![]()

February 2013 | MEForum | by Raymond Stock

Originally published in Foreign Policy Research Institute.

“You know, when it comes to Egypt, I think, had it not been for the leadership we showed, you might have seen a different outcome there.” — President Barack Obama, “60 Minutes,” January 27, 2013

With President Mohamed Mursi’s proclamation of a “new republic” on December 26, after the passage of a Constitution that turns Egypt into an Islamist-ruled, pseudo-democratic state, the “January 25th Revolution” came to a predictably disastrous (if still unstable) terminus. As momentous for world history as the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran (should it hold), it represents the formal — if not the final — victory for the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) in its 84-year struggle for power in the land of its birth. Indeed, 2012 will likely be remembered as the year that Islamists made the greatest gains in their quest for a new caliphate in the region. And without a drastic change of course by Washington, 2013 might surpass it by far in progress toward the same, seemingly inexorable end.

Egypt, the largest Arab state, the second largest recipient of U.S. military aid, and our second most important ally in the Middle East, is now in the hands of a hostile regime — an elected one at that — which we continue to treat as a friendly one. Even if the sudden outburst of uncontrolled violence along the Suez Canal since January 26 — coupled with escalating political and economic tumult in Cairo and elsewhere — leads to a new military coup, it would likely be managed by the MB from behind the scenes. The irony and the implications are equally devastating. This new reality threatens not only traditional U.S. foreign policy goals of stability in the oil-rich Middle East and security for Israel, but also America’s declared support for democracy in the Arab world. Moreover, the fruits of Islamist “democracy,” should it survive, are catastrophic to the people of Egypt, the region and beyond.

How did all this happen? And what role did the U.S. play?

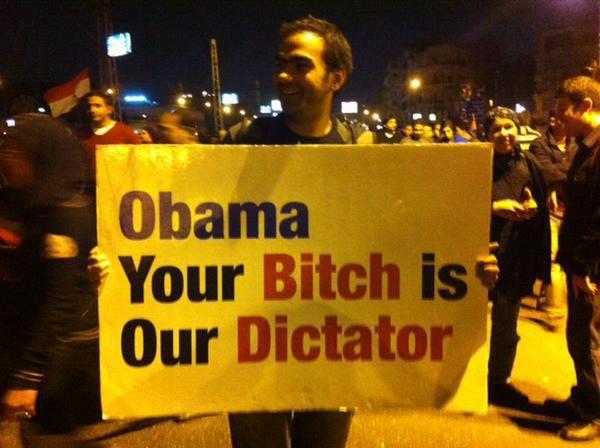

America: a Beast of Burden?

In an earlier E-Note[1] I wrote that Egyptians compare a farsighted leader to the camel — a creature that gazes serenely at the horizon as it plods patiently towards its goal. Conversely, they think of a poor leader like the donkey — a timid but obstinate animal that stares at the ground as it blunders along. Though popular jokes often cast President Hosni Mubarak as a donkey, when it came to seeing what and who would follow him if Obama hastily pushed him from power, he was actually like the camel. In a February 3, 2011 televised interview with Christiane Amanpour, Mubarak said that he had personally warned Obama there would be chaos and Muslim Brotherhood rule if he was forced to step down at that time. Soon he proposed instead turning over some of his powers to a vice-president until the presidential elections, then set for that September, in which neither he nor his son Gamal, who had seemed set to succeed him, would take part. (As his V.P., Mubarak named General Omar Suleiman, the head of Military Intelligence, who had extensive experience both repressing and negotiating with the MB, and was seen by the West as a safe pair of hands.) Though a great many demonstrators seemed to accept this compromise, many others — and the White House would not. On the evening of February 10, Obama issued a statement that the Egyptian people thought the transition to democracy was not happening fast enough. By the next evening in Cairo, Mubarak had stepped down.

