![]()

Colgate.edu | by Michael Sells

I

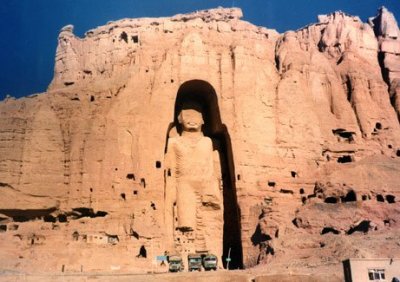

When the Taliban destroyed the ancient, massive Buddhist rock-wall sculptures (march 2001) a few months ago, a number of Muslims sent around petitions urging the world to see how dangerous the Taliban were. These monuments had survived the Mongols and other invaders, and had coexisted with centuries of Islamic civilization.

Those protesting the destruction were mocked (by some Muslims and non-Muslims alike) who argued that it was silly to protest the fate of statues when human beings were suffering. But the blasted Buddhas were a warning call as ominous as the Serb army’s deliberate campaign of cultural annihilation at the outset of its 1992 campaign in Bosnia that swiftly turned into genocide. Destroying symbols is not unrelated to neglecting or destroying human beings; indeed, it is an announcement of both the intention to carry out the latter project in as efficient a way as possible. But the wake-up call, as loud as it was, was not heeded in the U.S. by a public and press more concerned with tabloid scandal news on Monica Lewinsky, Denise Rich, or Gary Condit.

The current effort to differentiate “terrorists” from Muslims in the U.S. has been undermined by a naivete in the West about the power of images, while the Taliban and Bin Laden employ a sophisticated understanding of image and media to present themselves as representatives of Islam and to haunt and taunt the Western producers of such media.

When the Iranian militant hostage-takers, Saddam Hussein, or the Taliban invited the media in for staged photo-ops, they were taking control of the image of Islam in the Western world. They set us up. Images of Taliban students sitting above the written text of the Qur’an allegedly “studying the Qur’an” (when actually they are studying intense political indoctrination), or of Bin Laden surrounded by Arabic script and Islamic symbols, are shown repeatedly by the media, interspliced with pictures of the planes flying into the Towers or other horrors, along with the human suffering of the victims and their relatives and survivors.

Once that image-association is made, explanations that not all Muslims are terrorists are as effective lectures on dangers of cigarette smoking after someone has ingested thousands of images of smokers as Marlboro man, Sexy man, Sophisticated Woman, Liberated Woman, Thoughtful Man, Social Man, Powerful Woman. Advertisers spend billions of dollars finding the exact association that will work in an instant fly-by billboard flash that most people are hardly conscious of as they are driving, but which are clearly effective.

Once someone has seen the image association of mass-killer (Saddam, Bin Laden), Islamic symbol (written Qur’an, Muslims praying, sounds of the call to prayer) and atrocity (towers burning and collapsing, relatives of victims in anguish), it becomes extraordinarily difficult, however much that person tries, to hear and listen to the voices of the vast world of Islam beyond such associations.

An 8th grader question at a forum I was giving: “why can’t we find Bin Laden if he’s always on TV.” He had hit upon a core problem.

Bin Laden is a man living with the Taliban, who have banned all images (except for identity card photos), but who invite Western camera crews to make videos of them themselves smashing TV’s and tearing up video and audio cassette film, and to photograph them stomping on photographs. Then the Taliban and Bin Laden work to have these images of themselves (including of themselves smashing images) shown continually throughout the world (except in Afghanistan were television all image-media are banned).

One aspect of the Taliban’s ultra-iconoclasm has been Saudi-born Wahhabism — the fringe sect in Islam that has dominated self-representation of Islam recently through its massive funding and propaganda. Wahhabism takes its name from the fanatical reformer Muhammad ibn ‘abd al-Wahhab (1703-1787), who allied himself with the tribal warlords that eventually became the Saudi dynasty and whose descendants married into the Saudi clans. Through the wealth and power of that dynasty, Wahhabism has been able to project its vision of Islam around the world, both within the Islamic world and to the West, as a dominate representation of Islam.

Wahhabism abhors images as idols. It views almost all popular forms of Islam as idolatry and image-worship, and views images as a “pollution” from of non-believers into belief. In Saudi Arabia, all popular shrines have been systematically annihilated; Sufism and Sufi literature prohibited; even the tombs of the companions of the Prophet Muhammad have been leveled to make sure they would not be objects of veneration; hundreds of old buildings in Mecca and Medina have been razed and the sites excavated down to the bedrock in an attempt to remove any suspected shrines and any buried remains of popular saints. Wahhabi inspired “reconstruction” has turned the Mosque of the Two Qiblas into sterile palaces of extravagant banality. Wahhabism has special contempt for versions of Islam that show openness to other religions and other traditions.

