![]()

Winter 2014 | ITIC

This study is originally published by The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center. The study is an overall analysis of ISIS, also known as ISIL, Islamic State (or IS). The study is structured in nine sections,[1] which if read in conjunction with each other, draws a complete picture of ISIS. You can also download the study in PDF format here.

Overview

ISIS is making an effort to establish itself in the provinces in eastern and northern Syria and to expand its control at the expense of its many rivals, among them the Syrian Army, rebel organizations, the Al-Nusra Front and the Kurdish militias (YPG). It captured the Al-Tabqa military airfield in Al-Raqqah province and is now waging a campaign to conquer the city of Ayn al-Arab (Kobanî in Kurdish) near the Turkish border. At the same time, ISIS is investing considerable effort in building the government institutions of the self-declared Caliphate State. ISIS’s military achievements in Iraq in the summer of 2014 strengthened its position in eastern and northern Syria. In practice, they have created a supranational control zone in the territory of the two countries, where ISIS has established its control at the expense of its rivals.

Unlike the foothold it has gained in eastern and northern Syria, ISIS has relatively little presence in the rural areas around Damascus. It also has no significant presence in southern Syria or the Golan Heights. The dominant power in those areas is its rival, the Al-Nusra Front, which was ousted by ISIS from eastern and northern Syria and has established a firm foothold in southern Syria, including the Syrian Golan Heights. Unlike ISIS, in both locations the Al-Nusra Front cooperates with the other rebel organizations.

In the areas under its control where it established the Islamic State, ISIS has established a governmental infrastructure and is brutally imposing Islamic religious law on the local population (even at the expense of friction with the local population, the Al-Nusra Front and the other rebel organizations). ISIS also operates the parts of the state infrastructure that fell into its hands, including oil fields, which are an important source of income and help it meet the needs of the local population and establish its control. To operate the government infrastructure, ISIS utilizes existing personnel who served the Syrian regime. However, the shortage of skilled personnel has led ISIS to recruit qualified professionals from among the foreign fighters. In early July 2014, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi issued a call for scientists, judges, doctors and skilled military and administrative professionals to join the ranks of the Islamic State (Al-monitor.com).

So far, it seems that the Islamic State government mechanism in the Sunni areas of eastern Syria and western Iraq is a success. The local population recognizes the Islamic State as is capable of carrying out administrative and security functions, providing essential services, imposing law and order and carrying out with the duties of the state authorities of Syria and Iraq, perceived as corrupt and no longer functioning, with relative success.

Al-Raqqah: ISIS’s “capital city” in Syria

Overview

Al-Raqqah is an important city in northern Syria, the sixth largest in the country, which had a population of about 220,000 until the civil war. It served as the summer capital of the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mansur. Built in 722 AD, it was called Al-Rafiqa, and was located near the city of Al-Raqqah. The capital Al-Rafiqa soon became part of the city of Al-Raqqah, which kept expanding. Between 796 AD and 808 AD, it served as Abbasid Caliph Haroun al-Rashid’s summer capital, and towards the end of his life resided there. Thus the city has symbolic significance for the Islamic State, although it is of lesser importance than Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate and the symbol of its glory.

Since the ISIS occupation of Al-Raqqah tens of thousands of civilians have fled (including most of its Christian population), their numbers increasing significantly after the start of US air strikes on ISIS. In March 2013 the Syrian regime lost control of Al-Raqqah to the rebel. After the break with the Al-Nusra Front, ISIS invested great efforts in taking control over the city, as part of its plan to consolidate its control over eastern and northern Syria. During the process, which took several months, ISIS neutralized the power of the Al-Nusra Front and other rebel organizations and supporters of the Syrian regime. At the same time, it began to impose the rigid code of Islamic law on the local citizens.

The city charter

ISIS attaches great importance to establishing its control over the city of Al-Raqqah, its “capital city” in Syria. In September 2014, ISIS issued a document in Al-Raqqah called “The city charter” (wathiqat al-madina). ISIS issued a similar document in Mosul, Iraq, immediately after it was occupied. The document is intended to define the foundations of Islamic law (Sharia) that are binding for ISIS and the local population and to regulate the relationship between ISIS and the residents. The governmental entities set up by ISIS in the city of Al-Raqqah are supposed to be conducted according to the principles of the charter.

Below are the main points of the document (Syriahr.com, September 13, 2014):

- ISIS operatives are defined as “soldiers of the Islamic State” who took it upon themselves “to restore the glory of the Islamic Caliphate and eliminate the oppression and injustice of our fellow Muslims.”

- The attitude towards the residents will be determined by their behavior (“the secrets of their hearts we leave to Allah”). The charter states that “a person who is a Muslim from the outside, and is not involved in even one thing that contradicts Islam, will be treated by us as a Muslim. We will not suspect a man and will not accuse him without decisive proof and an overwhelming allegation […]”

- Residents living under the rule of the Islamic State will feel safe and secure because the Islamic regime guarantees the rights of the people under its protection and takes care of the oppressed.

- All public funds which belonged to the Syrian regime will be returned to the “state coffers” (i.e., the coffers of ISIS, which controls the Islamic State). The Caliph of the Muslims (i.e., Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi) is the one who will manage the funds “according to the needs of the Muslims.” Anyone who steals that money will be tried before the Sharia legal system and his hand will be cut off.

- It is forbidden to trade in wine, drugs, cigarettes, and “other forbidden things” or to become addicted to them.

- Residents are warned not to collaborate with the enemy, and in particular with the Syrian regime and “idol worshippers” (Bashar al-Assad’s government is called by the derogatory nickname “the Safavid government,” after a Shiite dynasty in the 16th century). Anyone who repents will be forgiven (“the gate of repentance is open to those who wish to pass through it”), but as for those “who insist and continue to withdraw from the religion of Islam, there is one sentence for them: death.”

