in the fifth century, Christian theology, working out of its Jewish past, would develop the belief that it a natural response to the love of God and not fear of his wrath that leads to moral change demanded for salvation.

By the sixteenth century, building on a long history of discussion, the Roman Catholic Church defined its doctrine canonically; but similar, if more scripturally-based definitions were coming out of Germany and Geneva, from the writings of Reformers, obsessed with the question of how the human person can be “simul justus et peccator” (Luther) — both good and sinful at the same time. Trent called the condition for this status “interior repentance” (Sess. XIV, ch. iv de Contritione): “a sorrow of soul and a hatred of sin committed, with a firm purpose of not sinning in the future,” or “sorrow of the soul and detestation for the sin committed, together with the resolution not to sin again” and compunctio cordis (repentance of heart). The Council went on to distinguish the “perfect contrition” which causes a change of heart for “love of God” and imperfect contrition (or attrition), in which one repents for reasons other than the love of God, such as the fear of Hell. The moment in the history of the western religious tradition marks the official abolition of fear of God and hell as a sufficient motive for repentance. The restoration of the “image of God” which is triggered by love and activated by contrition and repentance required a fundamental rethinking of the nature of God. Desiring God, or — more specifically — to be more “godlike” in purpose, will, and act, had been set off from what had always been a relatively minor theme in Judaism and never — except at a popular level — a major theme of Christian theology: desiring heaven.

Conclusions

For its part, Islam was never able to rise above or move beyond the popular level. Its doctrine of Allah was ironclad if atavistic. Its religious teachers were unanimous and repetitive. Allah exists to be worshiped. Prophets, who are proto-Muslims, were sent to warn and to condemn. Their message is consistent and unvarying. A believer is one who believes in Allah and his Messenger, and fears the righteous punishments of Allah. Because of its insistence that creator and creature stand in a diametric relationship, compatible indeed with that between men and gods in primitive mythology, its doctrine of salvation was infantilized and could not develop intellectually beyond the most rudimentary “facts” recorded in its sacred book.

The sacred book, the Qur’an itself, possesses a history that we are still piecing together, a task made more difficult by the fact that basic textual and redaction critical methods developed in the West are considered taboo by the vast majority of Islamic scholars as having been developed by unbelievers.[43] This in itself is a scandal in modern scholarship, since (especially in academic areas where Islam is an object of study) a high degree of parochialism has come to be accepted. In no other area of investigation would dogmatic prejudices be permitted to determine the course of serious academic discussion and discovery.

It does seem that entire sections of the Qur’an pre-date the time of Muhammad and some seem to have a Christian provenance. Longer slivers of tradition — Surah 12, for example — seem to be lifted directly from a paraphrase or targum of Genesis 39, though very few such extensive parallels exist, and it is not clear why.

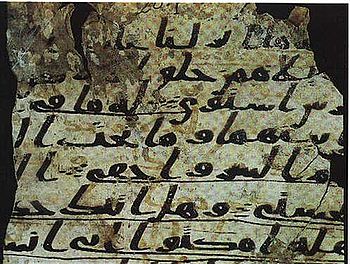

Gerd R Puin photo of one of his Sana’a Qur’an parchments.[44]

What the West has to acknowledge is that even the most liberal mosque in Santa Barbara has yet to embark on this intellectual journey. There are well-endowed centers for Islamic studies in Oxford, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Munich and throughout Europe. They thrive on money pumped in from, largely, Sunni benefactors. Yet none would be prepared to embrace a completely non-apologetic and non-parochial stance towards Islam and its foundational texts.

This being so, it is no wonder that the people Ibn Rushd regarded as “beginners” — those who needed religious instruction and could not follow argument, understand poetry, supply context, or appreciate the hidden religious truth beneath the surface of a text, will dominate the psyche of the Islamic world for a very long time to come. Except for the efforts a few brave western scholars — Gerd Puin, Christoph Luxembourg, Marcus Groß — to climb the tower, Allah is secure on his scriptural throne, protected not just by his avenging angels but by a complacency toward the historical critical method that is unrivaled in scholarship.

