![]()

Winter, 2017 | The Middle East Quarterly, Volume 24, Number 1 | by Richard Landes

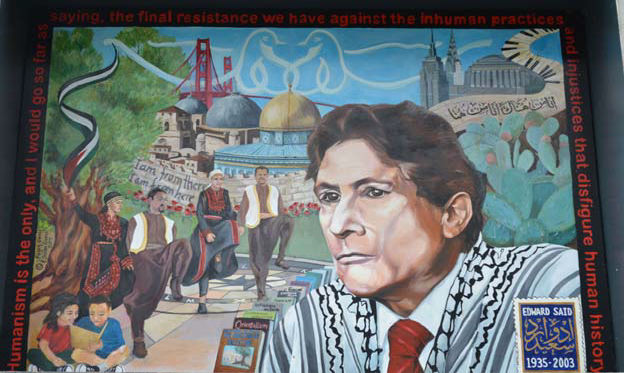

Edward Said, here in a Palestinian mural, assembled a wide range of “post-colonial” acolytes in many fields in the social sciences and humanities. However, following Said, scholars and journalists have underplayed the role of honor-shame cultures in Arab and Muslim societies and its impact on Islamic religiosity, all of which he tarred with the derogatory brush of “Orientalism.”

Whether one views the impact of Edward Said (1935-2003) on academia as a brilliant triumph or a catastrophic tragedy, few can question the astonishing scope and penetration of his magnum opus, Orientalism.[1] In one generation, a radical transformation overcame Middle Eastern studies: A new breed of “post-colonial” academics, boasting a liberating, anti-imperialist perspective, replaced a generation of scholars disparaged by Said as “Orientalists.” Nor was this transformation limited to Middle Eastern studies: Said and his post-colonial paradigm assembled a wide range of acolytes in many fields in the social sciences and humanities.

And yet, when one surveys the past two decades alone, Said’s academic progeny have been spectacularly off the mark in their analyses of and prescriptions for action in the Middle East; and nowhere has this been more apparent than in the misreading of the disastrous Israeli-Palestinian Oslo “peace process”[2] and the “Arab spring,” with its rapid deterioration into a welter of tribal and sectarian wars that have, among other things, created millions of refugees, many of whom have literally washed up on Europe’s unhappy shores.

Much of this failure can be attributed to the strictures placed by post-colonial thought on the ability to discuss the Middle East’s social and political dynamics:[3] If scholars and journalists were mesmerized by the prospects of Arab-Israeli peace and the mirage of a wave of Arab democratization, it was partly because they had systematically underplayed the role of honor-shame cultures in Arab and Muslim societies, and its impact on Islamic religiosity, all of which Said had tarred with the derogatory brush of “Orientalism.”

Honor-Shame Dynamics: Political and Religious

The term honor-shame designates cultures where the acquisition, maintenance, and restoration of public honor trump all other concerns. While everyone cares what others think and wants to save face even if it means lying, in honor-shame cultures, such concerns dominate public discourse: There is no price too high to pay — including one’s life — to preserve honor. In such political cultures, public opinion accepts, expects, even requires that blood be shed for the sake of honor.[4] In such societies, when people voice public criticism of those in power — those with honor — they attack their very being; were the latter not to respond — preferably through violence — they would lose face. Authoritarian societies accordingly enable their alpha males to suppress violently those whose language offends them. Hence, honor-shame cultures have immense difficulty tolerating freedom of speech, of religion, of press, and an equally hard time dealing with societies that do.[5]

In self-help justice cultures, this insistence on honor can mean killing someone who killed a relative, and in Japanese culture, honor can mean killing oneself. However, in some honor cultures, this concern means killing a family member for the sake of the family’s honor. And driving the performances, motivating the need to save face, and defining the ways to do so is “public judgment,” whose verdict decides one’s fate in the community. The Arabic term for gossip is kalam an-nas (talk of the people), which is often harsh in its judgment of others. Psychologist Talib Kafaji writes,

Arab culture is a judgmental culture, and anything a person does is subject to judgment … induc[ing] many fears … with serious consequences on individual lives. Avoiding such judgment can be the constant preoccupation of people, almost as if the entire culture is paralyzed by Kalam [an]-nas. In other words, all of the people in Arab society are hostages of each other.[6]

Despite sounding “Orientalist,” this attention to a crippling and pervasive judgmentalism provides important insights into the dysfunctions of the Arab world today.[7]

Jerusalem. The honor-shame dynamic explains much of the Arab and Muslim hostility to Israel. A state of free Jews (i.e., non-dhimmi infidels), living inside the historic Arab Dar al-Islam, constitutes blasphemy. Israel’s ability to survive repeated Arab efforts to destroy it constitutes a permanent state of Arab shame before the entire global community.

Honor-shame cultures tend to be zero-sum: Men of honor jealously guard their honor and view others’ rise as a threat to self.[8] In zero-sum cultures of “limited good,” honor for one person means shame for others. If the other side wins, you lose; in order to win, the other side must lose. Those just below continuously challenge those just above, and ascent comes through aggression.[9] You’re not a man until you’ve killed another man. Taking from another — theft, plunder — is superior to producing. Rule or be ruled. One washes a blackened face in blood.

The same hard zero-sum, rule-or-be-ruled, mentality that dominates most interactions in the politics of honor-shame cultures, has its analog in the religiosity of triumphalism, or the belief that the dominance of one’s religion over others proves the truth of that religion.[10] In the same way that triumphalist Christians took the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity as proof of their supersessionist claims about the Jews,[11] triumphalist Muslims, in a supreme expression of honor-driven religiosity, believe that Islam is a religion of dominance destined to rule the world.[12]

This honor-shame dynamic explains much of the Arab and Muslim hostility to Israel, as well as to the West. Israel, a state of free Jews (i.e., non-dhimmi infidels), living inside the historic Dar al-Islam (realm of submission), constitutes a living blasphemy; and Israel’s ability to survive repeated Arab efforts to destroy it constitutes a permanent state of Arab shame before the entire global community.[13] This in turn makes triumphalist Muslim hostility to Israel a particularly severe case of a much broader hostility toward infidels and “moderate” Muslims.