Wahhabism is obsessed with purity and views non-Muslims (as well as non-Wahhabi Muslims) as a “pollution” not only of Mecca and Medina, but of the entire Saudi state. Osama bin Laden grew up with this ideology and turned in fury on the Saudi regime when it violated its own Wahhabist principles by allowing American soldiers to remain in the Kingdom after the Gulf War.

The extent and ruthlessness of Wahhabi projection of its power can be seen in Bosnia and Kosov where Saudi-financed groups have taken over control of towns and neighborhoods with promises of large financial aid, and then, before people have a chance to react, have dynamited or otherwise destroyed some of the few classic Islamic monuments of the 15-th-17th century that survived organized annihilation by Serb and Croat forces — a third, stealth, wave of “ethnic cleansing.” I’ve posted an article on this, with before and after pictures of the Wahhabi “renovation” (annihilation) of the interior of the Begova Mosque (16th century) in Sarajevo, the major Islamic monument that had been left intact in Bosnia-Herzegovina. These pictures explain, more than a thousand words, the aggressive strain of Wahhabism.

Muslims throughout the world have been faced with well-financed self-proclaimed representatives of true Islam, who have studied at the fundamentalist schools in the prestigious universities in Medina and Mecca, know their classical Arabic and the elements of Islamic law, and effectively silence the thousands of other versions of Islam. If this tragedy can lead to constructive change, one aspect of that change — already emerging — would be the empowerment of Muslims to take back their own version of Islam from Saudi and Gulf sponsored missionaries in their own communities, and to work to find alternatives in Pakistan to the Wahhabi-sponsored Madrasas which are the only education available for large number of Pakistanis.

But there is another aspect to the hyper-Wahhabism of the Taliban: general anger in traditional societies (including places like Cincinnati, I might add, and even those segments of New Yorker society protesting against certain art works in the Brooklyn Museum) over the pervasive and powerful influence of “decadent” Western advertising, films, music, and other forms of imaging.

Traditional cultures are being wrenchingly impacted by globalized Western culture, but none act with the fanaticism of the Taliban. And Wahhabism has spread throughout the Islamic world on the wings of Saudi oil and money, but few Wahhabis, even those who attack Sufi shrines, act with the extreme fanaticism of the Taliban. The two elements have linked and compounded one another: We have a modern-born sect, Wahhabism, that came to dominance by sitting on the major oil supply of the world combining with a post-modern or communications-age globalized war of icon vs iconoclasm.

II

Wahhabism was exported to the Taliban (who already held to a militant fundamentalism grown out of the Deoband movement in South Asia) through its Saudi sponsors. The Saudis funded the Taliban’s rise to power and sent them the crucial military help (organized by Prince Turki al-Faisal, the recently dismissed head of the Saudi intelligence service). Saudi millionaire Osama Bin Laden had become not only a major financial backer of the Taliban, but also the major theological advisor to Taliban leader Mulla Omar. Meanwhile, Mulla Omar has allegedly never been photographed — putting himself in the position of Muhammad, any image of whom is considered an offense (if images entail image-worship, then an image of Muhammad would substitute the prophet of God for God).

Wahhabism has succeeded not only because of the Gulf-financed extension of radical Wahhabi missions throughout the Islamic world, but also because the Wahhabi message strikes a particular nerve. Wahhabi iconoclasm appeals to those who feel invaded by images. Billboards (in Nordic taste) for swimsuits and lingerie (pictures that would raise protest in Cincinnati) hover over streets of people who have lived a lifetime with different notions of modesty. Lines of adolescent young men can be found throughout the traditional world, waiting to see U.S. produced movies, dubbed into Arabic, with names like “Lethal Weapon III: Extreme,” — films that are consumed insatiably in much of the non-industrialized world. This sense of image-invasion is compounded by bitterness over military invasion (as in the Gulf War and its horrific, still continuing aftermath), or in the West Bank (which for many in the region is what Waco would be for many rural American Christians, if it were an act repeated every day for decades — a constant, slow-motion, day by day invasion further and further into the remnants of Palestinian lands).