R. Joseph Hoffmann graduated from Harvard Divinity School and the University of Oxford (Ancient Near Eastern Studies). Hoffmann was tutor in Greek at Keble College and Senior Scholar at St Cross College, Oxford, and Wissenschaftlicher Assistent in Patristics and Classical Studies at the University of Heidelberg. He taught at universities in the United States, Britain and Lebanon. He has held visiting positions at universities in Africa, the Middle East, the Pacific and South Asia. He is now Professor of Liberal Arts at the American University of Central Asia. Beyond academe, he is well known for his advocacy of the humanist tradition. In his recent work, Hoffmann has turned increasingly to the work of ”humanist restoration”. His most recent books include an edited volume entitled Just War and Jihad: Violence in Judaism, Christianity and Islam (2006) and Sources of the Jesus Tradition (2010.) His study of the concept of the right to life in early Christianity, Faith and Foeticide, will be published in 2015, along with another in his series of translations of the classical philosophical critiques of the Christian movement: Christianity: The Minor Critics. He blogs at The New Oxonian. Read his full biography here. For all the exclusive blog entries by R. Joseph Hoffmann, go here.

![]()

Notes:

[35] “Rabbi, Rabbinate,” article in the Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd ed., vol. 17, pp. 11–19, Keter Publishing, 2007.

[36] Sanders, E P, Jesus and Judaism, Philadelphia, 1975.

[37] Alvar Ellegård; Jesus — One Hundred Years Before Christ: A Study In Creative Mythology, London (1999).

[38] Wright, N T, Romans and the Theology of Paul, Philadelphia, 1995, 30-67.

[39] Philippe Bobichon (ed.), Justin Martyr, Dialogue avec Tryphon, édition critique, introduction, texte grec, traduction, commentaires, appendices, indices, (Coll. Paradosis nos. 47, vol. I-II.) Editions Universitaires de Fribourg Suisse. The most famous epitome of an debate between a Christian and a Jewish teacher of the second century.

[40] Miles, Jack, God: A Biography, Vintage, 1996.

[41] Ricoeur, Paul (1961). Translated by George Gringas. “The image of God and the epic of man”. Cross Currents 11 (1); Ratzinger, Joseph [Pope Benedict XVI], “In the Beginning: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall, (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995), 44-45, 47.

[42] George Anawati, “La notion de ‘péché originel’ éxiste-t-elle dans l’Islam?” from Studia Islamica, Vol.31, G-P. Maisoneuve-Larose, Paris, 1970, p. 32.

[43] Luxenberg, Christoph (2000) — Die Syro-Aramäische Lesart des Koran: Ein Beitrag zur Entschlüsselung der Koransprache. Berlin: Verlag Hans Schiler; and see Lester, Toby (January 1999). “What Is the Koran?”. Atlantic Monthly. ISSN 1072-7825.

[44] Retrieved 5 November 2014; Puin, Gerd-R. (1996). “Observations on Early Qur’an Manuscripts in Ṣanʿāʾ”. In Stefan Wild. The Qur’an as Text. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. pp. 107–111.

[45] Averroes (April 14, 1126 — December 10, 1198) is the Latinized form of Ibn Rushd, full name ʾAbū l-Walīd Muḥammad Ibn ʾAḥmad Ibn Rušd.

RSS

RSS

Latest Comments

Hello Mike, Thank you for your positive feedback to the article. I felt there wasn’t too much critical analysis of ...

Thanks for this considered and well constructed article. A follow up article on the manner in which the editorial contro...

THE CLUELESSNESS OF CLAIMING THAT OBAMA'S MIDDLE EAST POLICIES WERE A FAILURE CANNOT BE FURTHER FROM THE TRUTH, WHAT THE...

As long as Obama is the president of the usa do not trust the us government......

Thank you for an good read....