Any effort to understand what is happening in the Arab world today needs to take into account this religio-cultural dynamic. And yet, by and large, this dynamic is not only ignored but those underscoring it are rebuked for (supposedly) contributing to worsening the conflict rather than understanding it.[14] Much of this ignorance (both active and intransitive) can be traced back to Said, who made “honor-shame” analysis an especially egregious “Orientalist” sin.[15] Even before his work anthropology had moved away from such analysis, he made it dogma. So much so, that in the last third of the twentieth century, it became paradoxically shameful — indeed racist — for an anthropologist to discuss Arab or Muslim “honor-shame.”[16]

Said’s Shame and the Disorientation of the West

Said’s Orientalism exploited a Western proclivity for moral self-criticism over criticism of other cultures to shield his people from shame. For him, criticism of Arabs or Muslims reflected the West’s ethnocentric prejudices and its discriminatory, cultural map for imperial dominion. It was not what the Orientalists pretended they were doing, namely, offering accurate observations on the characteristics and conditions of another culture and its history.[17] Rather, any contrasts between the cultures of the democratic West and those of Arabs and Muslims — certainly any that put the latter in a poor light — were ugly examples of invidious xenophobia directed at an inferior “them,” not a reflection on a social reality. Speaking of the nineteenth century, Said wrote: “[E]very European in what he could say about the Orient, was consequently a racist, an imperialist, and almost totally ethnocentric.”[18] He issued a plea for an alternative:

At all costs, the goal of Orientalizing the Orient again and again is to be avoided … Without “the Orient” there would be scholars, critics, intellectuals, human beings, for whom the racial, ethnic, and national distinctions were less important than the common enterprise in promoting human community.[19]

Unpacked, this appeal asks scholars not to talk about ethnic, racial, or religious differences — what most Middle Easterners will say are very important cultural issues for them. Hence, in his 1994 “Afterward” to a new edition of Orientalism, Said complained about the growing Western focus on Islam as a danger: “both the electronic and print media have been awash with demeaning stereotypes that lump together Islam and terrorism, or Arabs and violence, or the Orient and tyranny.”[20] Such phenomena, Said insisted, were “not part of the whole picture” and focusing on them “demeans and dehumanizes lesser people … [and] denies, suppresses, distorts.”[21] In essence, Said enjoined fellow non-Muslims to ignore the very issues they most needed to understand in order to follow the developments of the twenty-first century.

Hence, the very factors now dominant in Arab and Muslim political culture — religious zealotry, violence, terrorism, unbridled authoritarianism, and exploitation of the weak, including women, refugees, and, of course, the perennial victims of Arab political culture, the Palestinians,[22] are not to be mentioned because doing so belittles Arabs and Muslims and hurts their feelings. Those who violate these new, anti-Orientalist directives elicit predictable anger from those they criticize, and equally vehement, if less violent, protests from fellow Westerners, accusing the Islamic critics of racism and of blaming the victim. Those who criticize Muslim hate speech are accused of aggravating the conflict.

Israeli troops during the 1967 Six-Day War. Said experienced the catastrophic Arab defeat during the war as a “punishing destiny.” As a “Palestinian,” he lost face in this catastrophe, and his honor response was anger at those who thought badly of Arabs and who claimed to hold the moral high ground.

So even as the traits that Said branded racist stereotypes grew in strength in the “Orient,” the mandarins of Middle East studies and post-colonial academics discussed them only reluctantly, and when pushed to do so, primarily to play them down.[23] As a result, Western audiences remain to this day misinformed about Arabs and Muslims.

While Said framed his critique of the West in post-modern, humanistic terms, it may well be framed in terms of the cultural dynamics of honor-shame. Kalam an-nas — the public opinion whose disapproval is so painful — helps to explain the direction of Said’s thought leading up to Orientalism. As an Arab who had great success playing by Western rules, surrounded by admiring colleagues (his “honor world” to that point),[24] Said experienced the catastrophic Arab defeat of the 1967 Six-Day War as a “punishing destiny”:

The web of racism, cultural stereotypes, political imperialism, dehumanizing ideology holding in the Arab or the Muslim is very strong indeed, and it is this web which every Palestinian has come to feel as his uniquely punishing destiny. No [American academic] culturally and politically ever identified wholeheartedly with the Arabs; certainly there have been identifications on some level, but they have never taken an “acceptable” form as has liberal American identification with Zionism.[25]

As a “Palestinian,” Said had lost face in this catastrophe, and his honor response was not a self-critical look at the Arab attitudes and actors that had contributed to both the unnecessary war and catastrophic defeat, but rather, anger at those who thought badly of Arabs and who claimed to hold the moral high ground. Accordingly, he showed no concern for whether or not the Palestinian cause, whose “wholehearted” support he endorsed and wished others to share, reflected (or disdained) the liberal values to which he appealed. For the honor driven, championing a side in a conflict is not about integrity or liberal values, but about honor, about how one looks, about “face.”

Not surprisingly, few topics so incensed Said as the discussion of the role in Arab culture of seeking, maintaining, and regaining honor, and avoiding and eliminating shame. Given that such cultural traits as misogynistic patriarchy, honor-killings, blood feuds, slavery, civilian massacres, etc., did not look very good to Western liberals, Said had to save Arab face by averting that hostile occidental gaze. In a brilliant move, by labeling it racist, he managed to make it shameful for Western academics even to refer to these matters in discussing the Arab world.

His Orientalist playbook, by contrast, demanded a moral and cultural affirmative action. Accordingly, Said and his acolytes rebuked anyone who dared explain the perduring Arab Muslim obsession with destroying Israel in terms of their cultural issues: “How dare you treat them like they’re a bunch of savage, irredentist, superstitious yahoos, who feed on fantasies of genocidal revenge to restore honor lost and to retake dominion?!” On the contrary, Said insisted, “the connection between Arabs, Muslims, and terrorism” that so many “Orientalists” make was “entirely factitious.”[26] For any outsider to suspect Palestinian (or Arab or Muslim) leaders of culturally-embedded, belligerent behavior, constituted, for post-colonials, an unacceptable aggression, a form of racism.[27] For them, the conflict is about Israeli imperialism and the natural resistance it provokes.