Mubarak’s prediction turned out to be right. When he resigned, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), which had always been subservient to the president, took over state power, which it promised to relinquish after elections for parliament and president, and the approval of a new Constitution. Throughout the demonstrations against Mubarak, the SCAF had been negotiating with a coalition of opposition groups, represented by the MB, and with the U.S. as well. For the next year and a half the SCAF cooperated closely with the MB in running the country, while the secular liberals and some Salafi groups waged an almost uninterrupted campaign of often-violent protests (that were met with crushing force) to demand a speedier turnover of power to “civilian rule.” They should have realized that could only mean a handover to the MB and its own Salafi allies — even those who did understand this innocently thought the Islamists would keep faith with their promises to honor democracy in the end. Amid constant bloody demonstrations, incessant, widespread strikes, intensified persecution of Christians and skyrocketing crime, the Brotherhood rode confidently to state power in large part on the back of the Obama administration. The load was shared by the willing Egyptian armed forces that were filled with Islamist sympathizers (leavened with Mubarak loyalists at the top), not to mention the demonstrators in Tahrir Square and around the country. But the American role was crucial.

Few observers knew the MB itself had actually mobilized the protesters in much larger numbers than had the secular liberals on Facebook and Twitter who got the credit for starting the revolution. Indeed, by the second day of demonstrations (on Friday, January 28, 2011), the MB’s ability to bring protesters onto the streets dwarfed that of their secular liberal allies, key figures among whom had their own, little-known links to the Brotherhood that the media, government and experts missed entirely. Chief among these was Wael Ghonim, the charismatic young, Dubai-based Google executive, who (as documented in my earlier E-Note) few people knew then knew had been a member of the MB in his late teens. Another— whom a leading MB figure, Essam El-Erian, has described as owing his political loyalty to the Brotherhood—was Alexandrian activist Abdel-Rahman Mansour. Along with Ghonim, Mansour ran a Facebook page, “Kullana Khaled Said” (“We are All Khaled Said”) that played a key role in launching the January 25 protests.

America’s role as the MB’s primary beast of burden didn’t begin even with the January 25th Revolution. Or rather, the revolution did not start on that date. Arguably, it really began on June 4, 2009. On that day, Obama gave his famous “speech to the Islamic world” from Cairo University (Egypt’s first secular university, founded in 1908), but also sponsored by al-Azhar University (Sunni Islam’s most prestigious center of learning, established by the Shi’ite Fatimid dynasty in the 10th century). Not only was the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood’s leadership invited to attend, but to sit in the front row — thus excluding Obama’s official host (according to protocol) — President Mubarak.

Essentially, this meant that the president of the United States invited the heads of an illegal revolutionary organization to be not only present, but front and center, when he delivered a historic speech of global reach in the capital of a key ally. Thus, the president of that key allied country, whom Obama called a “friend,” could not possibly attend. By this dramatic act, he essentially elevated these criminal elements to the level of a shadow government. Thus, in effect, he was saying to the MB, “You are the future.” At the same time, he was telling our long-time, largely reliable ally Mubarak that he was already virtual history. And this message was not lost upon any of them, even if it was missed entirely by nearly everyone else — especially those who should have seen it easily.

Just as importantly, Obama’s speech was not addressed to a recognized diplomatic entity. The Muslim world is a religious and cultural concept, one that spans dozens of countries around the world, all quite different from each other: it has no broad geo-political unity. Thus — in another first for an American president — he asked Muslims everywhere to define themselves not by national or even ethnic identity, but by their religion. This idea resonates very closely with his flattering (and equally unprecedented) recognition of the globally-subversive Muslim Brotherhood. This too was noted by only a few back home — but it was obvious to those he intended to reach, and to those it most adversely affected, too.

The New, Improved (Democratic) Despot

To America’s mainstream media (The New York Times above all), policy makers and many specialists on the Middle East, President Mursi is the new, improved (because popularly-elected) Hosni Mubarak. On August 26, a front-page NYT assessment of Mursi’s diplomacy by Cairo correspondent David D. Kirkpatrick implicitly cast him as a brilliant new player on the world stage, who despite his lack of experience, has shown his independence of Washington (seen as a positive quality) by going for more diversified international support. Not only had he asked for more aid from Europe, Kirkpatrick enthused, but has also from China and, has even reached out to Mubarak’s (and America’s) bête noire, Iran (both of which he was to visit in late August). Kirkpatrick’s real message can be seen in his approving quotation of an expert’s opinion: “Egypt has credibility as ‘an emerging player in the Arab world and a somewhat successful model of a democratic transition in the Arab Spring,’ said Mr. [Peter] Harling of the International Crisis Group.”