- Desecration of graves and statues: “Our position regarding the holy graves […] and places of pilgrimage of the idol worshippers is according to the correct words of the Prophet Muhammad […]” The document cites a tradition (hadith) attributed to the Prophet Muhammad whereby graves and statues perceived as idol worship must be destroyed.

- Modesty of women: The charter calls on “respectable women” to “adhere to humility, scarves, and coverings.” They are to stay at home, “shut themselves away in the women’s courtyard,” and not leave it unless necessary, because “this was the way of the mothers of the faithful friends of the Prophet […]”

- The charter ends with a call to abandon the secular regime and adhere to the Islamic regime: “O people, you have tried the secular regimes and have gone through the periods of the monarchy, the republic, the Ba‘athists and the Safavid Dynasty [a derogatory nickname for the Assad regime] … Now, “beginning in the era of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi [“Imam Abu Bakr al-Qurashi,” i.e. from the tribe of Quraysh, Muhammad’s tribe], you will see the power of Allah […] and the size of the huge gap between the cowardly secular government […] and the Caliphate of al-Baghdadi […]”

The local government in Al-Raqqah

ISIS was able to establish a governmental center in Al-Raqqah, the so-called “capital of the Islamic Caliphate.” The ISIS leadership in Al-Raqqah is headed by a local emir assisted by foreigners who came from Iraq and other Arab countries, and others. ISIS provides the Al-Raqqah population with most of the services that enable them to maintain the routine of daily life (water, electricity, fuel, education). It controls prices, regulates commercial activity and brutally enforces strict Islamic law (sharia). In addition, it maintains a communications bureau, reminiscent of the media division of a multinational company (Financial Times Service, as quoted in Globes, September 22-23, 2014).

The execution of a boy in the Al-Raqqah city center on June 10, 2013, on the grounds that he expressed contempt for the Prophet Muhammad (youtube.com)

ISIS provides Al-Raqqah with electricity and distributes fuel to its residents. It has also brought life in the city back to normal: American reporters who visited the city (under ISIS control) reported that traffic policemen supervised the intersections, crime in the city was rare, and ISIS tax collectors issued receipts for taxes they collected. In the other hand, ISIS has forced the population to follow strict Islamic law: women are forced to wear the veil; thieves’ hands have been cut off in public; young men and women are forbidden to mingle in public; cigarette smoking has been banned; statues perceived as blasphemous by ISIS have been destroyed. Local residents who speak out against the draconian laws of ISIS are tried before Islamic courts and charged with heresy in Islam, or simply “vanish” (Time.com, December 20, 2013; Nytimes.com, July 26, 2013).

A New York Times correspondent who spent six days in Al-Raqqah said that ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi called on doctors and engineers to come to areas controlled by ISIS, such as Al-Raqqah, to help the organization establish control. He added that signs of international mobilization to aid ISIS were already evident in the city: the armed operatives manning the checkpoints were often Saudis, Egyptians, Tunisians or Libyans; the emir of Al-Raqqah in charge of the electricity supply was Sudanese and one of the hospitals was run by the Jordanian deputy of an Egyptian. He added that after the victories of ISIS in Iraq, the Jordanian director of the hospital had visited Mosul to organize a local hospital. He returned to Al-Raqqah full of enthusiasm, telling a subordinate that the Caliphate of the Islamic State which began in Al-Raqqah, would spread to the entire region (Nytimes.com, July 26, 2014).

The ISIS propaganda machine spreads the message to Syrian and external audiences that daily life in Al-Raqqah and in other places under ISIS control continues as usual (even in the face of the fighting waged by ISIS and the air strikes by the US and its allies). The “hospitality” given to western correspondents in Al-Raqqah are part of ISIS’s effort to convey the message that life is returning to normal. On the other hand, there is a shortage of reliable information about the real situation in areas controlled by ISIS because the local population fears to speak freely to reporters.

Military parade in Al-Raqqah

On June 30, 2014, ISIS held a military parade in Al-Raqqah. It displayed weapons seized in the offensive in northern Iraq, including tanks and Humvees seized from the Iraqi Army. A Scud missile (inscribed “The Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham”), which was seized in the June 2014 offensive in northern Iraq, was also displayed.

In ITIC assessment, the parade was meant as a show of force to the population, the Syrian regime and the other rebel organizations, following the military achievements of ISIS and the declaration of the establishment of the Caliphate (See below). During the parade a number of ISIS operatives spoke to local residents in one of the public squares, calling on them to swear allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Scud missile displayed in Al-Raqqah bearing the inscription: “The Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham” (YouTube, June 30, 2014) Scud missile displayed in Al-Raqqah (Alhadathnews.net)

Tank in one of the squares in Al-Raqqah (YouTube, June 30, 2014)Vehicles bearing ISIS flags in the victory parade in Al-Raqqah (Alarabiya.net)

Left: ISIS operatives who took over the Governor’s Palace in Al-Raqqah (www.vice.com September 23, 2013). Right: Armenian Church in Al-Raqqah, turned into a da’wah office by ISIS (All4syria.info).

ISIS takeover of the Al-Tabqa military airfield

Over the course of several weeks in August 2014 battles were waged between the Syrian Army and ISIS forces near the Al-Tabqa airfield, the last stronghold of the Syrian Army in Al-Raqqah province. Al-Tabqa has great military importance for both sides, in that it provided the Syrian Army with a base for air strikes against key ISIS targets near the “capital city” of Al-Raqqah. For ISIS, taking over the Al-Tabqa airfield would help it establish a firm foothold in the Al-Raqqah province as a whole and reducedthe influence of the Syrian regime.

