![]()

By Crethi Plethi

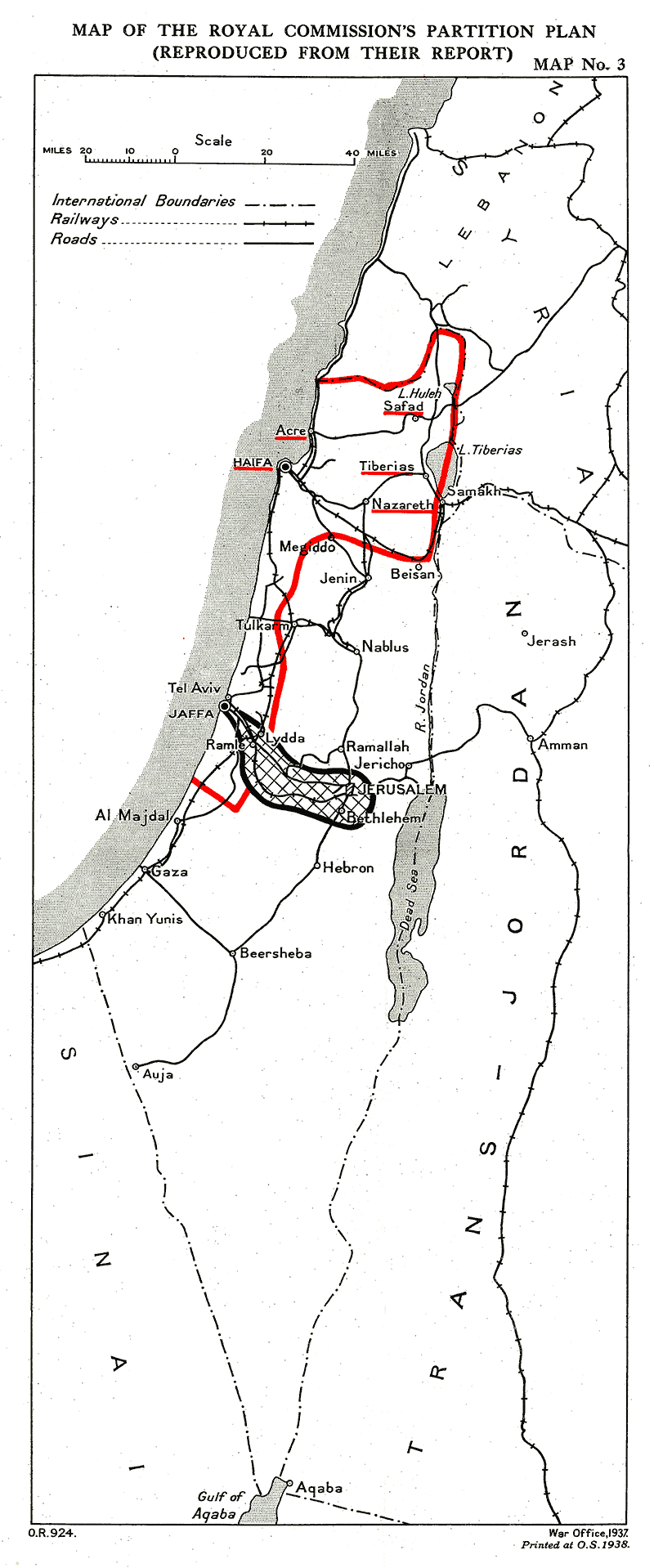

Map of the Peel Partition plan as proposed by the Peel Commission report, 1937. The area outlined with red lines was proposed as Jewish State, the shaded area was proposed as international territory (British Mandate) and the rest of Palestine was proposed as Arab State.

The Palestine Royal Commission was a British Royal Commission of inquiry led by Lord Robert Peel, hence known as the Peel Commission, and sent to British Mandatory Palestine in November of 1936 to investigate and determine the causes of the Arab-Jewish violence in Mandatory Palestine and propose an appropriate course of action. On July 7, 1937, after months of investigation, research and interviews with Jewish and Arab leaders, the Commission published its report stating that the Mandate had become unworkable because Arab and Jewish objectives in Mandatory Palestine were incompatible and, for the first time, recommended that Palestine be partitioned into three separate territories: an Arab state, a Jewish state, and a neutral territory containing the holy places.