But the climax of Mursi’s international cachet came in November, when Mursi posed as the honest broker — a traditional American role that Obama outsourced to Islamist Egypt — in the search for a ceasefire in a fierce flare-up between Israel and Hamas in Gaza. Hailed as a peacemaker for hammering out a deal that shook dangerous concessions out of Israel (relaxing restrictions on Gaza that may allow more dangerous weapons inside, and an end to targeted killing of terrorists), Mursi is now touted as a pragmatic preserver of Arab-Israeli peace — while America overlooks his dictatorial excesses. That is what critics said about American relations with Mubarak (who tolerated or even encouraged anti-Semitic sentiment in Egypt’s media as a safety valve that allowed him to keep the peace on the ground, rather than openly espousing it himself.) Yet the irony is lost on both the U.S. administration and most of the media as well.

In reality, since joining the Muslim Brotherhood during his days as an engineering student at the University of Southern California in the 1980s, Mursi has been part of an organization dedicated to destroying Israel — and the United States too, and to killing all the Jews in the world as the fulfillment of God’s will. For decades before he became Egypt’s president, he was one of the key leaders in the MB, the hard-line ideological enforcer who purged many more liberal members from the group. He has often spoken of his devotion to jihad, and cheered fellow militants as they spoke of liberating Jerusalem and Gaza and threatened fearsome retribution to the Jews. That is hardly apt to change now that he is head of state — and when a leading member of the MB recently told a local television interviewer that Mursi is still completely under the orders of the group’s murshid, or Supreme Guide, Mohammed Badie. In October 2010, Badie declared the MB’s open support for the global jihad against Israel and America. At least twice since Mursi’s election as president, he has called for jihad against Israel and the Jews.

In January, The New York Times reported remarks that Mursi had made in 2010 — two years before he became his country’s president — referring to Jews as “apes and pigs,” first brought to light by the Washington-based translation service, MEMRI, which monitors statements made in numerous languages by figures via mass media in the Muslim world. Shortly afterward, another MEMRI report revealed that, also in 2010, Mursi had exhorted a crowd in his hometown of Zagazig in the Delta, “Dear brothers, we must not forget to nurse our children and grandchildren on hatred toward those Zionists and Jews, and all those who support them.” He went on to call Obama a liar, based on his failure to live up to the grand promises of good will toward the Muslims in his Cairo speech. These comments reflect essential elements of the MB’s ideology that it has preached since its founding, as well as Mursi’s personal worldview. The White House spokesman, Jay Carney, expressed dismay at them — then went on to imply that since assuming office, Mursi had shown that he didn’t really mean them. (Predictably, the NYT took a similar tack.)

An almost amusing postscript occurred when a group of U.S. senators — including John McCain and Lindsay Graham, among others — queried Mursi about those remarks during a recent visit to Cairo. Mursi tried to explain that the American media, which are “controlled by certain forces,” were to blame for blowing them out of proportion. The senators reportedly “recoiled” at this suggestion, and pressed him repeatedly if by “certain forces” he had meant the Jews. He kept dodging their questions until they finally gave up, but the bad taste remained. But the senators present have yet to demand that aid to Egypt be stopped or even changed. McCain reportedly even requested that the U.S. funnel another $480 million dollars to Mursi’s government after that testy — and presumably eye-opening — encounter.

As Barry Rubin has noted, many in Washington are treating these routine statements of basic beliefs by Mursi as isolated incidents that can be dismissed as aberrations. But a prominent Egyptian columnist, Abdel Latif El-Menawy, in a January 21 column on alarabiya.net,[2] has documented numerous instances in which Mursi personally has said similar things earlier.

Moreover, just a few months prior to the “apes and pigs” flap, MEMRI had posted a current video clip of Mursi (as president) sitting in a mosque in Mansoura in the Delta, in which an imam preaches from the minbar (the Muslim equivalent of the pulpit) for the destruction of all Jews, and of Israel and the United States. As he speaks, Mursi’s gestures and facial expression clearly signal assent to what is being said as he prays in the front row of the squatting congregation.

