![]()

Mon, March 26, 2012 | By Halil M. Karaveli

This article was first published in the Turkey Analyst, vol. 5 no. 6 (www.turkeyanalyst.org), a biweekly publication of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center. © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center, 2012.

Is there a third way for Turkey, one that would offer an escape from the statist and nationalist authoritarianism to which both Kemalism and Islamism condemns the country? While the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) has increasingly come to embrace an illiberal approach, the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) is attempting to move in the opposite direction. However, the assumption that there is still a significant constituency for liberal change to tap into, as was the case a decade ago, when the AKP first came to power and when EU membership beckoned, is a dubious one. History teaches that it is unlikely that Turkey, left to its own devices, will emancipate from illiberalism.

Background

Turkey’s old habits of state authoritarianism persist under the rule of the AKP; the freedom of expression is severely circumscribed — nearly one hundred journalists are presently held in prison — political opposition, notably of the Kurds, is emasculated with mass arrests, and there are no indications that a new, liberal constitution is forthcoming.

The idea that the purpose of the state is to preserve freedom and protect society and individuals has few adherents in Turkey outside the small liberal intelligentsia in Istanbul. The left and the right alike have been unable or unwilling to disengage from a shared tradition that sanctifies the state and the nation at the expense of the autonomy of society and of individual freedom.

There are historical reasons why the fundamental assumption of Western, liberal political thought that state power is legitimate only as far as it safeguards liberties has not sunk roots in Turkey. Turkish — as generally Islamic — political tradition has been haunted by a primordial fear of anarchy; it remains axiomatic that freedom would impair the state, putting its very existence at risk. Turkish constitutional scholar Mustafa Erdoğan has remarked that “the cultural code of our people dictates that the state, authority, will have to be obeyed regardless of whether it is tyrannical and evil.” It is particularly noteworthy that Fethullah Gülen, the influential Islamic brotherhood leader, has stated that “even the worst kind of state is better than chaos”, and that obedience to state authority figures preeminently in his teachings. Indeed, the Gülenists, who make up a significant part of the new state elites, revere the state and the Turkish nation just as much as the Kemalists, the former rulers of Turkey.

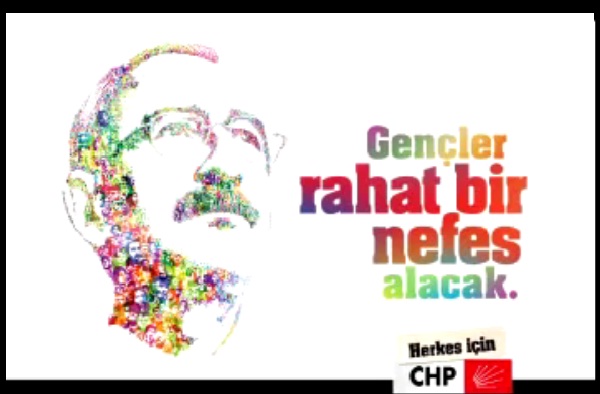

The question is if there is a third way for Turkey, one that would offer an escape from having to choose between different versions of statist and nationalist authoritarianism. Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the CHP leader, is attempting to explore such an alternative. Kılıçdaroğlu is laboring to reinvent the party of Kemalism; he is trying, albeit hesitantly and cautiously, to renew the party by disengaging from its traditional statism and nationalism. A recent party conference, in February, confirmed that Kılıçdaroğlu, who unexpectedly was handed the leadership two years ago, has by now succeeded in establishing his authority over the party organization. The conference adopted new statutes for the CHP that mirror Kılıçdaroğlu’s ideological ambitions.

According to the old version of the party statutes, the main aim of the CHP was to “protect and enhance the security and integrity of the country”. Although that still remains one of the aims of the party, it is no longer mentioned first; instead, the main priority of the CHP is stated to be to “create a just system that rests on a foundation of human rights, the rule of law, a secular, modern, participatory and pluralistic democracy.” Kılıçdaroğlu emphasizes that “we have moved human rights, democracy and freedoms to the front”; in a sense, the CHP has been endowed with a “constitution” that denies “state security” its erstwhile preeminence over freedom, prefiguring the change that Kılıçdaroğlu is envisioning for the country.

Appearing on a news show on television on March 8, the CHP leader vowed to solve the Kurdish issue and stated that he is prepared to take any risk to that end, including the risk of ending his own political life. Kılıçdaroğlu certainly took a significant risk when he stated that it is inappropriate to include references to ethnicity in the constitution, and suggested that it would be more appropriate to introduce the notion of “citizenship of the republic of Turkey” as a supra-identity of the country’s inhabitants. That amounts to a head-on challenge of the bedrock beliefs of Turkish nationalism, be it secular or Islamic.

Implications

The Turkish constitution recognizes no other identity than Turkishness, and it enshrines it as the sole societal norm; that in turn has been defended with the claim — which is not entirely untrue — that Turkishness is not an ethnic identity, but an identity which everyone, regardless of ethnic origins, can embrace. However, the implication of Kılıçdaroğlu’s remarks is that Turkishness is, precisely, an ethnic identity among others and that it should not enjoy any privileged status at the expense of the other identities of Turkey.