With this brilliant defense of Arab face, of dealing with kalam an-nas, Said’s Orientalism flipped the vectors of the paralyzing negative judgment. On the one hand, it shielded Arabs from public criticism, on the other, it made the “imperialist” West (and its supposed outpost, “colonial Israel”), the object of relentless criticism. His success in this regard, gave rise to a generation of Middle East specialists, including academics, who described the Arab and Muslim worlds as “thriving civil societies,” imminently “democracies,”[28] even as they berated the democratic West as a racist, imperialist culture badly in need of deconstruction, theoretically and practically. Such a move may have flattered Arab and Western (progressive) self-images, but it came at the cost of ignoring the darker realities on the ground.

And yet, to many, that ignorance seemed like a small price to pay. After all, Said’s framework offered conflict-averse progressives a way to avoid a clash of civilizations. Give Arabs and Muslims the benefit of the doubt, treat them with honor rather than gratuitously incensing them with criticism. That is the way to solve conflicts and bring peace.[29] Educated Western adopters of Said’s discourse saw it as a kind of therapeutic narrative, which, by accentuating the positive and glossing over the negative, encouraged, rather than alienated, the “other.”[30] It meant, among other things, treating Arabs and Muslims as if their political culture had already reached modern levels of societal commitment to universal human rights, to peace through toleration, to egalitarianism, to favoring positive-sum relations — when in reality, such an assessment was not only not objective (as in the post-modern world it cannot be), but also very far from any accurate assessment (which presumably it claims to be).[31]

From Oslo “Peace” to Jihad

Few debacles better illustrate the folly of ignoring honor-shame dynamics than the Oslo “peace process,” which based its logic on the principle of an exchange of “land for peace”: Israel cedes land to the Palestinians (most of the West Bank and Gaza) to create an independent state; the Palestinians bury the hatchet of war since they’re getting what they allegedly want, without the need for war.

PLO chairman Yasser Arafat accepts the Nobel Peace Prize, December 10, 1994, Oslo. After the signing of the Oslo peace deal and the granting of the Nobel prize, Arafat found himself the target of immense hostility from his Arab and Muslim honor-group for having brought shame upon himself, his people, upon all Arabs and all Muslims.

Thus the accords banked on a Palestinian shift from their charter-defined commitment to regaining Arab and Muslim honor by wiping out the shame that is Israel, to a readiness to accept Israel’s legitimate existence. Such a shift depended on their understanding that this promissory concession to Israel would bring what Palestinians “yearn for,” namely the freedom to govern themselves in peace and dignity. A win-win so obvious, that, as Gavin Esler of the BBC opined, “it could be solved with an email.”[32]

What the Oslo architects and their Western supporters so completely underestimated was the hold that his native honor-world held over Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) chairman Yasser Arafat. This lack of insight not only dominated thinking in Western circles (not put at risk by such a gamble), but even Israeli political and intelligence circles, who had much to lose:

[I]t is clear that it was not only Israel’s political leadership that was held hostage by the chimerical conception that an era of peace with the Palestinian Authority had begun: M[ilitary] I[ntelligence] and the Shin Bet security service had trouble liberating themselves from the same feeling. The intelligence officials were not always willing to let facts disturb a rosy perception of reality.[33]

Just because Western and Israeli analysts failed to pay attention, however, does not mean the laws of honor-shame ceased to operate. After the ceremonious signing of the deal on the White House lawn, PLO chairman Arafat found himself the target of immense hostility from his Arab and Muslim honor-group for having brought shame upon himself, his people, upon all Arabs and all Muslims. When he arrived in Gaza in July 1994, Hamas denounced him roundly: “His visit is shameful and humiliating, as it occurs in the shadow of occupation and in the shadow of Arafat’s humiliating submission before the enemy government and its will. It is impossible to present a defeat as victory.”[34] Edward Said, proud member of the Palestinian National Council, the PLO’s semi-parliament, echoed the language of Hamas: the compromises involved a humiliating and “degrading … act of obeisance … a capitulation” that produced a state of “supine abjectness … submitting shamefully to Israel.”[35] Thus did the “post-colonial” intellectual speak the zero-sum, tribal language of Arab and Muslim honor-shame, attacking negotiation as dishonorable; this was the very language Westerners avoided discussing lest they “Orientalize the Orient.”

And yet Arafat used the same honor-shame language in Arabic, from the moment the accords were signed and the Nobel Prize granted.[36] Six months after returning from Tunisia in July 1994, to what had, as a result of the accords, become Palestinian-controlled territory, Arafat defended his policy to fellow Muslims in South Africa, not by speaking of the “peace of the brave,”[37] but rather by invoking Muhammad’s Treaty of Hudaybiya, signed in weakness, broken in strength. To the extent that Arabs were sold on the Oslo process, it was as a Trojan horse, not as a (necessarily) humiliating concession; a plan for honorable war not for ignominious peace.[38] In cultures where, for honor’s sake, “what was taken by force must be retaken by force,” any negotiations are shameful and cowardly.[39]

By and large, Western journalists and policymakers, including the “peace camp” in Israel, and even intelligence services, ignored Arafat’s repeated invocations of Hudaybiya.[40] Advocates of peace viewed them as antics designed to appease public opinion (itself a thing worth pondering) and remained confident that, in the end, the more mature call of the international community would sway Arafat to the side of positive-sum reason. Practitioners of “peace journalism” in Israel, for example, consciously avoided such discouraging news items in general and the meaning of Hudaybiya in particular.[41] In his 800-page memoir on the Oslo failure, Dennis Ross, the U.S. Middle East envoy most deeply involved in negotiations with the Palestinian leadership, has not a word to say about the Hudaybiya controversy, despite how consistent it was with his own assessment of Arafat’s problematic behavior, his “failure to prepare his people for the compromises necessary for peace.”[42] Worse. Arafat’s sin was not of omission, but of commission: He systematically prepared his people for war right under the noses of the Israelis and the West.