On August 26, 2014, ISIS announced that it had taken over the airfield, thus completing its takeover of the whole province. Dozens of Syrian soldiers were apparently killed in the fighting and hundreds were taken prisoner. ISIS distributed pictures of Syrian soldiers (including a pilot) who were taken prisoner during the attack. It also distributed pictures of weapons it seized, including at least three MIGs, anti-aircraft missile systems and other weapons systems. ISIS has also reported that its fighters used unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to collect intelligence before taking over the airfield (MEMRI.org, September 13, 2014).

On September 6, 2014, the ISIS media outlet Al-I’tisaam Media Foundation issued a video showing ISIS operatives capturing more than 200 Syrian soldiers trying to escape from the Al-Tabqa airfield after it was taken over. The soldiers were marched to a site where they were shot at close range (Dailymail.co.uk, August 29, 2014; MEMRI.org, department 13, 2014).

The Ayn al-Arab (Kobanî) campaign

Overview

The Kurds, who are Sunni Muslims, are now the largest ethnic minority in Syria, estimated at almost 10% of Syrian population. Most of them live in northern and eastern Syria, mainly in Al-Hasakah, Aleppo and Al-Raqqah provinces. The Kurds took advantage of the political and security void created by the disintegration of the Syrian government to strengthen themselves militarily and establish self-government in their population centers. To protect themselves, they set up their own military militia force called Yekîneyên Parastina Gel (YPG, “People’s Protection Units”), affiliated with the Turkish organization PKK. The YPG forces have established a foothold in Al-Hasakah province and in the northern part of Aleppo province, near the border with Syria.

That brought the Kurds into conflict with ISIS’s establishing its control in eastern and northern Syria, where it displays hostility towards minorities and ethnic groups and strives to impose its strict, radical version of Islamic law on the local population. ISIS particularly wants to take over the Kurdish regions near the border with Turkey to continue its uninterrupted flow of operatives and weapons and to make it more difficult for its enemies and rivals to communicate with their foreign supporters. Another possible motive could be taking over large wheat silos located in the Ayn al-Arab area.

The current ISIS-Kurdish militia conflict arena is Ayn al-Arab (Kobanî) and the surrounding Kurdish region in the Aleppo province near the Syrian Turkish border. At the end of July 2012 the Kurdish YPG militias took control of Ayn al-Arab (Kobanî). The Kurds regard Kobanî as part of Syrian Kurdistan, whereas ISIS strives to impose its control over the entire Kurdish region. Thus in the summer of 2014 ISIS was involved in clashes with Kurdish militias near the Tell Abyad and Ras al-Ayn border crossings adjacent to Ayn al-Arab (See map below).

The Ayn al-Arab area, near the Syrian-Turkish border, the scene of the ongoing battles between ISIS and the Kurdish militias (Google maps)

ISIS’s campaign against n the Ayn al-Arab area began in mid-September 2014. It concentrated a force of an estimated 3,000 fighters (AP.com, November 4, 2014). In the offensive, ISIS forces used tanks and artillery to take over cities, towns and villages in the region surrounding the city and besieged the city of Ayn al-Arab. On October 7, 2014, after about three weeks of fighting, they entered the city, took control of its eastern and southern outskirts and waged street battles with the Kurdish militias. With American air support, the Kurdish militias halted the ISIS advance. At this point, they apparently maintain their control over most of the city. According to a Kurdish operative, ISIS now controls 30% of the area of Kobanî (Alaraby.co.uk, November 12, 2014).

Left: Tank with the organization’s flag in the Ayn al-Arab area (YouTube). Right: ISIS operatives at the entrance to Ayn al-Arab (Syriansnews.com).

American support

The United States supports the Kurdish militias fighting in Ayn al-Arab in two ways: with its coalition allies, it carries out intensive air strikes on ISIS targets in Ayn al-Arab and its environs (diverting effort to Ayn al-Arab from other regions). In addition, 28 crates of supplies for the Kurdish militias have been air-dropped. They contained weapons, ammunition and medical equipment (Fox News, October 21, 2014). At least one fell into the hands of ISIS. At the political level, the US has put pressure on Turkey to allow aid for Ayn al-Arab to arrive from its territory (See below).

Hand grenades dropped from the air for the Kurdish militias and seized by ISIS (YouTube, October 20, 2014)

The Turkish aspect

During the conflict in Ayn al-Arab, Turkish army troops on the Turkish side of the border monitored the fighting and were ready to keep the fighting from infiltrating into their territory. In the first weeks of the fighting Turkey refused to allow Kurdish reinforcements to pass through Turkey on their way to Ayn al-Arab. That was due, first and foremost, to Turkey’s fundamental desire to prevent the Kurds in Syria from gaining strength. Turkey regards the YPG as a terrorist organization and fears that strengthening the separatist aspirations of the Kurds in Syria will strengthen the PKK. Turkey also does not want military involvement in the civil war in Syria and wants the US and its allies to focus on the Assad regime (rather than against ISIS). Turkey apparently also fears it will become a target for ISIS and global jihad terrorist attacks.

In the second half of October 2014, Turkish policy regarding aid to Ayn al-Arab changed, possibly under pressure from the United States. For the first time since the beginning of the Ayn al-Arab campaign, Turkey permitted the Peshmerga forces and Free Syrian Army soldiers to enter its territory and reinforce the YPG militias. On October 28, 2014, reinforcements of 150 Peshmerga soldiers departed from Erbil, capital of Iraq’s Kurdish autonomy. Some traveled by airplane, landed in Turkey and from there made their way to Ayn al-Arab. Some left Erbil by land in a convoy of artillery and anti-tank weapons to Ayn al-Arab.

In addition, the Turks allowed 150 Free Syrian Army reinforcements to travel to Ayn al-Arab via Turkish territory. A Free Syrian Army force crossed the border on October 29, 2014, and joined the Kurdish militias (AFP.com, October 29, 2014).

It was the first time significant reinforcements had reached Kurdish militias since the fighting in Ayn al-Arab began. The effect is still unclear. The reinforcements might make it easier for the YPG to hold back the ISIS forces in the city of Ayn al-Arab and help them force the ISIS forces to withdraw from occupied several neighborhoods and regions.