The Jewish leadership accepted the Peel Partition recommendations as an opportunity and basis for more negotiation. The Arab leadership called a pan-Arab summit in Bloudan, Syria on 8 September 1937, known as The Bloudan Conference, in response to the Peel Partition recommendations. Hundreds of delegates from across the Arab world adopted several resolutions during the conference denouncing the Peel Commission recommendation to partition Palestine, rejecting the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine and affirming that Palestine was an integral part of the Arab world. The Arab delegates also voiced their support for the Arab revolt (1936–39) in Palestine against the British authorities and increased Jewish immigration in Palestine.

The British cabinet initially endorsed the Peel Partition recommendations, but requested more information. On February 1938, the Woodhead Commission (led by Sir John Woodhead) was appointed to examine the Peel Commission Report in detail and recommend an actual partition plan. The Woodhead Commission published their report on November 9, 1938. In their report, they examined three possible modifications of the Peel Commission proposal, which they called Plans A, B and C. The British government in 1938 believed that such partitioning would be infeasible and, as a consequence, stated that “the political, administrative and financial difficulties involved in the proposal to create independent Arab and Jewish States inside Palestine are so great that this solution of the problem is impracticable.” (Statement by His Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom, presented by the Secretary of State for the Colonies to Parliament by Command of His Majesty, November, 1938. Cmd. 5893.)

Read the text of the Peel Commission report below (source: League of Nations/UNISPAL). You can download this article in PDF here.

![]()

C.495.M.336.1937.VI.

Geneva, November 30th, 1937.

LEAGUE OF NATIONS

MANDATES

P A L E S T I N E

—

REPORT

of the

PALESTINE ROYAL COMMISSION

presented by the Secretary of State for the Colonies

to the United Kingdom Parliament

by Command of His Britannic Majesty

(July 1937)

Distributed at the request of the United Kingdom Government.

Series of League of Nations Publications

VI. A. MANDATES

1937. VI A. 5

OFFICIAL COMMUNIQUE IN 9/37

PALESTINE

Royal Commission

—

SUMMARY OF REPORT

SUMMARY OF THE REPORT OF THE PALESTINE ROYAL COMMISSION.

The Members of the Palestine Royal Commission were:-

Rt. Hon. EARL PEEL, G.C.S.I., G.B.E. (Chairman).

Rt. Hon. Sir HORACE RUMBOLD, Bart., G.C.B., G.C.M.G., M.V.O. (Vice-Chairman).

Sir LAURIE HAMMOND, K.C.S.I., C.B.E.

Sir MORRIS CARTER, C.B.E.

Sir HAROLD MORRIS, M.B.E., K.C.

Professor REGINALD COUPLAND, C.I.E.

Mr. J. M. MARTIN was Secretary.

—

The Commission was appointed in August, 1936, with the following terms of reference:-

To ascertain the underlying causes of the disturbances which broke out in Palestine in the middle of April; to enquire into the manner in which the Mandate for Palestine is being implemented in relation to the obligations of the Mandatory towards the Arabs and the Jews respectively; and to ascertain whether, upon a proper construction of the terms of the Mandate, either the Arabs or the Jews have any legitimate grievances on account of the way in which the Mandate has been or is being implemented; and if the Commission is satisfied that any such grievances are well-founded, to make recommendation for their removal and for the prevention of their recurrence.

The following is a summary of the Commission’s Report: –

SUMMARY

—

PART I: THE PROBLEM

Chapter I. – The Historical Background

A brief account of ancient Jewish times in Palestine, of the Arab conquest and occupation, of the dispersion of the Jews and the development of the Jewish Problem, and the growth and meaning of Zionism.

Chapter II. – The War and the Mandate

In order to obtain Arab support in the War, the British Government promised the Sherif of Mecca in 1915 that, in the event of an Allied victory, the greater part of the Arab provinces of the Turkish Empire would become independent. The Arabs understood that Palestine would be included in the sphere of independence.

In order to obtain the support of World Jewry, the British Government in 1917 issued the Balfour Declaration. The Jews understood that, if the experiment of establishing a Jewish National Home succeeded and a sufficient number of Jews went to Palestine, the National Home might develop in course of time into a Jewish State.