Rather than consider the implications of this counter-evidence, those supporting the process attacked anyone who drew attention to them. The Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), a so-called Muslim civil rights organization with ties to the same Muslim Brotherhood of which Hamas is a branch, led the attack in the name of protecting the Prophet Muhammad’s reputation. Daniel Pipes wrote repeatedly about the Johannesburg mosque speech, the meaning of the Treaty of Hudaybiya, and the trouble Westerners found themselves in when they brought up the subject. Despite being studiously fair to the Muslim prophet on historical grounds, Pipes provoked furious condemnation and an early accusation of “Islamophobia.”[43]

The outcry essentially forbade critics from examining evidence relevant to their pressing concerns. Instead, peace enthusiasts viewed Arafat and the Palestinian leadership as full-fledged modern players who wanted their own nation and their freedom, and whom one could trust to keep commitments. Most thought that Arafat would, when the opportunity presented itself, choose the imperfect, positive-sum, win-win, over the zero-sum, all-or-nothing, win-lose. They “believed” in the Palestinian leadership and shamed anyone who dared to suggest the Palestinians still clung tightly to atavistic revenge. Thus, even as Jerusalem and Washington prepared for a grand finale to the peace process at Camp David in the summer of 2000; even as Israel’s media prepared their people for peace, Arafat’s media prepared Palestinians for war.[44] And none of the key decision-makers paid any attention.

The inability to understand the dynamics of maintaining honor (through fighting Israel) and avoiding shame (brought on by compromising with Israel) doomed Oslo to failure from the start. People involved, who thought that they were “so close” and that if only Israel had given more, it would have worked, got played.[45] For the Palestinian decision-makers, it was never close. Even a successful deal would have led to more war. Indeed, according to that logic, the better the deal for the Palestinians — i.e., the “weaker” the Israelis — the more aggression will accompany its implementation.[46]

In the aftermath of Arafat’s terror war (the “al-Aqsa Intifada”) in 2000, apologists made heroic efforts to interpret his behavior as rational, to ignore his deliberate planning of the terror war, and instead to blame Israel. Criticism of Arafat, especially for behavior characteristic of honor-shame cultures, elicited shouts of racism.

Once Oslo exploded, Westerners who clung to their fantasies continued to misunderstand subsequent events. In the aftermath of Arafat’s resounding but predictable “no” at Camp David in July 2000, and on several other occasions after the outbreak of his terror war (euphemized as the “al-Aqsa Intifada”) in late September, apologists made heroic efforts to interpret his behavior as rational, to ignore his deliberate planning of the terror war, and instead to blame Israel.[47]

As part of the counter-attack, criticism of Arafat, especially for behavior characteristic of honor-shame cultures, elicited shouts of racism. In an interview with Israeli academic Benny Morris, for example, former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak complained about systematic lying on Arafat’s part, which made every discussion a calculus between calling out lies or ignoring them and moving on at a disadvantage.[48]

These remarks incensed Middle East observers Hussein Agha and Robert Malley:

[Barak’s] words in the initial interview were unequivocal. “They are products of a culture in which to tell a lie … creates no dissonance,” he pronounced. “They don’t suffer from the problem of telling lies that exists in Judeo-Christian culture. Truth is seen as irrelevant.” And so on. But, plainly, factual accuracy and logical consistency are not what Morris and Barak are after. What matters is self-justification by someone who has chosen to make a career—and perhaps a comeback—through the vilification of an entire people.[49]

This is classic Edward Said: Attack the motives of your critics (often projection); claim moral injury at the insult, and in the process, distract attention from the accuracy of the Orientalist remarks. Though backed by hard evidence of extensive and fluent Palestinian use of open lies in the negotiations,[50] Barak’s charge becomes, in the hands of Arafat’s apologists, the “vilification of an entire people.”

The success of this ready use of what one might call the “racist card” has meant that the academic literature on lying in Arab culture, which should cover walls of bookshelves (at least in the libraries of our intelligence services), is seriously underdeveloped.[51] If Oslo failed, it was primarily because the Israelis and the Americans refused to believe that the Palestinians were lying to them — across the boards.

Ignoring the Ongoing Quest for the Caliphate

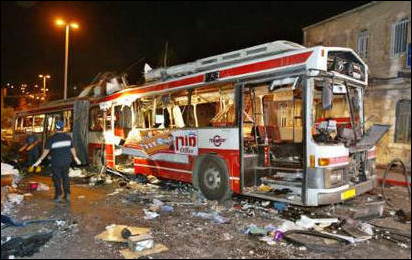

For this and many similar reasons, when the jihadists came out of the belly of the Oslo Horse in late September 2000, too many Westerners, eager to interpret the violence as the “desperation” of freedom fighters denied their rights, ignored the evidence that Arafat planned the war, [52] and instead, blamed Israel. As a result, many journalists and scholars who told their Western audiences that the “al-Aqsa Intifada” was a national-liberation uprising against occupation seemed to have had no idea, or if they did, chose not to speak of how, in the minds of many of these fighters, the “al-Aqsa intifada” launched a new phase of an apocalyptic global jihad, whose messianic goal was a worldwide caliphate, and for whom suicide terror was its newest and most potent weapon.[53] The indifferent, if not negative, response of the scholarly community to early studies in Hamas’s apocalyptic thought in the 1990s meant that the Western public sphere needed to wait until the second decade of the twenty-first century to find out that the global jihad that created a caliphate in substantial parts of Syria and Iraq and targeted infidels in their own countries, was driven by the same apocalyptic visions.[54] Indeed, it is still not clear to most observers how global jihadists exploited the “al-Aqsa Intifada” to fuel their own campaigns and recruitment.[55]

Recruits line up at a Hamas training camp. In the wake of the Lebanon war in 2006, scholars such as pacifist Judith Butler, welcomed Hamas and Hezbollah into the “global progressive left” as “comrades in the anti-imperialist struggle.”

So, instead of being wary of this new and violent religious imperialism and condemning jihad’s savage martyrdom operations, European journalists spread its anti-Zionist war propaganda as news while European progressives welcomed and cheered it on. Misinformed by media reports in April 2002 of the Israel Defense Forces’ supposed massacre in Jenin, Western protesters marched in the streets wearing mock suicide belts to show solidarity with Hamas “martyrs.”[56] In the wake of the Lebanon war in 2006, scholars such as the pacifist Judith Butler welcomed Hamas and Hezbollah into the “global progressive left” as “comrades in the anti-imperialist struggle.”[57] Thus did progressives, woefully uninformed, enthusiastically welcome a jihad that then struck at Israel, but now haunts the entire world, especially the Muslim world.