Osama bin Laden and those behind him understand symbols better than most. They set up the Trade Towers horror to outdo the disaster films that are part of the world of image that is produced by, and in turn controls, the Western world. They knew these fact-is-beyond-the-widest-fantasy images of horror would be repeated traumatically day by day. They and the Taliban have annihilated what they consider to be the poison of image in their own realm and turned it back — in the most calculated and deadly manner — on its producer. The fact that fundamentalists are products of modernity rather than atavistic throwbacks to the past has never been so starkly revealed.

None of this — Bin Laden, the Taliban, the modernist Wahhabist extremist Sheikhs in Saudi Arabia with their mansions, jets, and international banking connections — has anything whatsoever to do with a desire for the medieval past. Nor does the present, bombed out Afghanistan have anything to do with the medieval Afgan past that produced many of the scientists, artists, poets, architects, and other cultural worlds of classical Islam, of which Rumi (a contemporary celebrity in the West) was one particularly famous example among hundreds. Nor does contemporary stone-age Afghanistan have anything to do with the recent pre-war past, with its universities, religious pluralism, and vibrant intellectual life.

The same people who feel invaded by such images are themselves working to attain many of the products being sold. Fundamentalists in Islam (and in most of the world) are not back-to-the-past Amish type groups wishing to return to the days of horse and buggy and non-mechanized society. And the constant use of cliches like “medieval” to describe fundamentalists shows ignorance both of the richness, suppleness, and creative vigor of medieval Islamic society and ignorance of the narrowness of education of most fundamentalists, who frequently know more about modern engineering or computers than they do about their own tradition. Many of fundamentalism’s major ideologues and backers have studied in the West. They are fighting a battle not to destroy modernity, but to control it. The Wahhabis have embraced technology, but they use it in a manner that attempts to detach it from image-flow; an attempt that may ultimately fail, but which is now the norm.

Contemporary fundamentalists present themselves as returning to a pure, classical model of Islam, but they violently reject what little they know of the actual history and civilization of Islam. Their model of the past is one constructed out of their own ideologies, their own confrontation with social and political chaos, and their own determination to radically change the conditions under which they live. Their rhetoric appeals to the Qur’an, but is often structured according logics of the enlightment and post-enlightment thought they claim to reject.

When I think of the cultural pain I have in moving from Tunisian villages or even Damascus back to an image driven culture, in which each year the frames of movies and videos are speeded, as life becomes more a series of shorter interactions, I can only imaging the shock of those born in such villages and now pulled between the remains of traditional life and the increased power of globalized, image-driven, capitalist culture. This culture shock is deep and pervasive everywhere, but in the Islamic world it is combined with a long-standing and deep sense of grievance against Western and U.S. policy, intensifying the alienation.

In the West, the world of advertising and image is defended as “free speech.” Thus, images of smoking (to take one example) use image associations (tough, sexy, social, sophisticated, thoughtful) to implant an association so powerful it becomes relatively impervious to any counter-information, even the obvious fact that the product consumed will likely make the person into the very opposite of all the above). Efforts to ban such images completely are met by claims that to ban them would be to deprive citizens of the free flow of “information,” though the information is communicated by a billboard, subliminally glimpsed on a commuter road twice a working day for years, is a special kind of in-form-ation indeed. This is the world of freedom and free choice. But for the iconoclast, images enslave. We worship them. They offer no free choice. Freedom can be attained only when they are demolished.

The dominant force of advertising is sex, primarily hypersexualized images of women (though men are now, in the spirit of liberation, also taking their place as advertising sex objects — though usually paid much less and considered much more expendable than a classic female model). The virtual imprisonment of women by the Wahhabis in Saudi Arabia, and the actual imprisonment of women by the Taliban (they are under house arrest, not allowed to leave without their jailkeeper male relative, not allowed to study, to work outside, to have any public existence whatsoever) is often confused by Westerners with the issue of the veil. But it is more than that. Iranian women have had the veil imposed, then forbidden (by the first Shah), then imposed again, then discouraged (by the second Shah), then imposed again. But Iranian women make up a huge percentage of professionals in Iran — teachers, doctors, lawyers, engineers etc. — in some cases percentages exceeding that in Western nations like the U.S., whereas Afghan women have no role whatsoever.

There are many factors behind this (including customs among the rural Pushtuns), but none can explain this radical imposition of a state of imprisonment of women. For the Taliban or other radical iconoclast, the face of the woman is an image, thus an idol. It attracts irresistibly, thus enslaves. Dynamiting Buddhas and hiding away women in house arrest are part of the same iconoclastic war. And pushing the image back onto the Western societies that produce it (and — in the mind of hyper-radicalized Wahhabism — worship it) is to use the enemy against the enemy itself.

