![]()

Mon, May 25, 2012 | By Gareth H. Jenkins

This article was first published in the Turkey Analyst, vol. 5 no. 13 (www.turkeyanalyst.org), a biweekly publication of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center. © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center, 2012.

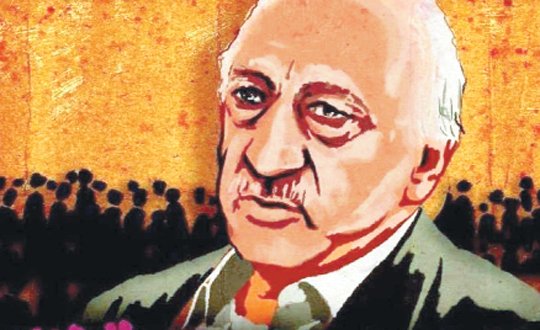

On June 14, 2012, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan publicly invited Fethullah Gülen, the leader of the powerful Gülen Movement, to return to Turkey from self-imposed exile in the United States. On June 16, 2012, in a videoed interview, Gülen declined the invitation, breaking down in tears as he expressed his fears that his return could be exploited to destabilize the country and damage his movement’s achievements. In recent months, Erdoğan and members of the Gülen Movement have been engaged in a bitter power struggle. As a result, Erdoğan’s invitation to Gülen was interpreted by some commentators as a reconciliatory peace offering. However, it would probably be more accurate to interpret it as a challenge to Gülen, an assertion of authority in the guise of a magnanimous gesture.

Background

Relations between Erdoğan and the Gülen Movement have always been strained. Before the foundation of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2001, Gülen’s supporters had tended to align themselves with the conservative wings of center-right parties rather than the string of explicitly Islamist parties established by Necmettin Erbakan (1926-2011). One of the reasons was theological. Initially, Erbakan’s parties built their political support base on the networks of the Sufi brotherhoods known as tariqah, particularly the Naqshbandi brotherhood. Erdoğan also comes from a Naqshbandi background.

The Naqshbandis believe that, in addition to the exoteric message of the Quran and the hadith, the Prophet Muhammad instructed some of his close associates in an esoteric tradition, which has been orally transmitted by initiates down to the present day. Neither Gülen (born 1941) nor his spiritual mentor Said Nursi (1876–1960) were initiated into this tradition. As a result, the Naqshbandi have always looked down on Gülen, arguing that his theological musings lack spiritual legitimacy and intellectual depth; while Gülen Movement has long regarded the tariqah networks as rivals and obstacles to its own efforts to develop a social support base.

During the late 1990s, the fiercely secularist Turkish military orchestrated a sustained campaign of pressure against the country’s Islamist movements, which has become known as the “28 February Process” after the date in 1997 when it delivered an ultimatum to a coalition government led by Erbakan. Erbakan was subsequently forced to resign, and in 1998, he was banned from politics for five years and his Welfare Party (RP) outlawed. In 1999, as the pressure on Islamists continued, Gülen fled into exile in the United States.

The 28 February Process gave the Gülen Movement a common cause with the former members of Erbakan’s parties — such as Erdoğan — who founded the AKP. It mobilized its network of NGOs, businesses and media outlets on the AKP’s behalf, and members of the movement successfully ran for parliament on the AKP ticket in the November 2002 general election that brought the party to power. Initially, both Erdoğan and the Gülen Movement proceeded cautiously. However, as they grew in confidence, Gülen sympathizers in the judiciary and the media served as the main driving force behind a series of highly politicized judicial investigations — including the notorious Ergenekon and Sledgehammer cases — which resulted in the imprisonment of hundreds of perceived opponents of the AKP and the Gülen Movement, and the intimidation into silence of many thousands more.

Although he was not actively driving them, the cases strengthened Erdoğan by muffling many of his critics. But his relationship with the Gülen Movement was always primarily an alliance of convenience and began to break down as Erdoğan started to make plans to replace Turkey’s parliamentary system with a presidential one and then have himself elected president for two successive five-year terms.

In the general election of June 12, 2011, the AKP was reelected to a third successive term in office, winning nearly twice as much of the vote as its nearest rival; and arguably leaving the Gülen Movement as the only force capable of blocking Erdoğan’s presidential ambitions. The movement feared that any further increase in Erdoğan’s power would be accompanied by a commensurate loss in its own influence — particularly in its ability to appoint its sympathizers to key positions in the state apparatus, such as the police and the judiciary.

As a result, as tensions between Erdoğan and Gülen Movement intensified through late 2011 and early 2012, any ideological or theological considerations had become secondary to a simple struggle for power.