Nonetheless, Mursi is content to let us delude ourselves about who he really is and what he wants to do — until he feels secure enough to finally drop his mask (one he has only worn when facing West). Until then, he will continue soaking up all the money and military technology that our government will throw at him, gathering the strength that could set him free at last. Meanwhile, he’s expecting $4.8 billion from the IMF (delayed until he can implement his economic reform program), $5 billion in emergency aid from the European Union, plus several billions more each from Saudi Arabia and Qatar (which has also pledged to invest $18.5 billion in Egypt’s economy in the next several years, adding that $2.5 billion would be transferred immediately). In addition, Mursi has asked for $3 billion from China just for his soon-to-be-expanded nuclear program (with an offer of technical and perhaps other assistance from Iran). If he is able to stabilize these arrangements (which are more important to his strategic view than the problem of stabilizing Egypt’s economy), he really won’t need our $1.6 billion aid tied to the 1979 Peace Treaty with Israel (except for the elements of new military technology and maintenance). He may well reach that point soon: the IMF deal may open further lines of credit — and its failure will not prevent others from trying to save the people of Egypt by propping up Mursi.

That Mursi is demonstrably more dictatorial than Mubarak doesn’t seem to faze his donors, real or potential. On November 22, he granted himself powers more immense than those enjoyed by Egypt’s rulers in all of the nation’s five thousand years of Pharaonic-style rule. Yet just as he did during the 2009 democracy demonstrations in Iran, our president said little: on December 6 [2012], he phoned Mursi to express his “concern” and to urge him to engage the opposition in dialogue. There were no reported threats of consequences if Mursi did not comply. He might at least have noted that he had asked Congress for $1 billion dollars in debt relief for the country, to help her weather the worst financial crisis in that country’s modern history — the economic price of overthrowing Mubarak. Meanwhile, Mursi awaits delivery of two Class 209 diesel-electric submarines from Germany — which Israel fears (quite reasonably) will be used to menace her developing gas and oil fields in the Mediterranean — for a price of $1 billion.

Clearly it was not Obama, but the massive protests that his decree — and the blatantly Islamist draft Constitution it was meant to help see through the referendum — that led Mursi on December 9 to cancel most of the powers he gave himself in the declaration. The opposition had demanded that he cancel both. As such it was a meaningless compromise, meant to suck the oxygen out of the opposition, while preserving the most important goal of that decree: the Constitution’s ratification. Meanwhile the army retains its pose as a neutral guardian of the nation, though in effect it has really been protecting Mursi and his goals. Thus it is beyond the reach of U.S. persuasion — should it ever be seriously tried. As the demonstrations against the Constitution reached their peak in mid-December, the SCAF called for dialogue with the opposition — and in so doing was merely echoing Mursi’s own, obviously hollow appeals. (In other words, the army, which the U.S. hoped would be a check on any of Mursi’s excesses, simply is no longer willing or able to play that role — if it ever really was.)

Contrast this with Obama’s fateful statement that hastened Mubarak’s fall from power. But since Mursi’s August 12 purge of Mubarak-era leaders in the military (ironically facilitated by Washington, in the interest of further speeding that “transition to democracy”), and with his diversification of foreign aid — radically reducing his dependence on the U.S. — it is doubtful that Obama has any ability to do that again. Nor would he want to replace Mursi, the elected president (who has shown a complete lack of democratic scruples and whom at least half of Egypt feels has lost his legitimacy) anyway.

In a September 24 interview for PBS, Mursi — then in New York for the annual opening of the U.N. General Assembly — was asked by Charlie Rose if Egypt really was (still) an ally. “The U.S. president says otherwise,” he shot back (referring to his American counterpart’s remark that Egypt was no longer an ally, uttered a few days earlier in exasperation with Mursi’s slow response to the incident at our embassy on September 11). He then explained that, “This depends on how you define an ally.” He clarified that while Egypt may still be an economic or political partner of the U.S., “the understanding of an ally as part of a military alliance — that does not exist right now.” Given that the vast majority of American aid to Egypt is military, this is an extraordinary declaration that should have led to an immediate review of the bi-lateral relationship. He added that it is better to be friends than allies (although “friend” is a diplomatically insubstantial term).