Results of the battles to date (mid-November 2014)

On movement 10, 2014, the London-based Syrian Human Rights Monitoring Centre reported that since the beginning of the attack on Ayn al-Arab, 1,013 people had been killed. Of them, 609 were ISIS operatives and 363 were combatants in YPG units. According to Kurdish sources and an Al-Jazeera report, two local senior ISIS commanders were killed in Ayn al-Arab: Abu Ali al-Askari (or, according to another version, al-Ansari), who was the commander of ISIS in Ayn al-Arab, and his assistant Abu Muhammad al-Masri (Al-Darar al-Shamiah, November 16, 2014; Al-Jazeera TV, November 17, 2014).

Most Ayn al-Arab’s opinion fled. As a result of the fighting in the city and the surrounding region, an estimated 160,000 Kurds have fled from their homes, most of them to Turkey, which is already coping with a major wave of refugees from Syria. The media reported that a small number of refugees were still in Syria, near the Turkish-Syrian border.

Implications

At this stage, it is difficult to verify the results of the campaign for the city of Ayn al-Arab and its environs, which have great importance for all parties. The possibility that the city and its environs may be occupied by ISIS has the following implications:

- The fall of the entire area is liable to establish ISIS in northern Syria giving it uninterrupted territorial control along the Syrian-Turkish border, where there are three international crossings: Tell Abyad, Ayn Arab, and Jarabulus. That will make it easier for ISIS to secure the vital logistic passage from Turkey, through which operatives and supplies arrive, and will make it harder for its rivals and enemies to maintain contact with their supporters outside.[35]

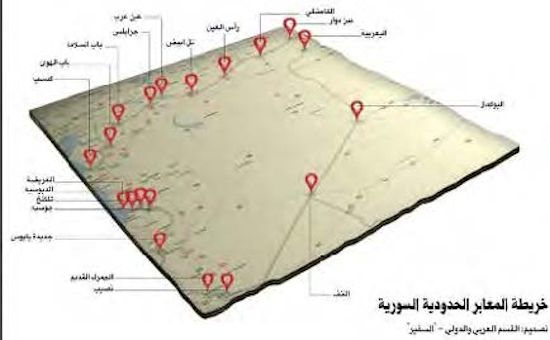

International border crossings between Turkey and Syria (from east to west): Qamishli, Ras al-Ayn, Tell Abyad, Ayn al-Arab, Jarabulus, Bab al-Salama, Bab al-Hawa and Kessab (Assafir.com). The Tell Abyad and Jarabulus border crossings (controlled by ISIS) and the Ayn al-Arab border crossing (which is now being fought over) are marked in red.

- The fall of the area will harm the military and political power of the Kurdish militias in Syria. From a Turkish political perspective, that may expose the Turkish regime to accusations failing to provide support for the Kurdish militias against ISIS. In turn, that may endanger the ceasefire and the current peace process between Turkey and the Kurdish underground (PKK). It may also increase tension between Turkey and the US regarding Turkey’s role in the coalition against ISIS.

- The fall of the area would be the most outstanding achievement of ISIS since President Obama’s decision to undertake a campaign against the organization. It would be interpreted as an American failure, especially since the United States has invested a major effort in air strikes aimed at preventing the fall of the city. On the other hand, a failure by ISIS in the Ayn al-Arab campaign would be a severe blow after its series of successes in Syria and would strengthen its opponents, especially the Kurdish militias in Syria.

ISIS’s efforts to establish itself in the rural areas around Aleppo and the border crossings

The battle to wrest the Ayn al-Arab area from the Kurdish militias is part of ISIS’s effort to establish itself in the rural areas around Aleppo, from the outskirts of the city to the Syrian-Turkish border. In recent months ISIS has exerted military pressure designed to weaken the rebel organizations in the rural areas of Aleppo, including the Al-Nusra Front, Ahrar al-Sham and the Free Syrian Army. ISIS is also trying to win the hearts and minds of local residents by establishing an alternative governmental system that provides essential services (as it has done in other provinces) and financial inducements (promises that the money in its coffers, i.e., revenue derived from the sale of oil products, will be used to provide services to the local population).

Establishing an ISIS administration in the Aleppo province

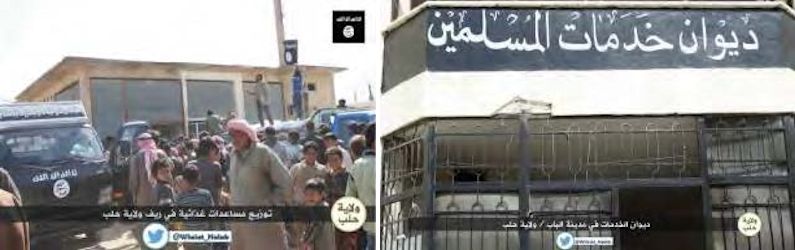

Left: The ISIS Ministry of Da’wah (preaching, political-religious indoctrination) in the city of Maskana, Aleppo province (sef.ps). Right: The ISIS Bureau of Charity (Diwan al-Zakat(36)) in Jarabulus, in Aleppo province (sef.ps).

Left: Distribution of humanitarian aid by ISIS to the rural areas of Aleppo (Sef.ps). Right: The Bureau of Muslim (social) Services in the city of Al-Bab, in Aleppo province (Sef.ps).

Enlisting new operatives into the ranks of ISIS

As in Iraq, in the summer of 2014 ISIS made efforts in Syria to enlist new operatives from the local population. Its military achievements, the establishment of the Caliphate State and its increased financial resources motivated residents to join its ranks, swelling the number of recruits. Most of the jihadi training camps belong to ISIS.