So blinded were Western information professionals—journalists, scholars, policy analysts, even translators—by their own post-colonial rhetoric, that they proved incapable of identifying the triumphalist Islam that gained steady momentum in its drive for a global caliphate in this generation and century. Or, if they did realize the presence of such imperialist Muslims, they refused to discuss them and attacked anyone who did. This prevailing attitude seriously damaged the West’s ability to distinguish between false moderates who want to reduce infidels the world over to dhimmitude[58] and moderates who truly want to live at peace with non-Muslims.

Almost everyone will agree that those jihadists who resort to the sword, such as al-Qaeda or ISIS (Islamic State), are not moderates. But what about those who stick to da’wa (summons to conversion), who work in nonviolent ways for the same ultimate goal of reestablishing the caliphate? When the Muslim Brotherhood’s Yusuf Qaradawi says that the “United States and Europe will be conquered not by jihad, but by da’wa,” does that make him a moderate?[59] What if the da’wa preacher is just playing the good cop to the jihadist bad cop? From the perspective of the millennial goal of a global caliphate, the difference between radical and “moderate” Islamists is less a matter of vision than timing, less a matter of differing goals than of differing tactics. Such connections, however, do not register on the radar screens of information professionals who observe Said’s anti-Orientalist strictures. Rather they urge us to see the two as clearly distinct.[60]

Such an approach, however, falls into a classic jihadist trap. When da’wa proponents of caliphate denounce al-Qaeda or ISIS for their violence, insisting that these jihadists have nothing to do with Islam, they do so as a deceptive cognitive war tactic. They know full well that the Islam they embrace is a religion of conquest.[61] They just do not want the Western “infidels,” their sworn enemies and targets, to acknowledge that implacable, imperialist hostility, at least as long as global jihad is militarily weak. Rather they want Western policymakers to renounce “Islamophobic” talk of world domination and, instead, appease Muslim grievances.[62]

And far too many Westerners have complied — from George W. Bush’s “Islam, religion of Peace” speech right after the 9/11 terror attacks,[63] to the Obama administration’s great efforts to ignore, deny, and euphemize anything redolent of Islamic violence,[64] to a long string of academics who should have hastened to correct the record after Bush’s rhetorical concession and instead went out of their way to underscore Islam’s peaceful nature.[65]

And things get progressively worse. The insistence on the basic sameness (the “common humanity”) of Arab/Muslim culture and Western culture (the “vast majority” of peaceful Muslims, the “vibrant civil societies” in Syria and Iraq) has gone from therapeutic experiment to dogmatic formula: To question it is racist and “Islamophobic.” Violators who discuss unpleasant things are punished, excluded, exiled. Indeed, so strong is the fear of the “Islamophobic” accusation that it has come to play the role of the sea serpents that strangled Laocoön when he tried to warn his fellow Trojans against the Greeks’ wooden horse.[66] British politicians, police, and journalists, for example, did nothing to protect thousands of girls from sexual exploitation for over a decade, in order to avoid being branded “Islamophobic.”[67]

Few incidents better illustrate this self-induced blindness and incompetence than the way Western information professionals handled the Arab uprisings of 2010-11. In a radical misreading of the popular and social-media empowered protests that drove some Arab dictators from their perches, scholars interpreted the uprisings in light of European democratic revolutions: the “Spring of Nations” of 1848 and the liberation of Eastern Europe and Russia in 1989.[68] Systematically dismissing the danger of the Muslim Brotherhood taking power in democratic elections, commentators and policymakers urged support for the Islamist movement, seen by post-colonial information professionals as their mirror image, their comrade in arms.[69] If pre-Said, “Orientalists” had (supposedly) seen only the bad they projected, then after him, post-Orientalists could see only the good they projected.

This politically correct approach even infected U.S. intelligence services. In February 2011, just when the Obama administration was making crucial (and misguided) decisions on how to deal with the Egyptian crisis, James Clapper, director of National Intelligence, testified with the following astonishing assessment to Congress (which he quickly walked back):

The term “Muslim Brotherhood” … is an umbrella term for a variety of movements, in the case of Egypt, a very heterogeneous group, largely secular, which has eschewed violence and has decried Al Qaeda as a perversion of Islam.[70]

It is hard to catalogue the misconceptions involved in this astonishingly foolish statement. It bespeaks a lack of understanding of triumphalist religious behavior and a superficial application of inappropriate terminology that leaves the observer wondering whether this was a deliberate act of misinformation or a genuine product of U.S. intelligence gathering and assessment.

It is also hard to separate this utterly disoriented operative assessment from the academic discussion underpinning it, largely influenced by the penitential paradigm Said urged on the West. Here Western dupes are to interpret nonviolence as a sign of Muslim moderation and attribute Muslim violence to Western provocation; here we are to assume that when Muslims denounce violence, then they are with “us” and not with “them,” that they do not share the jihadist goal of a worldwide caliphate. Rather than carry on about an enemy aspiring to world dominion, Islamists urge the West to address Muslims’ sense of powerlessness by empowering them.[71]

The results of this blind disregard for the reality on the ground — the power of honor-driven religious movements; the variable calculus of violence when feeling weak or strong; the responses to perceived weakness and lack of resolve on the enemies’ part[72] meant that what Western thought leaders believed to be a democratic spring, which they eagerly welcomed, was actually springtime for tribal and apocalyptic warfare: Oslo jihad redux, on a massive scale.[73] A generational, cataclysmic, “thirty-year war” that is just beginning. Where the West intervened (Libya, Egypt), it backfired, and where it did not (Syria), it exploded. And as millions of refugees are thrown up on the shores of Europe by these upheavals, Western policymakers remain captive to suicidal memes (“we can’t just refuse them entry”) that bespeak a profound ignorance of Arab and Muslim culture — those fleeing, those making them flee, and those with the power but not the desire to address this meltdown of their societies under the blows of the caliphate.