At the end of the War, the Mandate System was accepted by the Allied and Associated Powers as the vehicle for the execution of the policy of the Balfour Declaration, and, after a period of delay, the Mandate for Palestine was approved by the League of Nations and the United States. The Mandate itself is mainly concerned with specific obligations of equal weight–positive obligations as to the establishment of the National Home, negative obligations as to safeguarding the rights of the Arabs. The Mandate also involves the general obligation, implicit in every Mandate, to fulfil the primary purpose of the Mandate System as expressed in the first paragraph of Article 22 of the Covenant.

This means that the well-being and development” of the people concerned are the first charge on the Mandatory, and implies that they will in due course be enabled to stand by themselves.

The association of the policy of the Balfour Declaration with the Mandate System implied the belief that Arab hostility to the former would presently be overcome, owing to the economic advantages which Jewish immigration was expected to bring to Palestine as a whole.

Chapter III. – Palestine from 1920 to 1936

During the first years of the Civil Administration, which was set up in 1920, a beginning was made on the one hand with the provision of public services, which mainly affected the Arab majority of the population. and on the other hand with the establishment of the Jewish National Home. There were outbreaks of disorder in 1920 and 1921, but in 1925 it was thought that the prospects of ultimate harmony between the Arabs and the Jews seemed so favourable that the forces for maintaining order were substantially reduced.

These hopes proved unfounded because, although Palestine as a whole became more prosperous, the causes of the outbreaks of 1920 and 1921, namely, the demand of the Arabs for national independence and their antagonism to the National Home, remained unmodified and were indeed accentuated by the “external factors,” namely, the pressure of the Jews of Europe on Palestine and the development of Arab nationalism in neighbouring countries.

These same causes brought about the outbreaks of 1929 and 1933. By 1936 the external factors had been intensified by–

(1) the sufferings of the Jews in Germany and Poland, resulting in a great increase of Jewish immigration into Palestine; and

(2) the prospect of Syria and the Lebanon soon obtaining the same independence as Iraq and Saudi Arabia. Egypt was also on the eve of independence.

Chapter IV. – The Disturbances of 1936

These disturbances (which are briefly summarized) were similar in character to the four previous outbreaks, although more serious and prolonged. As in 1933, it was not only the Jews who were attacked, but the Palestine Government. A new feature was the part played by the Rulers of the neighbouring Arab States in bringing about the end of the strike.

The underlying causes of the disturbances of 1936 were–

(1) The desire of the Arabs for national independence;

(2) their hatred and fear of the establishment of the Jewish National Home.

These two causes were the same as those of all the previous outbreaks and have always been inextricably linked together. Of several subsidiary factors, the more important were–

(1) the advance of Arab nationalism outside Palestine;

(2) the increased immigration of Jews since 1933;

(3) the opportunity enjoyed by the Jews for influencing public opinion in Britain;

(4) Arab distrust in the sincerity of the British Government;

(5) Arab alarm at the continued Jewish purchase of land;

(6) the general uncertainty as to the ultimate intentions of the Mandatory Power.

Chapter V. – The Present Situation

The Jewish National Home is no longer an experiment. The growth of its population has been accompanied by political, social and economic developments along the lines laid down at the outset. The chief novelty is the urban and industrial development. The contrast between the modern democratic and primarily European character of the National Home and that of the Arab world around it is striking. The temper of the Home is strongly nationalist. There can be no question of fusion or assimilation between Jewish and Arab cultures. The National Home cannot be half-national.

Crown Colony government is not suitable for such a highly educated, democratic community as the National Home and fosters an unhealthy irresponsibility.

The National Home is bent on forcing the pace of its development, not only because of the desire of the Jews to escape from Europe, but because of anxiety as to the future in Palestine.

The Arab population shows a remarkable increase since 1920, and it has had some share in the increased prosperity of Palestine. Many Arab landowners have benefited from the sale of land and the profitable investment of the purchase money. The fellaheen are better off on the whole than they were in 1920. This Arab progress has been partly due to the import of Jewish capital into Palestine and other factors associated with the growth of the National Home. In particular, the Arabs have benefited from social services which could not have been provided on the existing scale without the revenue obtained from the Jews.

Such economic advantage, however, as the Arabs have gained from Jewish immigration will decrease if the political breach between the races continues to widen.