In the same, almost completely unremarked (and shockingly fawning) interview during Mursi’s visit to the United Nations General Assembly in New York spoke of his compatriots’ widespread “hatred” of the U.S. And he defended their right to express that hatred by demonstrating at the U.S. embassy in Cairo, where a mob — in a pre-planned, not spontaneous, protest organized by the MB and al-Gama’a al-Islamiya (the Islamic Group) — went over an outer wall, burned an American flag flying there, and replaced it with the black jihadi banner used by al-Qa’ida and its affiliates. (Falsely, he claimed in the interview to have protected the embassy, but such an outrage could not have happened under Mubarak. Mursi also tweeted messages in Arabic that incited the protesters: one said, “The noble Prophet Muhammad — may God bless him and grant him salvation — is a red line: whoever transgresses against him, we shall treat as an enemy.”) Rose asked him about a reportedly “heated” call that Obama had made to declare his concern about Mursi’s slowness to denounce the incident. (Speaking of that event, outgoing Secretary of State Hillary Clinton told the Senate Intelligence Committees on January 23: “With Cairo, we had to call them and tell them, ‘Get your people out there.'” Mursi hastened to say that their conversation was “warm, it was not hot.” When Rose wondered if Obama had threatened to cut off U.S. aid, Mursi said, “There was no threat of any kind.”)

Left unsaid in that interview — or almost anywhere else — is that protest against alleged defamation of the Prophet in the “Innocents of Muslims” movie trailer was only one of two reasons for the several days of demonstrations that besieged our embassy in Egypt last September. The other was to demand the release of the “Blind Sheikh,” Omar Abdel-Rahman, head of al-Gama’a al-Islamiya and mastermind of the 1981 assassination of Mubarak’s predecessor, Anwar al-Sadat; of the Islamist insurgency in Egypt in the 1990s that claimed a thousand lives (including scores of foreign tourists), of the 1993 World Trade Center Bombing, and whose fatwas provided the justification for the 1992 killing of Egyptian anti-Islamist activist Farag Foda, the 1994 attempted murder of Egyptian Nobel laureate in literature Naguib Mahfouz, and for the attacks of September 11, 2001 in the U.S.

Osama bin Laden is believed to have funded al-Gama’a al-Islamiya, beginning in the 1990s. A major figure in the protests against our embassy was Mohammed al-Zawahiri, brother of current al-Qa’ida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, released from prison in Egypt in March 2012. Mursi has personally pardoned dozens of other jihadis convicted of terrorist murders in Egypt. Among them was Mustafa Hamza, who directed al-Gama’a al-Islamiya’s attempt to assassinate Mubarak in Addis Ababa in 1996, and the cell that killed 58 foreign tourists and four Egyptians at Hatshepsut’s Temple in Luxor in 1997 from Afghanistan. (His family is said to have been given safe haven in Mashhad, Iran.) Is it any surprise, then, that Mursi has denounced the current French military operations aimed at reversing the jihadi conquest of Mali?

The Majority of a Minority Rules

The referendum on Egypt’s draft Constitution was held in two stages — on December 15 and 22, divided according to region — passed officially with 63.8 percent of the votes. Though the first round included both Cairo and Alexandria, where the majority of secularists live, the Islamist document won 56.5 percent that day. The second round, on December 22, held mainly in areas where Islamist support is strongest, resulted in a total “Yes” vote of 63.8%. Even as the balloting began, opponents of the charter were still fecklessly debating whether to vote against it or boycott the referendum. That, of course, means the votes themselves are not an accurate reflection of sentiment against it. Turnout for both rounds was low — a total of only 33 percent — down from 43.4 percent in the presidential elections last spring. (That itself was much less than the 54 percent who took part in the 2011-2012 parliamentary elections before them.) Many Egyptians, it seemed, would rather fight than vote. Moreover, with illiteracy said to be at 45 percent (and probably much higher), roughly half the public could not read the long, rambling text (49 pages, 234 articles)[3] — nor anything else for that matter.

Though pundits have cautioned that “turmoil” will continue, many assumed that, with the referendum, Egypt has finally completed its nearly two-year transition to “democracy.” Yet the result will actually bear little resemblance to the sort of democracy deliriously expected by so many around the world when Mubarak fell. Among those Egyptians so far vainly battling the Islamist tide, more than a few now rue the revolution as a mistake — and a fatal one at that. Again, that should have been obvious too (as it was to a widely-excoriated few).