Conclusion

Through the backdoor of an unreciprocated concern for the “other,” educated Westerners have allowed a hostile, bullying, honor-shame discourse to take over much of their public space: “Islamophobia,” not Islamism, is the problem;[74] Palestinians continue to save face and regain public honor by besmirching Israel, which, by its very existence and success, shames them; while so many social justice warriors, consumed with post-colonial guilt and fearful of the “Islamophobic” label, join forces with the “honor-brigade” in driving Israel beyond the pale.[75]

In the larger picture of civilizational development, this is lamentable. It took a millennium of constant and painful efforts for Western culture to learn how to sublimate man’s libido dominandi to the point of creating a society tolerant of diversity, one that resolved disputes with a discourse of fairness rather than violence, and one where positive-sum encounters are a desired norm. To insist, as many liberals do, that this exceptional achievement be considered the default mode for mankind regardless of how far the “other” is from this cherished goal, and to exempt enemies of democracy from the civic responsibility of self-criticism even while redoubling its burden on oneself, is to undermine the freedoms Western civilization has built up over centuries.[76]

Unless and until academics and information professionals reclaim and till fields like honor-shame dynamics and Islamist triumphalism, Westerners will not be able to understand Arab and Islamic societies and will continue to indict the critic, not the legitimate target of criticism, at great peril to their democratic values and national interests. The inability to engage in self-criticism is the greatest weakness of honor-shame cultures, and the ability to do so is the greatest strength of those committed to integrity. Yet, now, astonishingly, the inability is strength, and our over-eagerness to compensate, our weakness.

Richard Landes is a medieval historian currently writing a book provisionally entitled, “They’re So Smart Cause We’re So Stupid: A Medievalist Guide to the 21st Century”. He lives in Jerusalem and blogs at The Augean Stables.

![]()

Notes:

[1] Edward Said, Orientalism (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978), quotes from New York: Vintage, 1994 ed.

[2] See, for example, Efraim Karsh, “How the Oslo Process Doomed Peace,” Middle East Quarterly, Fall 2016.

[3] See, for example, “SPLC publishes media guide to countering prominent anti-Muslim extremists,” Southern Poverty Law Center, Montgomery, Ala., Oct. 26, 2016.

[4] On Arab honor-shame dynamics, see Raphael Patai, The Arab Mind (Tucson Ariz.: Recovery Resources Press, 1989, 2007); David Pryce Jones, Closed Circle: An Interpretation of the Arabs (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1987, 2002).

[5] On honor-shame dynamics, see Christopher Boehm, Blood Revenge (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984); Frank Henderson Stewart, Honor (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994); James Bowman, Honor: A History (New York: Encounter Books, 2007).

[6] Talib Kafaji, The Psychology of the Arab: The Influences that Shape an Arab Life (Bloomington, Ind.: Author House, 2011), p. 75. See, also, Nadine Naber, Arab America: Gender, Cultural Politics, and Activism (New York: New York University Press, 2012), pp. 99-109 Nonie Darwish, Cruel and Usual Punishment (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2008), Part II, chap. 2.

[7] Pryce-Jones, Closed Circle, chap. 2.

[8] On the fundamental role of envy, see Wilhelm Schoeck, Envy: A Theory of Social Behavior (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1987).

[9] Gideon Kressel, Ascendency through Aggression: The Anatomy of Blood Feud among Urbanized Bedouins (Weisbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1996).

[10] Landes, “Triumphalist Religiosity: The Unanticipated Problem of the 21st Century,” Tablet Magazine, Feb. 10, 2016.

[11] Marcel Simon, Verus Israel: Study of the Relations between Christian and Jews in the Roman Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), chap. 4.

[12] Efraim Karsh, Islamic Imperialism: A History (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2nd ed., 2013).

[13] Landes, “Why the Arab World Is Lost in an Emotional Nakba,” Tablet Magazine, June 24, 2014.

[14] See, for example, Brian Whitacker, “Its Best Use Is as a Doorstop,” The Guardian (London), May 24, 2004, review of the re-edition of Raphael Patai’s The Arab Mind.

[15] Richard Landes, “Edward Said and the Culture of Honour and Shame: Orientalism and Our Misperceptions of the Arab-Israeli Conflict,” Israel Affairs, Oct. 2007, pp. 844-58.

[16] Herbert S. Lewis, “The Influence of Edward Said on Anthropology or, Can the Anthropologist Speak?” Israel Affairs, Oct. 2007, pp. 774-85.

[17] Robert Irwin, Lust for Knowing: The Orientalists and their Enemies (New York: Allen Lane, 2006), p. 4; Ibn Warraq, Defending the West (Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 2007); Joshua Muravchik, David into Goliath: How the World Turned against Israel (New York: Encounter Books, 2014), chap. 7.

[18] Said, Orientalism, p. 204. See also Matthieu Coureville’s treatment of this oft-cited assertion, Edward Said’s Rhetoric of the Secular (London: Continuum, 2010), pp. 59-61.

[19] Said, Orientalism, p. 323.

[20] Ibid., p. 346.

[21] Ibid., p. 345.

[22] “The Truth that Palestinians Are Afraid to Tell You,” You Tube, accessed Oct. 17, 2016.

[23] Bruce Bawer, Surrender: Appeasing Islam, Sacrificing Freedom (New York: Doubleday, 2007), pp. 61-174.

[24] Said, Orientalism, p. 336; Anthony Kwame Appiah, The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen (New York: Norton, 2011), pp. 19-20.

[25] Said, Orientalism, p. 27.

[26] Said, Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World (New York: Vintage, 1997), p. xiv.

[27] The editor at Holt, who had commissioned, but then refused Benny Morris’ 1948 did so, among other reasons, because his depiction of the “Arab leadership’s corruption, incompetence, and disunity” was “racist.” Email exchange, published with permission.

[28] Martin Kramer, Ivory Towers on Sand (Washington: Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2001), chap. 4.

[29] Gerald Steinberg, “Postcolonial Theory and the Ideology of Peace Studies,” Israel Affairs, Oct. 2007, pp. 786-9.