ISIS enlistment is carried out in the various provinces by local recruitment offices. New recruits undergo several months of training before they join the ranks of the organization. There are recruitment offices and training camps in the various provinces in eastern and northern Syria controlled by ISIS, among them in Aleppo, Al-Raqqah, Dir al-Zor and Al-Hasakah. ISIS’s information offices occasionally publish photos when the training courses end. ISIS has 25 training camps, 14 in Syria and 11 in Iraq. Most of those in Syria are located in the provinces of Aleppo, Al-Raqqa and Dir al-Zor. In addition, there are several training camps in the provinces of Al-Hasakah, Latakia and Damascus. The camps have been the targets of US attacks since the beginning of August 2014 (Longwarjournal.org, November 22, 2014).

Photo distributed by ISIS’s information office in the Aleppo province showing a new group of mujahedin (jihad fighters) who completed their training (Longwarjournal.org, July 26, 2014)

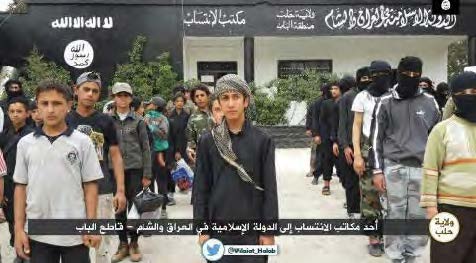

Recruitment office enlist new operatives in the ranks of ISIS, including teenage boys from the Aleppo province in the Al-Bab region (Alfetn.com)

Recruits at the entrance of the ISIS recruitment office in the city of Al-Bab, northeast of Aleppo. The recruits in the photo are mainly boys and teenagers (Islahjo.com).

Ceremony marking the end of a training course for ISIS operatives at the al-Zarqawi camp in Al-Raqqah (Alarabiya.net). The photo was issued in March 2014.

Omar the Chechen, a prominent figure in the ranks of ISIS in northern and eastern Syria

In establishing its control in eastern Syria, ISIS availed itself of the military skills of a Chechen jihadist from Georgia, whose nickname is Omar al-Shishani, i.e., Omar the Chechen. Until the end of 2013 he headed an elite military framework called the Army of Emigrants, which was associated with the Al-Nusra Front. In early 2014, he defected to the ranks of ISIS and was appointed as its commander of the northern region of Syria. Initially, Omar the Chechen’s activity was concentrated in the Aleppo region, the source of his power. However, in the first half of 2014 he expanded his activity to the east as well, all the way to Dir al-Zor.

During the course of his activity in eastern Syria, serious disputes arose between ISIS and other Islamic organizations due to ISIS’s brutal treatment of the population and its attempt to impose radical Islam. According to an unverified report, he currently serves as Chief of Staff of the Islamic State, which refers to him as its military commander (See Section Five).

Establishing enforcement networks in northern and eastern Syria

Islamic law enforcement networks

ISIS brutally imposes its Salafist-jihadi Islamic ideology on the population in the areas under its control Syria and Iraq. Its two main enforcement networks are the Islamic Police, which carries out routine policing duties, and the Morality Police (hisbah), which deals with the enforcement of religious commandments and is separate from the regular police.

ISIS has an extensive network of prisons and detention facilities in the areas under its control. Article 38 of a report published by a UN commission of inquiry examining the lives of the population under ISIS’s reign of terror described the system of prisons and detention camps as follows (Ohchr.org, November 14, 2014):

“ISIS has set up detention centers in former government prisons, military bases, hospitals, schools and in private houses. Former detainees described being beaten, whipped, electrocuted and suspended by their arms from walls or the ceiling. Witnesses to public executions remarked that the victims often bore signs of prior beatings. Detainees are held in dirty and overcrowded cells. Many spent long periods of time in handcuffs. Detainees interviewed stated that neither they nor their cellmates received medical treatment. One detainee recalled a FSA fighter being left in his cell beaten, with his hands cuffed behind his back and an open fracture on his leg.”

Left: Confiscation of cigarettes in the Idlib province (Theshamnews.wordpress.com) Right: ISIS’s Islamic Police vehicle in the Idlib province (Enqazsyria.com).

Left: ISIS’s Islamic Police station in the town of Manbij, in the rural areas of the Aleppo province (breakingnews.sy). Right: ISIS’s Islamic Police station in the city of Maskana, Aleppo province (Sef.ps).

The Morality Police (Hisba)

Hisba is an Islamic endorsed by the Qur’anic decree “Enjoining good and forbidding wrong,” which can be translated as “supervising the existence of justice.” The functionary in the historic Islamic State responsible for enforcing the decree is called the muhtasib, who played a supervisory role in the markets in the Middle Ages (at least since the days of the Abbasid Dynasty). He supervised weights and measurements in markets, the rules of construction, honesty in commercial negotiations and public and religious morality (including the rules of modesty).

In Islamic history, the muhtasib was considered a law enforcement officer, a type of police officer, and in cases where he deemed it necessary he arrested criminals and brought them before an Islamic judge (qadi). The muhtasib could also serve as a judge and impose punishment (a kind of on-site judgment) and arbitrate between adversaries. The many hisba books published over the centuries describe his role and conduct and are an important source of knowledge of the world of Islam in the Middle Ages. Today’s “modesty patrols” in Saudi Arabia and Iran operate according to a format similar to that of the muhtasib and under the same Qur’anic decree.

ISIS claims to have ten Morality Police headquarters in Aleppo province and additional headquarters in Al-Raqqah province (ISW, ISIS Governance in Syria, July 2014). Unlike regular policing, which deals with criminal matters, ISIS’s Morality Police enforces religious commandments. For example, they remind local residents to take part in Friday prayers, prohibiting them from conducting business during prayers; they fight the sale and use of drugs and oversee the destruction of statues and sites of those who are considered “idol worshippers.”