However, a glimmer of hope has arisen from a spontaneous uprising that began in Port Said on January 26, launched by people furious at death sentences unexpectedly handed down that day to relatives of theirs for involvement in a riot that left 72 dead at a soccer game there last year. The current melee soon engulfed two other cities along the Canal — Suez and Ismailia. All three are now under curfew in a month-long state of emergency: perhaps a hundred persons have since died in clashes with the police. (In Egyptian society, nothing — not even revolutionary politics — inflames passions so much as either football or family honor and revenge.) In Port Said itself, for the first time, there are reliable reports of gunfire coming from anti-government rioters. However, much of the anti-Mursi opposition has distanced itself from these events, and it is unclear if a united political front will spring up to capitalize on the chaos. Perhaps ominously, a masked group of alleged anarchists, the Black Bloc, which appeared as a new force in the mix of organizations standing up to the chief executive’s followers, the “Mursistas,” over the past few months — is blamed for much of the bloodshed in latest crisis. And on January 30, the U.S. embassy in Cairo suspended all services after the looting of the luxury Semiramis Intercontinental Hotel next door the day before. As all this unfolds, the combination of the threat to Egypt’s all-important Suez Canal revenues with the ongoing protests across Egypt has prompted the Mursi-appointed Army Chief of Staff, General Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi, to warn on January 29 that unless some sort of political consensus is reached in the country, “the state could collapse.”

Yet, while certainly more intense and widespread, the uproar is not new. In the weeks running up to the referendum, mass demonstrations tore traditionally calm Egypt apart, violent clashes leaving dead on both sides. Throughout this period the Islamists once again proved themselves to be more organized, ruthless and determined. Though both Mursi’s backers and foes have their own shock troops formed mainly out of football hooligans called Ultras, the Islamists apparently have been the only side to have used firearms (excluding, evidently, what has since happened in Port Said) and reportedly even roving bands of thugs and rapists on their enemies. They have assaulted Christians and women particularly, including acid attacks on unveiled women in Alexandria. This accompanied an alleged drive to block all unveiled women (who are presumed to be Christians, or else lax Muslims) from voting in that city. Most of the nation’s jurists refused to oversee the balloting, with just enough cooperating to give it a veneer of legitimacy, and to make up the core of the new, Islamist judiciary that will likely follow Mursi’s victory.

The catalog of the Islamist government’s tyrannies has been increasingly impressive. In December, the state prosecutor began to investigate the three top opposition leaders, the heads of the National Salvation Front: Mohammed ElBaradei (ex-Secretary General of the International Atomic Energy Agency), Amr Moussa (former head of the Arab League) and Hamdeen Sabahy (a hard-left activist with Islamist connections who came in third in the first-round presidential vote last year) on suspicion of plotting to kill Mursi. And now he is looking at comedian BassemYousef (often called “Egypt’s Jon Stewart”) on a possible charge of insulting Mursi: to defame any leading public figure is a crime under the new Constitution.

Nonetheless, despite the openly Islamist and dictatorial character of the MB regime, both America and Europe remain uncritically supportive. The IMF is concerned only about Egypt’s economic policies as justification for its loan; the European Union seems to have no pre-conditions at all for its aid. Shockingly, neither does the United States, which — unlike these other institutions — provides Egypt with military aid. Heedless of the dangers of continuing such a relationship with an Islamist regime, the U.S. has not simply failed to cut off its funding. At time of writing, the first four of sixteen F-16s promised to Mubarak at time of writing are en route with an understanding that the rest of the order will be filled. (We are also giving him two hundred Abrams tanks in the same package.) On January 26, Mursi called the F-16s a sign of support for his rule — as it most surely is.

Massacre of the Benefactors

Obama’s dramatic and persistent outreach to the MB, that began at the latest in June 2009, continuing throughout the 2011 revolt and transition and beyond, makes him at the very least a co-author of the Egyptian revolution, and even of the Arab Spring. Indeed, the entire phenomenon arguably could not have happened and unfolded as it did without him. (And in a different sense, it would not have taken off without the previous democracy drive in the region under his predecessor, George W. Bush.) Obama, interviewed (very softly, a la Charlie Rose) with Secretary Clinton on the CBS program “Sixty Minutes” on January 27, bragged to Steve Kroft, “You know, when it comes to Egypt, I think, had it not been for the leadership we showed, you might have seen a different outcome there.”