Implications

The breaking point occurred on February 7, 2012, when an Istanbul public prosecutor, Sadrettin Sarıkaya, issued a summons to Hakan Fidan, the head of the National Intelligence Organization (MİT) and an Erdoğan loyalist, on suspicion of collaborating with the militant Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The incident galvanized Erdoğan into action. He rushed a law through parliament, making any judicial action against the head of MİT dependent on prime ministerial approval. Sarıkaya was dismissed and dozens of suspected Gülen sympathizers in the Istanbul police were marginalized by being assigned to new posts. (See 5 March 2012 Turkey Analyst)

The purges continued over the months that followed. AKP officials close to Erdoğan began to publicly discuss abolishing the system of “Specially Authorized” prosecutors and courts, which have been responsible for politicized cases such as Ergenekon and Sledgehammer and which are one of the main clusters of Gülenist influence within the judicial system. On June 13, 2012, the Supreme Board of Judges and Prosecutors (HSYK), which oversees judicial appointments, announced a massive shakeup of the judicial personnel. A total of 2,335 judges and prosecutors were reassigned and several suspected Gülen sympathizers were removed from the politicized cases being handled by the Specially Authorized Courts.

The purges triggered an unprecedented stream of invective against Erdoğan in the Gülen Movement’s media organs. They also meant that, when Erdoğan called on Gülen to return to Turkey he probably believed that he was doing so from a position of strength.

It is unclear whether Erdoğan’s invitation — which was announced at a Turkish language festival organized by the Gülen Movement — was premeditated or whether it was spontaneous. Whatever the reason, it was an astute move. Although Gülen appears to be in relatively good health, he has never made any secret of his desire to be buried in Turkey. By issuing his invitation, Erdoğan was able to refute critics who had claimed that he feared and had been trying to prevent Gülen’s return while simultaneously making it impossible for him to accept.

In a society which still sets great store on etiquette, if he had accepted the invitation, it would have been very difficult for Gülen to have returned and opposed Erdoğan without appearing churlishly ungrateful — something which would have seriously damaged his public reputation. As a result, the public invitation effectively gave Gülen the choice between remaining in exile and putting himself forever in Erdoğan’s debt.

As was clear from his tearful response, Gülen was also aware that accepting the invitation would leave him very exposed. Although he would be unlikely to come to physical harm, it would be much easier for Erdoğan to restrict Gülen’s interactions with his followers and damage his reputation if Gülen was in Turkey rather than the United States.

However, even if there is no indication that it formed part of Gülen’s calculations, there is little doubt that remaining in the United States will enhance rather than diminish the cultish adulation with which he is regarded by many of his followers. Gülen’s appeal has always been emotional rather than intellectual; his writings characterized by a haze of good intentions rather than crisp, coherent argument. The portrayal by his followers of his exile in the United States as being self-sacrificing rather than self-serving has added another dimension to his image as a lifelong bachelor who has rejected material comforts in order to devote himself to God and the Prophet Muhammad. Gülen’s physical isolation in the woods of rural Pennsylvania has also shifted focus from his person to his persona — while simultaneously allowing him to distance himself from the more nefarious activities of some of his followers, such as their involvement in highly politicized court cases and the smear campaigns run by the movement’s media organs against its critics. It would be very difficult for Gülen to maintain a perceived distance from such activities if he was physically present in Turkey.

Conclusions

Far from representing an offer of reconciliation, Erdoğan’s invitation appears to be another move in his power struggle with the Gülen Movement. For the moment, it is a contest which Erdoğan is winning. The ferocity of many of the recent attacks on him in the Gülen media appear indicative of frustration at their inability to halt the purges of their followers; and fear that the erosion of their influence in the apparatus of state will intensify if Erdoğan succeeds in having himself elected to the presidency.

By inviting Gülen back to Turkey, Erdoğan gave him the choice between declining or returning and having his room for maneuver severely constrained; and thus effectively prevented Gülen from coming back and actively challenging Erdoğan’s grip on power. But, in the longer term, although it may be difficult for him personally, Gülen’s continued exile will help preserve the mystique with which he is regarded by his followers.

The Gülen Movement remains willfully opaque. The decision-making processes within the movement are unclear, although Gülen appears to restrict himself to announcing broad strategic goals rather than becoming involved in their detailed implementation. In many instances, individuals and groups of activists appear to enjoy considerable autonomy. Nevertheless, if Gülen was to return to Turkey it would be very difficult for him not to become more involved in the day to day running of the organization — not least because he would be much more accessible for advice and consultation. As a result, Gülen’s continued exile in the United States appears likely to ensure his persona rather than his person remains the movement’s main unifying force — and will thus make it easier to manage the transition when, eventually, Gülen dies.

Even though Erdoğan is currently winning the power struggle with the Gülen Movement, it would be a mistake to assume that his victory is assured. The Gülen Movement owes much of its success to the fact that it has always played for the long-term, spending years recruiting young people and building up its grassroots support. Even if Erdoğan’s purges have reduced its influence in the apparatus of state, it still controls a vast network in Turkish society.

Gareth Jenkins, a Nonresident Senior Fellow with the CACI & SRSP Joint Center, is an Istanbul-based writer and specialist of Turkish Affairs.

RSS

RSS

Latest Comments

Hello Mike, Thank you for your positive feedback to the article. I felt there wasn’t too much critical analysis of ...

Thanks for this considered and well constructed article. A follow up article on the manner in which the editorial contro...

THE CLUELESSNESS OF CLAIMING THAT OBAMA'S MIDDLE EAST POLICIES WERE A FAILURE CANNOT BE FURTHER FROM THE TRUTH, WHAT THE...

As long as Obama is the president of the usa do not trust the us government......

Thank you for an good read....