![]()

Fri, Dec 02, 2011 | Middle East Forum | by Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

Originally published in the Israel National News.

As we approach the end of the first year of what has been called the “Arab Spring,” it is worth examining the nature of Shi’a (Shiite) -Sunni relations in the Middle East. Indeed, commentators such as Patrick Cockburn have been warning that “since the start of the Arab uprisings this year, Shi’a-Sunni hostility has deepened again wherever the two communities seek to live side by side.”

To discuss this issue, a country-by-country survey is useful wherever there are significant Shi’a-Sunni divides in the population.

Iraq: As U.S. troops look set to complete their withdrawal from the country before the end of this month, perhaps leaving only a few hundred to provide further training for the Iraqi security forces, some analysts have raised concern over tensions spilling into another full-blown sectarian civil war. Amongst other things, they draw attention to the recent arrests — on the basis of vague allegations of promoting Baathism — of hundreds of Sunnis in two predominantly Sunni provinces seeking autonomy (Salahaddin and Anbar), the possibility that a civil war in Syria will embolden Iraq’s Sunni Arabs, the continued activity of militant groups like al-Qa’eda, and an apparent proposal among Shi’a and Kurdish politicians to reduce the size of Sunni Arab provinces.

However, such anxieties fail to take into account the primary reason for the decline in violence across the country: namely, that the Sunni Arab community has generally come to realize that it lost the civil war to the Shi’a militias.

Most Sunni insurgents initially thought they could defeat the Shi’a by supposed numerical superiority, yet by the end of 2006 Sunnis had been ethnically cleansed from most mixed neighborhoods in Baghdad.

Observe the demographic shift by examining a map of the capital from 2003 and compare with one from early 2007, just at the time of the start of the surge.

Survival for most Sunni Arabs in Iraq therefore depends on adapting to the fact that the Shi’a are leading the political process in the country.

The problem of militant groups is thus more accurately described as terrorist threats from organizations that also function as criminal gangs also engaging in robberies and extortion, rather than a threat of renewed sectarian civil war.

Yemen: In the wake of President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s transfer of powers on paper, it is notable that an all-out conflict is erupting between the Zaydi Shi’a Houthi rebels, who are primarily based in the north and are aiming to expand their control to gain access to the Red Sea coast, and Salafist Sunni militants. Dozens of fighters have been killed on both sides over the past couple of weeks, with Houthi rebels now reportedly subjecting parts of the Dammaj district of Saada province to artillery shelling.

Meanwhile, as speculation arises over what comes next after Saleh, rebel general Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, commander of the first Armored Division of the Yemeni army, is arguably the most powerful figure in the country, and he is known for his links to Sunni Islamist militants and his anti-Shi’a sentiments.

The Sunni Islamists are also at odds with the increasingly assertive southern separatists, who are generally secular owing to Marxist influences on their ideology.

It has often been supposed that the Houthi rebels have been receiving Iranian support, but there has been no reliable evidence for this assertion so far. Indeed, Iranian backing for Shi’a militants as proxies has occurred on account of geographical proximity (as was the case for Iran’s neighbor Iraq, via Maysan province in the south-east, which has historically been a route for arms smuggling) or through an ally (i.e. Syria as an intermediary for Iranian support for Hizbullah in Lebanon).

Neither of these factors applies to the Houthis, but should these Zaydi Shi’a rebels gain access to the Red Sea, Iran may well begin to provide them with financial aid and weapons in the face of their conflict with the Salafists.

In turn, Saudi Arabia could involve itself and start backing the Sunni militants to contain the Houthis, fearing destabilization along its southern border.

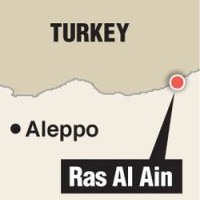

Syria: While Assad clings to power, it is increasingly clear that the country is being divided along sectarian lines, with minority Alawites (who, incidentally, are not strictly Shi’a but have merely defined themselves as such to win solidarity from fellow Shi’a in the region) on the side of the regime — and in control of the elite security forces — versus the Sunni Arab majority.

