![]()

Mon, June 11, 2012 | By Halil M. Karaveli

This article was first published in the Turkey Analyst, vol. 5 no. 12 (www.turkeyanalyst.org), a biweekly publication of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center. © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center, 2012.

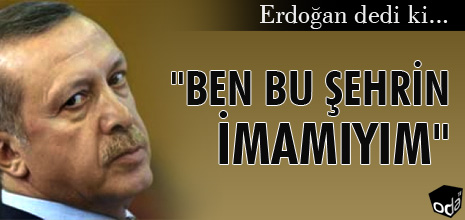

Erdogan Sees Himself as the “Imam” of Turkey, But is the AKP’s New-Old Islamism a Recipe for Success?

It is becoming increasingly obvious that Turkey’ ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) is reverting to its Islamist roots. Flexing his Islamist muscles, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan expects to keep the conservative core constituency mobilized behind him. However, the AKP’s new-old Islamism is in fact not in tune with the dynamics of societal change that has upheld its power until now. The attempt to institute another regime of tutelage, this one Islamic, is bound to alienate crucial constituencies for the AKP — the liberal seculars, obviously, but modern conservatives as well. The AKP seems set to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

Background

The AKP has been the vehicle of an unprecedented change in Turkey’s modern history; the party has, as Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan recently noted with pride, accomplished a “silent revolution” since it came to power a decade ago. Once a country where the generals were all powerful, and where the economy was in deep crisis, Turkey has changed beyond recognition. The AKP itself has embodied change: the founders of the party had broken ranks with the Islamist movement of Turkey, and presented themselves as “conservative democrats”, in the image of European Christian democrats.

Erdoğan has been rewarded by the electorate for his successful management of the economy — Turkey is now the 16th largest economy in the world — and for having put an end to military tutelage. The AKP has spearheaded what by all accounts represents a dramatic change — but it has in turn also benefited from the change of attitudes in society. Not only did a majority in Turkey hold the military in the highest of esteem just a few years ago, but there was also a broad support in society for the right of the military to intervene in politics and to stage coups if necessary; that support has by now all but evaporated. According to a recent survey, the notion that a military coup can be legitimate has become an opinion only held by a minority. The AKP has been successful because it has embodied change and because it has tapped into the dynamics of change in society. But now the evidence is accumulating that the AKP had in fact not changed, as the ruling party is reverting to its Islamist roots.

“The suspicions that post-Kemalist Turkey is not going to evolve toward a fully democratic country are growing”, writes İhsan Dağı, a prominent liberal intellectual, in the daily Zaman, the media flagship of the movement associated with the Islamic cleric Fethullah Gülen. Şahin Alpay, another academic and columnist in Zaman, warns that the AKP will fall from power if it does not change course.

What ultimately brought about the downfall of the regime of military tutelage, and of the Kemalist ideology that had legitimated the rule of the generals, was the dynamism of Turkish society; it had become too dynamic, too diverse to be contained by the strait-jacket of a semi-authoritarian state. Room had to be made for the aspirations of a rising, pious middle class, while the resistance of the Kurds to oppression had contributed significantly to sapping the strength and confidence of the state. But as the ongoing arrests of Kurdish politicians make clear — thousands of activists and hundreds of elected officials have been imprisoned since the wave of mass arrests began in 2009 — the new masters of Turkey are intent on pacifying rather than accommodating the Kurdish movement. Most recently, on June 10, the mayor, who represents the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), of the town of Van was arrested, charged with “membership of a terrorist organization”.

While the ruling AKP has inherited the authoritarian nationalism of the Kemalist regime, it is increasingly also succumbing to the temptation to engage in its own version of social engineering, seeking to remold society according to a rigidly conservative blueprint. The recent overhaul of the school system, which introduces a stronger religious component into education, reveals that Erdogan was indeed being serious when he vowed that “we are going to raise pious generations”. Concerns of a conservative, authoritarian drift have further been heightened after the recent announcement of Erdoğan that the government is preparing to introduce a bill that will outlaw abortion. Stating that “abortion is murder”, the prime minister also expressed his disapprobation of the practice, which is widespread, of caesarean births.

When asked by journalists why he felt the need to pronounce himself on the latter issue, Erdoğan replied that “as prime minister, everything in this country is my responsibility”. Erdoğan, as well as other AKP officials, has recently also expressed his disapprobation of the “immoral” repertoire of the public theatres in Istanbul. The AKP government is planning to privatize the public theatres as punishment, which has sparked protests. Speaking about actors and intellectuals in general in disparaging terms, notably accusing them of being alien to the culture of the people, Erdoğan stated that “if we like something, then we’ll fund it”.