Mursi certainly ought to thank Obama for empowering him and the MB. But Mursi’s offer of “friendship” (not alliance) as per his interview with Charlie Rose, is similar to an invitation to the Americans to a dinner in which they and their allies will be on the menu.

Arab history is full of tales of massacres of whole dynasties at meetings of friendship. Among the most famous occurred on June 25, 750, when the victorious Abbasid commander Abu al-Abbas Abdullah invited some eighty surviving members of the Umayyad family they had overthrown in Damascus to a banquet of reconciliation at Abu Futrus near Jaffa. Soon after the meal began, assassins struck down the unsuspecting princes in a serial slaughter. As many of them lay still groaning, leather covers were thrown over them, and the dinner continued as before.

Also famous, on March 1, 1811, Muhammad Ali Pasha, later the founder of Egypt’s last royal dynasty, invited four hundred and seventy members of the former ruling caste, the renowned fighting Mamluks — who persisted as his rivals — to the Citadel of Salah al-Din in Cairo. After taking coffee with them, the pasha saw off his guests as they rode out of the fortress through a narrow defile toward al-Azab Gate. Abruptly the gate closed before them, as marksmen fired down on them from the walls on either side. The noble Mamluks, Islam’s most storied cavalry, galloped their horses back and forth frantically in search of a means of escape — but there was none.

We are now being asked to a banquet by enemies posing as friends, offering a meal that we have paid for with our own treasure. This is not a banquet of food, however, but a feast of phony democracy that we have called the Arab Spring. We shall be seated at a table that we have provided, and butchered with our own arms as we imbibe the wine of false accomplishment. Meanwhile our hosts — our erstwhile protégés — will carry on the party over our corpses.

And once more as in my earlier E-Note — written as Mursi was on the eve of winning his battle with old Mubarak appointees in the military for control last August — we again have a choice: we can either succumb to the charms of the “moderate Islamists,” or wisely begin to refuse them at last. All of the aid and recognition we give to these crafty zealots only whets their appetite for more. Their entire history points to this: nothing they say or do, in order to fool those suspicious of them, should ever make us forget who they really are, and what they have always stood for.

If we do, then we shall have forgotten what we stand for too.

Raymond Stock resided in Egypt for 20 years. He is writing a biography of Egyptian Nobel laureate in literature, Naguib Mahfouz (seven of whose books he has translated), for Farrar, Straus & Giroux in New York. A 2007 Guggenheim Fellow, with a Ph.D. in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations from the University of Pennsylvania, his articles and translations of Arabic fiction have appeared via Bookforum, The Financial Times, Harper’s Magazine, International Herald Tribune, FPRI E-Notes, Middle East Quarterly, and many other venues. His translation of Mahfouz’s novel Before the Throne appeared in paperback via Anchor Books/Random House in July 2012. A former Visiting Assistant Professor of Arabic and Middle East Studies at Drew University, he is currently a Shillman/Ginsburg Writing Fellow at the Middle East Forum.

![]()

Notes:

[1] Raymond Stock, “The Donkey, the Camel and the Facebook Scam: How the Muslim Brotherhood Conquered Egypt and Conned the World.” (Philadelphia: Foreign Policy Research Institute, E-Notes, July 2012). This writer speaks at greater length about Egypt and Islamist rule in an interview by Jerry Gordon, “No Blinders about Egypt under Muslim Brotherhood,” New English Review,” November 2012. Yasmine El-Rashidi offers an outstanding current analysis in the February 7, 2013 issue of The New York Review of Books, “Egypt: the Rule of the Brotherhood.”

[2] Abdel Latif El-Menawy, “Mursi Needs to Admit His Real Stance from Zionists.” Al-Arabiya News, January 21, 2013.

[3] You can download the English text of the 2012 Constitution of Egypt here.

RSS

RSS

Latest Comments

Hello Mike, Thank you for your positive feedback to the article. I felt there wasn’t too much critical analysis of ...

Thanks for this considered and well constructed article. A follow up article on the manner in which the editorial contro...

THE CLUELESSNESS OF CLAIMING THAT OBAMA'S MIDDLE EAST POLICIES WERE A FAILURE CANNOT BE FURTHER FROM THE TRUTH, WHAT THE...

As long as Obama is the president of the usa do not trust the us government......

Thank you for an good read....