Numerous reports, for example, have emerged on sectarian killings in the city of Homs, divided sharply between Alawite and Sunni Arab neighborhoods. To be sure, there is still a degree of crossover as many middle-class, urban Sunnis have refrained from joining the protests against Assad, but that could well change in the near future as the state of Syria’s economy hangs in balance.

Two primary mitigating factors against economic sanctions from the outside world are Iraq’s close trade ties with Syria, and Iran’s reported purchasing of Syrian crude oil (although the Iranians deny it).

The Syrian National Council (SNC), with strong Turkish support, has come to be dominated by Sunni Islamists, and members of the Free Syrian Army have begun to receive training from prominent Islamists like Belhaj, commander of the Tripoli Military Council in Libya.

In the meantime, as the Wall Street Journal reports, “Christians already speak of arming themselves. Ethnic Druze say they have made underground bunkers in their rugged southwest mountains.” Both of these minorities are evidently not siding with the opposition; for instance, Christian leaders in Syria like Melkite Greek Catholic Patriarch Gregory III Laham have condemned the Arab League’s suspension of Syria from the organization and imposition of sanctions on Assad’s regime.

On the other hand, the Kurds remain divided, with many still suspicious of the Sunni Arabs in the SNC and their ties to Turkey. Assad has attempted to exploit this by trying to reach out to the Kurds in the country’s northeast.

An end to the conflict is unlikely in the near future, but a full-blown sectarian civil war could be avoided if an Alawite general overthrows Assad by means of a military coup, although there is no sign yet of such a development’s taking place.

Should sectarian civil war break out, many Alawite activists are hoping that their community can at least salvage an autonomous province in the northwest along the lines of the “Alawite State” that existed under the French mandate of Syria after the First World War. However, it remains questionable whether the Sunni Arabs would generally tolerate such an arrangement, for a de facto partition of Syria in such a way would cut off their access to the Mediterranean Sea via the country’s principal port city of Latakia, and therefore hamper the chances of their having a viable economic future.

Hence, in the event of a sectarian civil war, expect significant bloodshed, not exactly like Iraq in 2006 where the fighting raged for control of one city but undoubtedly with similar scale of loss of civilian life.

Lebanon: It is clear that the unrest in Syria is having repercussions in Lebanon. As the New York Times notes, “for the Future Movement, which has been dealt major blows by March 14’s (anti-Syrian coalition) loss of control of the government and the physical absence from Lebanon of its leader, former Prime Minister Saad Hariri, the Syrian uprising has provided an opportunity to rejuvenate its support base, which is largely Sunni.”

This attempt at rejuvenation included, for example, a rally recently organized by Saad Hariri’s party in the northern city of Tripoli and involving thousands of people, with some waving the flag of the Syrian opposition. The primary purpose of the protest was to commemorate Lebanese politicians murdered by pro-Syrian agents in recent years.

Yet the picture in Lebanon is not quite as simple as one of just Sunnis against Shi’a. For the March 8 alliance (the pro-Syrian coalition, including Hizbullah and Michel Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement, which is primarily Maronite) — embodying ‘resistance’ ideology also espoused by Assad — is apparently beginning to crack.

Najib Mikati, the Lebanese Prime Minister installed by the March 8 alliance at the start of this year, has threatened to resign if the present government does not provide funding for the UN-backed Special Tribunal on Lebanon, which has been investigating the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri and has thus far indicted four senior members of Hizbullah. Unsurprisingly, Hizbullah has come out in opposition to Mikati’s sentiments, but as Michael Totten points out, Mikati has never liked Hizbullah anyway, being quoted in a Wikileaks cable as describing Hizbullah as “cancerous.”