III

Our defense department was planning a trillion dollar, literal, hardware Star Wars program, only to be surprised by the image of a man sitting in a desert shepherd’s cloak, in a not-even-tent, in a place bombed back to before the stone age, appearing everywhere — an image repeated endlessly and coming from all directions. The U.S. military, financial, and technical empire was penetrated by those armed with box cutters and threatened by the viritual presence of this fanatic — as if by some superior alien culture out of the wildest dreams science fantasy films.

In Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1997), Jan Assmann presents the story of the proto-Monthotheist Pharoah Akhenaten. He probes the way in which radical monotheism and radical iconoclasm are linked in the roots of the Abrahamic tradition and raises troubling questions about how such elements of the traditions can be made compatible with an acceptance of the religious other. The same issue is raised now anew, in a manner that recalls the violences evoked by Assmann, but with the modern and post-modern worlds of icon added to the already combustible nature of the issue of monotheistic exclusivism. Even as those same issues were recalled, this time with an organized persecution of Muslims in the name of Christianity, during the “ethnic cleansings” in Bosnia.

Not all wahhabis are Wahhabis; that is, not all those who share the traits of formal Wahhabis see themselves in any conscious way as followers of Muhammad ibn ‘abd al-Wahhab. Yet this form of fundamentalism is identifiable and distinguishable from other forms, through the traits described above, and whether an ‘alim (learned person — loosely and poorly translated as “cleric”) who holds this same vision or not thinks of Ibn ‘abd al-Wahhab or even knows who ‘Abd al-Wahhab was, it is likely he has been influenced, directly or indirectly, by the Wahhabi-propaganda on “true Islam.” It should be emphasized that many Saudis are not Wahhabis and have been resisting the Wahhabi domination in the Gulf.

Still, almost since the Saudi dynasty consolidated its power over the Arabian peninsula under the rule of Ibn Saud, the West has supported it in exchange for secure access the oil reserves that are the physical energy foundation of Western economies — despite the fact that the dominate ideology of that regime is hostile to the image, the symbolic energy of adverstising-based capitalism and its main product.

Yet most ultraradical Wahhabis know that they cannot resist the images they reject. The impossibility of living up to the Wahhabi ideal explains in part the notorious hypocrisy of Saudi males who organize morals police beat men or women who show skin, and then go off to Europe and Asia to enjoy sex, alcohol, and pornography in areas of town that cater specifically to wealthy Saudi men.

The Muhammad Attas of the world live both extremes — a life of increasingly intense piety alternating with binges of Western decadence. There is no reason to be surprised at such a double life. The more the image is repressed, the more powerfully its power comes back. Their hatred is a self-hatred at the extreme nature of their betrayal of their extremist belief. Killing the other and the self at the same time is a perfect solution. It has nothing to do with any particular religion and reading the letter of Atta to see which Qur’an passages he quotes is interesting, but really peripheral to the larger problem.

But the icon wars that are now taking place do relate, I think,do relate to the radical iconoclasm within Abrahamic traditions. (An iconoclasm shared by us Quakers, who, back in the days of George Fox, used to be much more fierce that most of us Quakers are today, and truly scary to the rest of the world as they burst into Church services and angrily denounced the blasphemy of churches and images). Of course not all people in monotheistic traditions, or even most, or even a large minority, take the implications of iconoclasm to their extreme limit. But when Abraham smashed the images of his father or showed willingness to sacrifice his son, he may be interpreted by some as showing that one cannot be partially iconoclast. As President Bush said: “you are either on our side or theirs. You must make a choice.”

This issue is only one of several interlinked elements: the catastrophe of the Gulf War and its aftermath; the equally catastrophic failure of the Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement last year — a peace that would not deter the Bin Ladens in the short term (and would actually incite them further, if that is possible), but which will, in the long term, help drive a stake through their heart; to the difficulty of most non-Muslims in the West, even if they could get the media images out of their mind for a moment, to achieve a genuine sense of the Qur’an and Islamic civilization more widely. And this particular issue of the Taliban and image wars is itself is made of interlinked internal factors. But it is one part of the puzzle, and a part of the puzzle that leads to deeper questions about the iconoclastic and exclusive roots within monotheistic belief and the possibility of overcoming those roots.

![]()

Michael Anthony Sells is currently the John Henry Barrows Professor of Islamic History and Literature at the Divinity School of the University of Chicago.

RSS

RSS

[…] for Afghan’s cultural heritage, other beliefs or minorities. They destroyed for example two enormous ancient Buddhist sculptures in Bamiyan province. Temples and Hindu property were looted and burnt in Kabul, Kandahar and […]