[30] On the therapeutic fallacy, Anthony Kwame Appiah, “Europe upside down: Fallacies of the new Afrocentrism,” Times Literary Supplement, Feb. 12, 1993. On the critique of the “clash,” Amartya Sen, “What Clash of Civilizations?” Slate, Mar. 29, 2006.

[31] On Arab political culture, see, Lee Smith, Strong Horse: Power, Politics, and the Clash of Arab Civilizations (New York: Doubleday, 2010). On Muslim culture’s problems with social and gender equality, see Bernard Lewis, What Went Wrong? The Clash between Islam and Modernity in the Middle East (New York: Harper-Collins, 2003), chap. 4. On Arab culture at the turn of the millennium, see the United Nations’ Arab Human Development Report (2002).

[32] Gavin Esler, BBC Dateline London. On the logic of Oslo, see Ofira Seliktar, Doomed to Failure? The Politics and Intelligence of the Oslo Peace Process (Oxford: Praeger Security International, 2009), pp. 7-49; Efraim Karsh, Arafat’s War: The Man and His Battle for Israeli Conquest (New York: Grove, 2003), chap. 7. On the role of progressive peace and conflict studies in formulating it, see Steinberg, “Postcolonial Theory and the Ideology of Peace Studies.”

[33] Yossi Melman, “Don’t Confuse Us with Facts,” Haaretz (Tel Aviv), Aug. 16, 2002. See, also, Kenneth Levin, The Oslo Syndrome: Delusions of a People under Siege (Hanover, N.H.: Smith and Kraus, 2005), pp. 343-57.

[34] Stephen J. Sosebee, “Yasser Arafat’s Return: New Beginning for Palestine,” Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, Sept./Oct. 1994.

[35] Said, “The Morning After,” London Review of Books, Oct. 21, 1993.

[36] Efraim Karsh, “Arafat’s Grand Strategy,” Middle East Quarterly, Spring 2004.

[37] Yasser Arafat, “Nobel Lecture,” 1994, Nobelprize.org, accessed Oct. 17, 2016.

[38] Faisal Husseini, al-Arabi (Cairo), June 24, 2001, in Special Dispatch No. 236, Middle East Media Research Institute, Washington, D.C., July 6, 2001.

[39] See “Slogan on the wall behind al-Durahs,” The Augean Stables, Oct. 31, 2016.

[40] Melman, “Don’t Confuse Us with Facts“; idem, “Wild Card,” Haaretz, Aug. 9, 2002.

[41] See, for example, Gadi Wolfsfeld, The Media and the Path to Peace (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), pp. 38-42.

[42] Dennis Ross, The Missing Peace: Inside Story of the Fight for Middle East Peace (New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2004), pp. 767-69, 776. See, also, Charles Enderlin, Shattered Dreams: The Failure of the Peace Process in the Middle East (New York: Other Press, 2002), pp. 5-41.

[43] Daniel Pipes, “Lessons from the Prophet Muhammad’s Diplomacy,” Middle East Quarterly, Sept. 1999; idem, “Arafat and the Treaty of Hudaybiya,” Sept. 10, 1999; idem, “How Dare You Defame Islam?” Commentary, Nov. 1999; idem, “Do I Win a British ‘Islamophobia’ Award?” Lion’s Den, June 26, 2004, updated Mar. 28, 2016.

[44] Itamar Marcus, “Rape Murder, Violence, and War for Allah against the Jews: Summer 2000 on Palestinian Television,” Palestinian Media Watch, Jerusalem, Sept. 11, 2000.

[45] Golan Lahat, Hapitui Hameshihi: Aliyato Unefilato shel Hasmol Haisraeli (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 972 series, 2004).

[46] Joel Fishman, “The Delusions of Oslo in the Service of Disengagement,” Makor Rishon (Jerusalem), Aug. 20, 2004; Seliktar, Doomed to Failure?; Raphael Israeli, The Oslo Idea: The Euphoria of Failure (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 2012).

[47] Deborah Sontag, “And Yet So Far: A Special Report: Quest for Mideast Peace: How and Why It Failed,” The New York Times, July 26, 2001; Richard Falk, “Ending the Death Dance,” Nation Magazine, Apr. 11, 2002; Robert Wright, “Was Arafat the Problem?” Slate Magazine, Apr. 18, 2002.

[48] Benny Morris, “Camp David and After: An Exchange (1. An Interview with Ehud Barak),” The New York Review of Books, June 13, 2002.

[49] Benny Morris and Ehud Barak, reply by Robert Malley and Hussein Agha, “Camp David and After—Continued,” The New York Review of Books, June 27, 2002.

[50] Karsh, Arafat’s War, chap. 9-11; Seliktar, Doomed to Failure? p. 165.

[51] On Said’s use of the “racism card,” see David Shipler, “From a Wellspring of Bitterness,” review of Said’s The Politics of Dispossession,” The New York Times, June 26, 1994. See, also, Peter Naaffsinger, “‘Face’ among Arabs,” Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, D.C., Sept. 18, 1995; Talib Kafaji, The Psychology of the Arab, p. 57.

[52] Itamar Marcus and Nan Zilberdik, “Arafat planned and led the Intifada: Testimonies from PA leaders and others,” Palestinian Media Watch, Nov. 28, 2011; Jonathan Dahoach-Halevy, “The Palestinian Authority’s Responsibility for the Outbreak of the Second Intifada: Its Own Damning Testimony,” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, Feb. 20, 2013.

[53] Safar Ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Hawali, “The Day of Wrath: Is the Intifadha of Rajab only the Beginning?” Azzam.com, Sept. 11, 2001; Anne-Marie Oliver and Paul Steinberg, The Road to Martyrs’ Square: A Journey into the World of the Suicide Bomber (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005); Reuven Paz, “Hotwiring the Apocalypse: Apocalyptic Elements of Global Jihadi Doctrines,” in Suicide Bombers: The Psychological, Religious and Other Imperatives, Mary Sharpe, ed. (Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2008), pp. 103-18.