All that said, a civil war in Syria might lead to sporadic outbreaks of sectarian violence in Lebanon, while an end to the Assad regime together with the ascendancy of a Sunni-dominated regime will undoubtedly end the sense of intimidation many Lebanese Sunnis feel at the hands of an armed Hizbullah. The latter, deprived of its primary support in the event of Assad’s downfall, may feel a need to reach a compromise with the Sunni community as a whole if it wishes to avert a second Lebanese civil war.

Recall that the main consequence of the first civil war in Lebanon, though multi-faceted, was the reduction of Christian influence in the country, rather than a shift in the balance of power between the Shi’a and Sunnis.

Bahrain: I have previously noted that one of the causes of increasing sectarian tensions between the Shi’a majority primarily comprising the Bahraini protestors and the Sunni minority regime has been the latter’s failure – reinforced by the Gulf Cooperation Council’s intervention – to distinguish between pro-Iranian Islamists like Hassan Mushaima of al-Haq and more mainstream factions such as al-Wefaq.

There is no good evidence for Iranian interference in the protests thus far, despite Iranian claims to Bahrain as its fourteenth province. In any case, in the wake of the publication of a report by the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry, both sides are only becoming more and more impervious to compromise and therefore squandering opportunities to restore stability.

Even as they face criticism from the commission’s report, the security forces continue to engage in violent crackdown against Bahraini protestors, while al-Wefaq has refused to participate in the National Committee, recently set up to discuss the commission’s suggestions and reports its findings to the monarch by February. As Hussein Ibish notes:

“This mirrors its stance of boycotting parliamentary balloting in September and refusing to participate in the legislature under the current circumstances. One can readily understand the opposition’s skepticism about the government’s intentions and this entire process. However, the commission report was hardly the whitewash that many opposition figures had predicted. To the contrary, it was surprisingly blunt about the excessive use of force and other abuses on the part of security services, even though it did not go as far as many would have wanted with regard to the systematic nature of abuses.”

Saudi Arabia: It has recently been reported that protests have arisen in the predominantly Shi’a areas of the eastern half of the country, where the population, suffering considerable discrimination, has not received a fair share of the nation’s oil wealth even though the eastern provinces contain the biggest oil fields. As a result, many protestors in towns like Qatif have been chanting, “Death to [the house of] al-Saud!” (in reference to the dictatorial, ruling royal family).

The Saudi security forces have responded by firing on demonstrators, killing several unarmed people. Saudi Arabia has unsurprisingly accused the protests of being part of an Iranian plot, while al-Jazeera‘s Arabic channel, in keeping with its anti-Shi’a bias, accused the protestors of aggression and portrayed the casualties as merely the result of crossfire. Al-Arabiya parroted the official Saudi line. In any event, there is no evidence that these protests are being driven by Iran.

In fact, if polling data by Pechter Middle East Polls are a reliable indication of public opinion in Saudi Arabia, it is actually the primarily Shi’a residents in the eastern area of al-Ahsa who most fear Tehran’s ambitions in the region, as opposed to their Sunni neighbors in the western half of the country, and accordingly they are more inclined to support an American pre-emptive strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities.

Summing Up: In sum, sectarianism has become more entrenched in the Middle East since the “Arab Spring” first began. Syria and Yemen are the most likely candidates for full-blown Shi’a-Sunni civil wars of some sort, yet it need not necessarily be thought that such conflicts, if they arise, will resonate across the region so as to trigger a regional Shi’a-Sunni civil war. Iraq is almost certainly going to remain immune from such a danger, given the country’s experiences over the past years.

Nor should it be presumed that every area with Sunni-Shi’a tensions entails a proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran respectively, though such a scenario could well emerge in Yemen in the near future.

Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi is a student at Brasenose College, Oxford University, and an intern at the Middle East Forum.

RSS

RSS

Overviewing Shi’a-Sunni Conflicts | Middle East, Israel, Arab World, Southwest Asia, Maghreb http://t.co/pzt0jg5l

Overviewing Shi’a-Sunni Conflicts | Middle East, Israel, Arab World, Southwest Asia, Maghreb http://t.co/pzt0jg5l