Implications

The growing attention that the AKP is paying to enforcing “morality” suggests that Erdoğan had never changed, that he has continued to view himself, not as an ordinary political leader, but as the “imam” of his countrymen, entrusted with a mission to ensure that society is purged of “sin”. Eighteen years ago, when he was the mayor of Istanbul, Erdoğan had in fact expressed that plainly. Shortly after having been elected, Erdoğan had decided that no alcohol was going to be served at a reception at the inauguration of an art exhibition, held on premises that were owned by the municipality. The freshly elected mayor had defended that decision by remarking that “I am not only the mayor of this city, I am also its imam, and as such responsible also for others’ sins.”

Erdoğan is not being as explicit today as he was back in 1994; but the remark that he as prime minister is responsible for everything in the country nonetheless have unmistakable religious connotations as well, beside the apparent authoritarian implication; when Erdoğan, speaking of abortion as “murder” states that “we must make our sisters realize this”, it suggests that he assumes a responsibility for ensuring that his countrymen don’t “sin”.

In yet another symbolically charged move, the AKP government is reportedly about to introduce a bill that will make it mandatory to provide Muslim prayer rooms in opera houses, museums, schools and preschools. And Erdoğan has commissioned a gigantic mosque, to be built on the Asian shore of the Bosporus, that will, he has promised, “going to be visible from all parts of Istanbul”.

Flexing his Islamic muscles, Erdoğan is deliberately keeping the secular-religious divide alive, and the obvious intention is to reinforce the ideological hegemony of the ruling party. The seculars are further demoralized, while he in all likelihood calculates that escalating tensions will concurrently help keep the conservative constituency securely mobilized behind him. Erdoğan has his eyes on the next election; he aspires to become Turkey’s first popularly elected president. Islam, alongside Turkish nationalism, which Erdoğan has also been making abundant use of in his rhetoric, seemingly makes for an unbeatable combination in the quest for the supreme leadership of Turkey.

There can be no doubt that the AKP’s reversion to a rigid, religious conservatism strikes a chord in a society where orthodox religion remains a point of reference. Yet the religious-secular dichotomy that Erdoğan is endeavoring to maintain by taking aim at some of the expressions and symbols of secular modernity — women’s free choice, “immoral” theatres, cultural freedom — nonetheless no longer fully account for the dynamic reality of Turkey.

The change that has taken place during the last decade has blurred some of the distinctions of the past. Erdoğan’s and the AKP’s attempt to impose a “moral” and “religious” order on everyone is in fact an affront to pious Muslims who manage to reconcile modernity and religiosity naturally, who don’t clamor for prayer rooms in opera houses to demonstrate their piety; the version of Islamic order that the AKP is promoting is an almost caricaturized one, confirming the worst preconceptions of Islam. Erdoğan’s statement against women’s right to decide over their own bodies drew sharp criticism not only from secular women, but from young, female Islamic intellectuals as well. Such voices may not be representative of the Muslim mainstream, but they are nonetheless suggestive of the evolving attitudes among the pious; indeed, AKP’s new-old Islamism is not in tune with the dynamism of the religious middle class in Anatolia that has carried the party to, and kept in power.

That middle class may be religiously conservative, but it owes its ascension to the fact that it has transcended national and cultural borders, participating in the global economy. A rigid conservatism that gives Turkish Islam a bad name and which entrenches differences within Turkey, as well as between Turkey and the modern world, is not in the interest of Anatolia’s rising middle class.

Conclusions

The AKP’s reversion to Islamism speaks of an ideological and intellectual paucity; the AKP could have elected to build on the societal trends that had converged to keep the party in power for a decade, but ultimately, the party seems to have run up against its intellectual and ideological limitations.

The future belongs, not to Islamism, but to a party or parties that succeed in tapping into those dynamics of change that work to reconcile religiosity and modernity and secularism and democracy, respectively.

The AKP’s greatest victory to date, the referendum on September 12, 2010, when six of ten voters approved the constitutional amendments that put an end to the Kemalist regime of tutelage, demonstrated the breadth of the coalition for change. The attempt to institute another regime of tutelage, this one Islamic, is bound to alienate those crucial constituencies for reform — the liberal seculars, obviously, but modern conservatives as well. The AKP seems set to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

Halil M. Karaveli is Senior Fellow and the Managing Editor of theTurkey Analyst at the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center.

RSS

RSS

Latest Comments

Hello Mike, Thank you for your positive feedback to the article. I felt there wasn’t too much critical analysis of ...

Thanks for this considered and well constructed article. A follow up article on the manner in which the editorial contro...

THE CLUELESSNESS OF CLAIMING THAT OBAMA'S MIDDLE EAST POLICIES WERE A FAILURE CANNOT BE FURTHER FROM THE TRUTH, WHAT THE...

As long as Obama is the president of the usa do not trust the us government......

Thank you for an good read....