[54] Jean-Pierre Filiu, Apocalypse in Islam (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011); William McCants, The ISIS Apocalypse: The History, Strategy, and Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State (New York: Saint Martin’s Press, 2015), pp. 69-200; Jessica Stern and J.M. Berger, ISIS: The State of Terror (New York: HarperCollins, 2015), pp. 218-53; Graeme Wood, “What ISIS Really Wants,” The Atlantic, Mar. 2015.

[55] Richard Landes, “The Wages of Moral Schadenfreude in the Press: Anti-Zionism and European Jihad,” in From Antisemitism to Anti-Zionism: The Past and Present of a Lethal Ideology, Eunice G. Pollack, ed. (Brighton Mass.: Academic Studies Press, 2017).

[56] Oriana Fallaci, “On Jew-Hatred in Europe,” Panorama Magazine, Apr. 17, 2002; Patrick Cockburn, The Age of Jihad: Islamic State and the Great War for the Middle East (London: Verso, 2016).

[57] “Judith Butler on Hamas, Hezbollah & the Israel Lobby,” Radical Archives, Sept. 7, 2006.

[58] Daniel Pipes, “The Islamic States of America?” FrontPageMagazine, Sept. 30, 2004. On dhimmitude, see Antoine Fattal, Le statut légal des non-musulmans en pays d’Islam (Beirut: Librairie Orientale, 1986); Bat-Ye’or, Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide (Madison, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2001).

[59] Sheik Yousuf al-Qaradawi, “Islam’s ‘Conquest of Rome’ Will Save Europe from Its Subjugation to Materialism and Promiscuity,” Qatar TV, July 28, 2007, Middle East Media Research Institute, Washington.

[60] “Pas d’amalgame: Critique et contre-critique,” Contrepoints (Paris), Nov. 2015.

[61] “How Islam will dominate the world,” Duaat, Mar. 10, 2008.

[62] Suggested, for example, by Jeffry R. Halverson, R. Bennett Furlow, Steven R. Corman, “How Islamist Extremists Quote the Qur’an,” Arizona State University Center for Strategic Communications, report no. 1202, July 9, 2012.

[63] George W. Bush, remarks at Islamic Center of Washington, D.C., Sept. 17, 2001.

[64] Daniel Pipes, “Denying Islam’s Role in Terror: Explaining the Denial,” Middle East Quarterly, Spring 2013; Teri Blumenfeld, “Denying Islam’s Role in Terror: Problems in the FBI,” Middle East Quarterly, Spring 2013; David J. Rusin, “Denying Islam’s Role in Terror: Problems in the U.S. Military,” Middle East Quarterly, Spring 2013; David Frum, “Why Obama Won’t Talk about Islamic Terrorism,” The Atlantic, Feb. 2015.

[65] See, for example, John Esposito, Islam the Straight Path (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991); see also John Burger, “Islam: Religion of Peace or Font of Terror? A conversation with John Esposito of the Georgetown Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding,” Aleteia, Jan. 21, 2015; Karen Armstrong, Muhammad: A Prophet for Our Time (New York: Harper Collins, 2006), chap. 5; Juan Cole, Engaging the Muslim World (New York: Saint Martin’s Press, 2009), pp. 41-82. For a critique, see Martin Kramer, Ivory Towers on Sand (Washington: Washington Institute of Near East Policy, 2001), chap. 3; Kramer, The War on Error: Israel, Islam, and the Middle East (New York: Transaction Publishers, 2016).

[66] Paul Marshall and Nina Shea, Silenced: How Blasphemy and Apostasy Codes Are Choking Freedom Worldwide (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 173-286.

[67] Peter McLoughlin, Easy Meat: Inside Britain’s Grooming Scandal (London: New English Review, 2016).

[68] Shadi Hamid, “The Struggle for Middle East Democracy,” Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C., Apr. 26, 2011.

[69] Steven Brooke, “U.S. Policy and the Muslim Brotherhood,” in The West and the Muslim Brotherhood after the Arab Spring, Lorenzo Vidino, ed. (Dubai: Al-Mesbar Studies and Research Center and The Foreign Policy Research Institute, 2013), pp. 6-31.

[70] Sergio Fabbrini and Amr Yossef, “Obama’s wavering: US foreign policy on the Egyptian crisis, 2011–13,” Contemporary Arab Affairs, 8:1 (2015): 65-8.

[71] See, for example, Brooke, “U.S. Policy and the Muslim Brotherhood,” pp. 18-21; Halverson et al, “How Islamist Extremists Quote the Qur’an.”

[72] See, for example, Andrew McCarthy, Willful Blindness: A Memoir of Jihad (New York: Encounter Books, 2008); idem, See Something, Say Nothing: A Homeland Security Officer Exposes the Government’s Submission to Jihad (Washington D.C.: WND Books, 2016).

[73] Asaf Maliach, “Bin Ladin, Palestine and al-Qa’ida’s Operational Strategy,” Middle Eastern Studies, May, 2008, pp. 353-75.

[74] Juan Cole, “Islamophobia as a Social Problem: 2006 Presidential Address,” Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, June 2007, pp. 3-7.

[75] Asra Nomani, “Meet the honor brigade, an organized campaign to silence debate on Islam,” The Washington Post, Jan. 16, 2015; Robin Shepherd, A State beyond the Pale: Europe’s Problem with Israel (London: Weidenfeld and Nickolson, 2009).

[76] This problem has variously been called the “human rights complex”: Charles Jacobs, “Why Israel and not Sudan, is Singled Out,” Boston Globe, Oct. 5, 2002; and “humanitarian racism”: Manfred Gerstenfeld, “Beware the Humanitarian Racist,” Ynet, Jan. 23, 2012. Such attitudes can lead to “anti-racist racism”: Douglas Murray, “The New Anti-racist Racists,” Gatestone, Oct. 28, 2016.

RSS

RSS

Latest Comments

Hello Mike, Thank you for your positive feedback to the article. I felt there wasn’t too much critical analysis of ...

Thanks for this considered and well constructed article. A follow up article on the manner in which the editorial contro...

THE CLUELESSNESS OF CLAIMING THAT OBAMA'S MIDDLE EAST POLICIES WERE A FAILURE CANNOT BE FURTHER FROM THE TRUTH, WHAT THE...

As long as Obama is the president of the usa do not trust the us government......

Thank you for an good read....