Kılıçdaroğlu, whose Alevi and Kurdish origins sensitizes him to the perspectives and experiences of the “others” of Turkey, was immediately rebutted by his predecessor Deniz Baykal, who saw fit to impress the absolute necessity of preserving Turkishness as the sole basis of the state; Baykal warned that if ethnic and sectarian differences are allowed to supersede national unity, societal cohesion would be threatened, and he referred to Syria as a warning example.

There can be no doubt that the remarks of the former CHP leader resonate not only among the electoral base of the CHP, but among the Turkish public in general. Kılıçdaroğlu’s endeavor to reinvent the CHP, charging it with the new task of promoting freedom, rather than being the agent of state security, rests on the assumption that there is a significant constituency for liberal change into which the CHP would successfully tap. However, it is not only far from certain that Kılıçdaroğlu will ultimately succeed in carrying his own party with him, it is also the assumption that liberal reformism stands to be electorally rewarded that is dubious.

That assumption is to a certain extent a by-product of the AKP’s successes, but it may nonetheless be misleading: the AKP owed its ascension to its ability to appeal to a wide electorate, by presenting itself as a force that challenged an ossified status quo, holding out the promise of EU-inspired reforms. That is something that Kılıçdaroğlu hopes to emulate, as he assures that the CHP no longer is the party of status quo, but that it stands for the universal principles of social democracy. But that electoral calculus may suffer from a time-lag.

The Turkey of 2012 is not the Turkey of 2002, not even of 2007. While the AKP’s first two victories did speak of a societal yearning for democratic change — in 2002, the AKP was the party of EU reforms, and in 2007 it was rewarded for its stance against military tutelage — its most recent and greatest landslide, in the general election in 2011, was instead secured by more time-honored tactics, notably by playing the nationalist card. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan campaigned as a fierce Turkish nationalist, claiming that he would have hung the imprisoned PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan if he had been in power when he was handed over to Turkey.

Erdoğan’s tactic is clearly to tap into the illiberal current that runs through much of Turkish society, and more precisely into the reservoir of the right-wing Nationalist Action Party (MHP). The most recent manifestation of that tactic was the public rally organized by the AKP in Istanbul’s main Taksim square on February 26 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the massacre that was committed by Armenian forces in Khojaly in Azerbaijan. The main speaker at the rally was the interior minister İdris Naim Şahin. The participants displayed placards that threatened Armenians — and Turks who challenge the nationalist discourse.

In an allusion to the public manifestation in 2007 at the funeral of the slain Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink, when one hundred thousand Turks took to the streets in Istanbul to demonstrate their solidarity with the Armenians, carrying placards that announced “We are all Armenians”, demonstrators at the Khojaly rally carried placards announcing “You are all Armenians, you are all bastards”, the latter a reference to the novel “The bastard of Istanbul” by Turkish author Elif Şafak who created a furor a few years ago by broaching the issue of what had happened to the Armenians in 1915, and who was subsequently put on trial for having insulted Turkishness.

Interior minister Şahin refused to comment on the placards, let alone condemn them, while Prime Minister Erdoğan, who also declined to issue any condemnation, declared that such “marginal expressions” was not going to deflect his government from giving voice to the feelings of sorrow of the nation.

Conclusions

Turkish ultra-nationalism is in fact far from being marginal; it was certainly not marginal at the time of Hrant Dink’s murder, but in 2007 those liberal-minded Turks who expressed their solidarity with the Armenians could think of the AKP as an ally in the struggle against an authoritarian, nationalist state apparatus that was suspected of having been involved in the murder, and they were encouraged by the prospect of EU membership. That the AKP today is the organizer of an ultra-nationalist rally is suggestive of the persistence of old habits, and of the resistance of entrenched Turkish political tradition to liberal change. And with the disappearance of the EU vision, Turkish liberalism has lost all impetus.

History teaches that the confluence of external pressures and/or encouragement and internal power considerations is required to bring about liberal reform in the Turkish realm. That was the case with the “Tanzimat” reform period between 1839 and 1876, with the U.S.-inspired introduction of a multiparty system in 1946-1950 and with the EU reform period in 2002-2005. It is unlikely that Turkey, left to its own devices, will emancipate from illiberalism.

Halil M. Karaveli is Senior Fellow and Managing Editor of theTurkey Analyst at the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center.

RSS

RSS

Latest Comments

Hello Mike, Thank you for your positive feedback to the article. I felt there wasn’t too much critical analysis of ...

Thanks for this considered and well constructed article. A follow up article on the manner in which the editorial contro...

THE CLUELESSNESS OF CLAIMING THAT OBAMA'S MIDDLE EAST POLICIES WERE A FAILURE CANNOT BE FURTHER FROM THE TRUTH, WHAT THE...

As long as Obama is the president of the usa do not trust the us government......

Thank you for an good read....