Posters distributed by ISIS in Al-Raqqah province informed the population that the electricity in Al-Raqqah would be disconnected during the religious Muslim month of Ramadan, it is a month of worship rather than entertainment. The posters stated that in the time of the Prophet Muhammad there was no electricity. The organization also prevented local citizens from operating generators (except in essential facilities) to keep them from watching the World Cup soccer games which, in its opinion, was liable to distract the residents from the work of God (Assifir.com, June 16, 2014).

Morality Police headquarters in the city of Manbij in Aleppo province (Ynewsiq.com). The inscription on the car reads “Enjoining good and forbidding wrong;” it is the Qur’anic decree under which the Morality Police operates.

Women also serve in the Morality Police, enforcing the Islamic code of conduct, as interpreted by ISIS, on women. They supervise women’s modest dress code and enforce the prohibition on women’s walking or working in the company of men without a male escort (the wife’s husband or patron) (Syrianews.com). The Syrian Institute for Human Rights reported that on November 12, 2014, “women supervisors” of ISIS were seen patrolling the open markets in the city of Al-Mayadeen, on the outskirts of Dir al-Zor. The women, who were carrying guns, arrested a female resident because she was not wearing proper attire (“sharia attire”).

Women in ISIS’s Al-Khansaa Battalion in Al-Raqqah, who are members of the Morality Police (named after the poet Al-Khansaa, who lived in the time of Muhammad, lost four sons in the Battle of Qadisiyyah and became a symbol of sacrifice and martyrdom) (Onlinenews.cc)

Syrian girl named Fatoum Al-Jassem, just before she was stoned by ISIS operatives in Syria. The photo was posted to Syrian opposition websites. How reliable it is or where it was taken is not known (Hasa.com). ISIS carried out executions of women accused of adultery in the cities of Al-Tabqa and Al-Raqqah in July 2014.

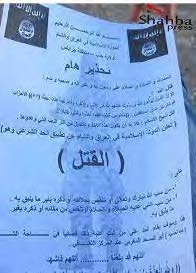

ISIS document, issued in Syria, warning the population that those who curse the Prophet Muhammad will be sentenced to death in accordance with the laws of sharia (All4syria.info).

Show trial in which two apostates (murtaddin, i.e., those who abandoned or rejected Islam were executed in the city of Al-Bab in Aleppo province (Sef.ps)

Execution of a woman charged with prostitution

On October 21, 2014, Al-Arabiya TV broadcast an ISIS propaganda film showing a woman accused of prostitution being led by her father to be stoned. An ISIS operative asked the father to forgive his daughter after she expressed regret, but he refused. The ISIS operative in the film appleased Muslims around the globe to protect their wives and act morally.

Left: The father binds his daughter before she is stoned. Right: ISIS operative (right) asks the father (left) to forgive his daughter for her actions. The father answers that he will not forgive her (the daughter has her back to the camera). The ISIS flag appears in the background on top.

In the London-based Al-Sharq al-Awsat Arabic-language daily newspaper, columnist Abdul Rahman Al-Rashed wrote about the execution of the woman and its exploitation for propaganda purposes by ISIS, as follows (October 24, 2014):

“Why does ISIS insist on spreading a video showing its fighters stoning a woman to death with the participation of her father? This video will remain one of the vilest and most offensive to Muslims. At the same time, it serves as evidence not only of the organization’s barbarity, since that has already been established, but also of its ability to remain on the front page, exploiting it for its needs and thereby gaining an important advantage. The organization’s abhorrent actions achieved its goals via the media.

“ISIS’s objective is to show people the most extreme and cruel photos of beheadings, massacres of defenseless civilians, persecution and stoning of women. Even Al-Qaeda, which made use of photographed violence, did not persist the way ISIS’s fighters do.

“Those acts of barbarism and violence aren’t marketed to people as proof of ISIS’s cruelty, but at the same time the organization is working to convince people that it acts correctly according to Islam and constitutes an alternative government; and that it is capable of recruiting many through provocations, changes and the dissemination of its perception of Islam. The offensive video shows how extremists convince an ignorant father that if he stones his daughter she will quickly reach paradise, cleansed of her sins, and so they manage to persuade the girl to agree to be stoned, because by doing so she will atone for her crimes.

This video was posted by ISIS operatives, but they were careful not to mention what happened in the city of Al-Raqqah in Syria, where residents gathered in the square near the municipal field to stone a girl but refused to participate, and ISIS fighters stoned her. The organization has not distributed that video because it knew that the residents were opposed to it and the condemnations they would voice would not constitute suitable propaganda material”

Attacks and harassment of Christians and other religious minorities

ISIS harasses Christians and other religious minorities in the areas under its control. A UN international commission of inquiry which examined ISIS’s rule of terror of Syria published a report entitled, “Rule of Terror: Living under ISIS in Syria.”[37] The following three sections of the report pertain to the harassment of Christians (Ohchr.org, November 14, 2014):

“Where ISIS has occupied areas with diverse ethnic and religious communities, minorities have been forced either to assimilate or flee. The armed group has undertaken a policy of imposing discriminatory sanctions such as taxes or forced conversion — on the basis of ethnic or religious identity — destroying religious sites and systematically expelling minority communities. Evidence shows a manifest pattern of violent acts directed against certain groups with the intent to curtail and control their presence within ISIS areas.

Between September and October 2013, ISIS fighters attacked three Christian churches in Ar-Raqqah governorate, destroying the Greek Catholic church; occupying Al-Shuhada Armenian Orthodox church in Raqqah city and burning an American church in Tel Abyad. As ISIS spread throughout eastern Syria, Christians and their places of worship continued to be attacked. In September 2014, ISIS fighters destroyed an Armenian church in Dayr Az-Zawr.

On 23 February 2014, ISIS published a statement addressing Christians that had fled Ar-Raqqah establishing conversion to Islam and the payment of a jizya tax as conditions for their return. The forced conversion of several Assyrian Christians has been documented.”

