![]()

Tue, Nov 01, 2011 | Middle East Forum | The American Spectator | by Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

Sudan in Crisis

Three months after the birth of South Sudan, how is the northern neighbor of the world’s newest nation faring?

The country, witnessing minor demonstrations, generally managed to escape the large-scale protests that have swept across the Middle East and North Africa since last winter, but as the Financial Times reports, Sudan’s economy has been hit severely by the secession of the south, which was by far Khartoum’s largest source of oil revenues.

Indeed, the oil boom in the early 2000s made Sudan one of the fastest growing economies in Africa. Yet owing to a 75 percent drop in oil revenues since July, the Sudanese pound — Khartoum’s currency — has dropped by up to 60 percent on the black market, while annual inflation reached 21 percent last month, with the price of meat now reaching $10 per kilogram. Of course, these developments could well re-ignite popular protests.

Meanwhile, the ruling autocrat Omar al-Bashir has vowed to adopt a constitution completely in accordance with Sharia (Islamic law). As Bashir himself put it, “Ninety-eight percent of the people are Muslims and the new constitution will reflect this. The official religion will be Islam and Islamic law the main source [of the constitution].”

This statement neatly fits in with his outlook elaborated on in December of last year, when he declared: “If south Sudan secedes, we will change the constitution and at that time there will be no time to speak of diversity of culture and ethnicity.… Shari’a and Islam will be the main source for the constitution, Islam the official religion and Arabic the official language.”

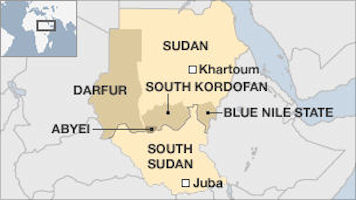

This will naturally pose problems for the million or so southerners still residing in the north, as well as the Christian populations residing in Sudan’s southern border states of Blue Nile and South Kordofan, both of which were granted a degree of autonomy on religious and cultural issues as part of the 2005 peace deal that recognized the “cultural and social diversity of the Sudanese people.”

While the Catholic Church in Blue Nile did not hesitate to voice its anxieties back in February over a potential extension of Shari’a law, it is disconcerting to note that Bashir’s initiative apparently has strong support from local Muslims in Blue Nile.

In fact, Blue Nile and South Kordofan merit special attention because the Sudanese government is still waging an active, indiscriminate bombing campaign in these areas against rebels who, consisting of Christians and some Muslims, belong to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N). South Kordofan, situated in the Nuba Mountains, contains a substantial proportion of Sudan’s remaining oil reserves, and by August had already seen the displacement of nearly 400,000 civilians, amid claims of rebel advances against government troops.

As for Blue Nile, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that more than 27,000 refugees have fled into neighboring Ethiopia as a result of the conflict, and state media are reporting that the Sudanese army is closing in on the rebels as it has seized control of the town of Sali, just 5.6 miles north of the rebel stronghold of Kurmuk, which has been almost completely emptied of civilians. On the other hand, the SPLM-N is denying that this event has occurred.

Precise information as to the balance of power in the fighting in Blue Nile and South Kordofan is difficult to obtain because aid agencies have been denied access to both areas. Hence, the U.S. Special Envoy to Sudan — Princeton Lyman — has called on Khartoum to allow “credible” international NGOs to reach the two states to assess the humanitarian situation.

In any event, it is clear that the events in the two border-states could well provoke a war between Sudan and its southern neighbor, with the former accusing the latter of orchestrating the rebels’ activities. South Sudan denies this allegation, but may feel compelled to support the SPLM-N in the near future should Khartoum’s forces overwhelm the rebels and carry out mass killings on a similar scale to what happened in Darfur.

At this point, many are inclined to dismiss the role of the Sudanese government’s Islamist and Arab supremacist ideology behind its policies in South Kordofan and Darfur. Granted, there is a desire to secure a monopoly for Khartoum itself (where much of the wealth from the oil boom years was spent for the benefit of the Arab elite in the capital city) on the country’s remaining petroleum reserves.

However, the regime’s key goal of imposing Islamic law and Arabization on the Christian and black African Muslim ethnic groups in the country is evident from the statements made by the Sudanese elite. Bashir’s desire to extend the realm of Sharia and enforce an Arab identity over the entire country has already been noted.

When it comes to Darfur, where an inflow of arms from Libya could now revive the Darfuri rebels’ fight against the government, Sudanese officials and Janjaweed militias have consistently defined their actions of ethnic cleansing against the native population of the region as “jihad” against peoples perceived as insufficiently Islamic and Arabized. For example, as armed forces spokesman Mohamed Beshir Suleiman put it in August 2004, “The door of the jihad is still open and if it has been closed in the south it will be opened in Darfur.”

As Sadiq al-Mahdi, a leading opposition figure in Sudan, summed up: “The catastrophe that afflicted our country began with the takeover by a minority party that imposed an Arabic Islamic identity on a country of diverse religions and cultures, treating whoever did not agree with it as a renegade to be fought by jihad.”

And so it is today that activists in South Kordofan and Blue Nile point to the real solution required if Sudan is ever to move forward. In the words of Amar Amoun, a Nuban MP from South Kordofan, there must be a “democratic, secular Sudan where we all have rights.” Yet the international community at large seems unwilling to acknowledge the role of jihad theology and Arab supremacist attitudes behind Khartoum’s behavior.

In the meantime, where are the calls for a UN-mandated no-fly zone over South Kordofan and Blue Nile? Where are the demands for a NATO bombing campaign against Sudan’s armed forces? Answer: they do not exist.

Why? Because, unlike Gaddafi, Omar al-Bashir has not been abandoned by the Arab League, which gave him a red-carpet welcome at the group’s summit in Qatar in 2009; nor have members of the Gulf Cooperation Council, which is increasingly replacing the Arab League as an inter-Arab political body, thought it necessary to denounce the Sudanese president. Such is the racist hypocrisy of the Arab governments, which have similarly failed to condemn the horrific treatment of black migrant workers in Libya at the hands of militias that were fighting against Gaddafi.

Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi is a student at Brasenose College, Oxford University, and an intern at the Middle East Forum.

RSS

RSS

Sudan in Crisis | Middle East, Israel, Arab World, Southwest Asia, Maghreb http://t.co/PBJHjjME

Sudan in Crisis | Middle East, Israel, Arab World, Southwest Asia, Maghreb http://t.co/PBJHjjME