The ISIS educational system

Overview

In the wake of the civil war in Syria, the state education system in many areas collapsed and has ceased to function. ISIS has taken over the Syrian educational infrastructure in the areas under its control, setting up alternative educational systems.[38] ISIS has invested considerable resources in its educational systems. ISIS considers it important to educate the next generation in Syria according to its own ideology, since Syria is a country with a long tradition of secular education. It is part of ISIS’s strategy to foster a new generation of adolescents in Syria who support ISIS’s radical Islamic ideology. Control of education also strengthens ISIS’s position within the local population as the organization providing it with essential services.

In the areas under its control, ISIS has established a formal education system at state schools that do not operate regularly. At the same time it is also setting new educational institutions of its own. ISIS maintains an informal education system consisting mainly of military training camps for children and teenagers, where the children undergo Islamic indoctrination according to ISIS ideology and hold various Islam-oriented events (such as Qur’an reading contests).

The formal education system

Left: Schoolbag of a girl in Aleppo with the ISIS insignia and name (MEMRI.org, September 9, 2013). Right: Syrian children attend an ISIS school, with the organization’s flag visible in the background (the organization’s Aleppo)

Left: Schoolchildren waving an ISIS flag (Twitter.com, April 5, 2014) Right: Schoolchildren in Aleppo with an ISIS flag (MEMRI, September 9, 2013).

ISIS has imposed gender separation at the schools it operates. ISIS also requires girls from the age of kindergarten to wear Islamic dress as a condition for attending school. ISIS offers services designed to encourage children to attend school, for example, transportation (The Dawn of the Islamic State of Iraq and ash-Sham, Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, Current Trends in Islamic Ideology, Vol. 16).

The first evidence of the ISIS educational system appeared in a video issued by Al-Furqan Media, one of ISIS’s designated media bodies (September 6, 2013). The video shows a sheikh, who identified himself as Abu Omar the Syrian, teaching a Qur’an class in Al-Raqqah. Approximately 50 children were in attendance, all wearing ISIS headbands and reading the Quran. The writing on the blackboard reads: the reasons for prayer, how to pray, the importance of prayer. Photos distributed by ISIS in September 2013 showed a school in Aleppo province run by ISIS. The photos show schoolbags for students bearing the ISIS insignia (Charles C. Caris, Samuel Reynolds, Middle East Security Report, ISIS Governance in Syria, July 2014).

In April 2014, ISIS announced the establishment of a new school in the city of Al-Raqqah intended for high achievers. Earlier, in March 2014, ISIS searched for teachers of various subjects. The photos of the interiors and exteriors of the buildings suggest that many of ISIS’s schools are existing Syrian state schools now being run by ISIS. The organization also provides students with textbooks. Classes are large, some with as many as 60 students (Charles C. Caris, Samuel Reynolds, Middle East Security Report, ISIS Governance in Syria, July 2014).

ISIS’s “educational” effort targeted at elementary schools, at least during 2014. Due to the narrowness of ISIS’s educational system, it has nothing to offer in the field of university-level education. In Al-Raqqah several sharia institutes have been used for Islamic preaching meetings (da’wah) for college students. ISIS also provides religious-educational settings in mosques in Al-Raqqah and other cities (The Dawn of the Islamic State of Iraq and ash-Sham, Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, Current Trends in Islamic Ideology, Vol. 16).

Religious education: The sharia institute of the sources of religion for men in the town of Maskana in the Aleppo province (Sef.ps)

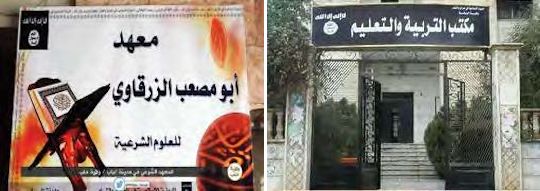

Left: The entrance to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi Institute for the Study of Islamic Law (sharia) in the city of Al-Bab in the Aleppo province (sef.ps). Right: The ISIS Ministry of Education and Culture building in Al-Raqqah (The organization’s Twitter account).

Curriculum

ISIS’s curriculum focuses on the study of Islam and the Quran at the expense of secular subjects and the acquisition of technological skills. The ISIS Ministry of Education has issued a series of orders forbidding the teaching of subjects such as music, art, history, the social sciences, philosophy, psychology and Christianity.

According to instructions from the Ministry of Education, the term “the Syrian Arab Republic” in textbooks is to be erased and replaced with “the State of Islam.” Schools have also been ordered to remove any picture defined as inappropriate from the standpoint of sharia law and to stop playing the Syrian national anthem. Students have been forbidden to cultivate Syrian nationalism because the state of every Muslim is any place where sharia law rules. Teaching Darwinism is also forbidden, since Allah created everything. In classes where the laws of chemistry and physics are taught, it is emphasized that they come from Allah. Teachers are required to undergo special training on sharia to be able to continue teaching (ibtimes.co.uk, September 1, 2014).

Religious training of children by the Islamic State in the Al-Raqqah province (Twitter, May 10, 2014).

ISIS first grade textbook entitled Al-Tawhid (The Oneness of Allah) (from the organization’s Twitter account).

ISIS operative lecturing to students about the importance of knowledge of Islam (From the ISIS Twitter account, March 20, 2014)

Informal educational settings

In addition to its formal education system, ISIS operates informal “educational” settings. They are mainly training camps for children and teenagers where they receive military training and radical Islamic indoctrination. The camps are help ISIS train its next generation of fighters in Syria. To that end, a framework for children and teenagers called the Al-Zarqawi Lion Cubs has been established in areas controlled by ISIS in Syria. It is a continuation of the Birds of Paradise unit from Iraq, which is for the recruitment of children under the age of 15. The unit is designed to train children for military missions such as conveying explosives, collecting intelligence and carrying out suicide bombings.

One of the videos documenting the activities at a training camp for children showed several dozen children in military uniforms carrying Kalashnikov assault rifles and undergoing military training ((MEMRI.org, February 7, 2014). Another video of the Al-Zarqawi Lion Cubs was posted to YouTube on May 25, 2013, and showed a youth camp in Abu Kamal in eastern Syria. The video shows masked children receiving arms and ammunition from the camp instructor, marching with a black jihadi flag, receiving religious indoctrination and undergoing weapons training ((MEMRI.org, February 7, 2014).

Left: Children at an Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi Lion Cubs camp during military training (ISIS’s Twitter page, March 22, 2014) Right: ISIS training camp for children in the Damascus area (YouTube, January 2, 2014).

According to a report published by the UN Human Rights Council on August 13, 2014 (A/HRC/27/60), the Islamic State “systematically provides weapons training for children.” The organization has set up training camps throughout the country, especially in Aleppo and Al-Raqqah provinces, for recruiting children and training them for combat. According to the report, that constitutes a war crime and a crime against humanity which has to be referred to the International Criminal Court in The Hague. The report also mentions a training camp in Al-Bab in Aleppo province, which ISIS took over in the fall of 2013. According to the report, children aged 14-15 were recruited into the camp and received financial compensation for their services. The training at the camp included military training and religious education (Ohchr.org, August 13, 2014).

Photo uploaded to social networks showing children in Al-Raqqah gathering around the body of a civilian who was executed (Twitter, October 1, 2014)

The ISIS judicial system

The establishment of an Islamic judicial system in all the areas is controls is of great importance for ISIS. Adoption of Islamic law as the sole source of authority is an important element in ISIS’s vision of the Caliphate. The legal system imposed by ISIS on the population includes severe penalties for whoever violates Islamic law, as perceived by ISIS.

When ISIS expanded its influence in northern Syria in the summer of 2013, it set up sharia courts in several cities. One of the first courts documented was in Jarabulus, in the northern part of Aleppo province, in early July 2013. In November 2013, ISIS extended its judicial system to Idlib province. On June 30, 2014, the ISIS information office in Aleppo province reported on its Twitter account that five sharia courts operated in the province. In the spring of 2014, courts were also set up in Al-Raqqah and Aleppo provinces where residents’ complaints against ISIS operatives or against local emirs were investigated (Charles C. Caris, Samuel Reynolds, Middle East Security Report, ISIS Governance in Syria, July 2014).

In November 2013, an ISIS judge was interviewed in the Idlib province. The judge explained how ISIS filled the void created in the region after the collapse of the Syrian regime’s legal system. He said that when ISIS arrived crime was a great problem in the area, but after the establishment of the ISIS courts there was a significant drop in crime. In an interview with civilians outside the courthouse, one of them said that he made a special trip from Aleppo province in order to be tried (Charles C. Caris, Samuel Reynolds, Middle East Security Report, ISIS Governance in Syria, July 2014).

In summary: ISIS has set up a judicial system in the areas under its control. In ITIC assessment so far the ISIS legal system has been received with resignation and perhaps even favorably by the local population, even though it does not share ISIS’s Salafist-jihadi Islamic ideology. Apparently the local residents perceive the existence of the legal system as beneficial. That is because it fills the governmental void created after the collapse of the Syrian regime and marks the return of law and order, and because the sharia are currently perceived as less corrupt than the Assad regime’s old secular courts.

![]()

[1] Links to all other nine sections:

You can read the overview — “ISIS: Portrait of a Jihadi Terrorist Organization” — here.

You can read section 1 — “The historical roots and stages in the development of ISIS” — here.

You can read section 2 — “ISIS’s ideology and vision, and their implementation” — here.

You can read section 3 — “ISIS’s military achievements in Iraq in the summer of 2014 and the establishment of its governmental systems” — here.

You can read section 5 — “ISIS’s capabilities: the number of its operatives, control system, military strength, leadership, allies and financial capabilities” — here.

You can read section 6 — “Exporting terrorism and subversion to the West and the Arab world” — here.

You can read section 7 — “ISIS’s propaganda machine” — here.

You can read section 8 — “The American campaign against ISIS” — here.

You can read section 9 — “ISIS response to the American campaign (update to mid-November 2014)” — here.

![]()

Notes:

[35] It has been reported that in early November 2014, the rival jihadi organization, the Al-Nusra Front, made preparations to advance towards the Bab al-Hawa crossing in the west (the Idlib province) to take control of it. The crossing is controlled by the Free Syrian Army (Al-Arabiya, November 3, 2014). The crossings between Syria and Turkey will apparently continue as arenas of struggles for power and control between the various opposing forces.

[36] Zakat — Obligatory charity, one of the five pillars of Islam.

[37] Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syria Arab Republic.

[38] According to a March 2014 UNICEF report, about 2.8 million (more than half) of all Syrian school-age children cannot receive regular education because of the civil war. Most of them (around 2.3 million) are located within Syria. Most of the classrooms were bombed or turned into shelters or military posts. About 40% of all school-age children in Syria do not attend school. To this figure can be added more than 300,000 Syrian children in Lebanon, about 93,000 in Jordan, 78,000 in Turkey, 26,000 in Iraq and 4,000 in Egypt. UNICEF estimates that approximately 2 million children are in need of psychological support or counseling (Huffintonpost.com, March 11, 2014).

RSS

RSS

Latest Comments

Hello Mike, Thank you for your positive feedback to the article. I felt there wasn’t too much critical analysis of ...

Thanks for this considered and well constructed article. A follow up article on the manner in which the editorial contro...

THE CLUELESSNESS OF CLAIMING THAT OBAMA'S MIDDLE EAST POLICIES WERE A FAILURE CANNOT BE FURTHER FROM THE TRUTH, WHAT THE...

As long as Obama is the president of the usa do not trust the us government......

Thank you for an good read....