Arab nationalism is as intense a force as Jewish. The Arab leaders’ demand for national self-government and the shutting down of the Jewish National Home has remained unchanged since 1929. Like Jewish nationalism, Arab nationalism is stimulated by the educational system and by the growth of the Youth Movement. It has also been greatly encouraged by the recent Anglo-Egyptian and Franco-Syrian Treaties.

The gulf between the races is thus already wide and will continue to widen if the present Mandate is maintained.

The position of the Palestine Government between the two antagonistic communities is unenviable. There are two rival bodies — the Arab Higher Committee allied with the Supreme Moslem Council on the one hand, and the Jewish Agency allied with the Va’ad Leumi on the other — who make a stronger appeal to the natural loyalty of the Arab and the Jews than does the Government of Palestine. The sincere attempts of the Government to treat the two races impartially have not improved the relations between them. Nor has the policy of conciliating Arab opposition been successful. The events of last year proved that conciliation is useless.

The evidence submitted by the Arab and Jewish leaders respectively was directly conflicting and gave no hope of compromise.

The only solution of tile problem put forward by the Arab Higher Committee was the immediate establishment of all independent Arab Government, which would deal with the 400,000 Jews now in Palestine as it thought fit. To that it is replied that belief in British good faith would not be strengthened anywhere in the world if the National Home were now surrendered to Arab rule.

The Jewish Agency and the Va’ad Leumi asserted that the problem would be solved if the Mandate were firmly applied in full accordance with Jewish claims: thus there should be no new restriction on immigration nor anything to prevent the Jewish population becoming in course of time a majority in Palestine. To that it is replied that such a policy could only be maintained by force and that neither British public opinion nor that of World Jewry is likely to commit itself to the recurrent use of force unless it is convinced that there is no other means by which justice can be done.

—

PART II: THE OPERATION OF THE MANDATE

The Commission exhaustively considered what might be done in one field after another in execution of the Mandate to improve the prospects of peace. The results of this enquiry are embodied in Part II of the Report. The problems confronting the various branches of tile Mandatory Administration are described, and the grievances of the Arabs and Jews under each head discussed. The principal findings of the Commission are as follows:–

Chapter VI. – Administration

The Palestinian officers in the Government Service work well in normal times, but in times of trouble they are unreliable. There should be no hesitation in dispensing with the services of those whose loyalty or impartiality is uncertain.

As regards British officers, the cadre is too small to admit of a Civil Service for Palestine alone and the Administration must continue to draw on the Colonial Service, but the ordinary period of service in Palestine should be not less than seven years. Officers should be carefully selected and given a preliminary course of instruction.

The Commission recognise the difficulties of the British Administration, driven from the first to work at high pressure with no opportunity for calm reflection. There is over-centralization and insufficient liaison between Headquarters Departments and the District Administration.

The grievances and claims of the Arabs and Jews as regards the Courts cannot be reconciled and reflect the racial antagonism pervading the whole Administration. The difficulty of providing a judicial system suitable to the needs of the mixed peoples of Palestine is enhanced by the existence of three official languages, three weekly days of rest, three sets of official holidays and three systems of law. As regards Jewish suspicions as to the conduct of criminal prosecutions, the Commission point to the difficulties of the Legal Department in a land where perjury is common and evidence in many cases, particularly in times of crisis, unobtainable, and conclude that the animosity between the two races, particularly in times of crisis, has shown its influence to the detriment of the work of a British Senior Government Department. The appointment of a British Senior Government Advocate is recommended.

The Jaffa-Haifa road should be completed as speedily as possible.

Further expert enquiry is necessary before deciding whether a second deep-water port is required. It would be best to build such a port, if at all, at the junction of Jaffa and Tel Aviv, equally accessible from each.

There is no branch of the Administration with which the Jewish Agency does not concern itself but the Agency is not open to criticism on this ground. Article 4 of the Mandate entitles it to advise and co-operate with the Government in almost anything that may affect the interests of the Jewish population. It constitutes a kind of parallel government existing side by side with the Mandatory Government and its privileged position intensifies Arab antagonism.

The Arab Higher Committee was to a large extent responsible for maintaining and protecting the strike last year. The Mufti of Jerusalem as President must bear his due share of responsibility. It is unfortunate that since 1929 no action has been practicable to regulate the question of elections for the Supreme Moslem Council and the position of its President. The functions which the Mufti has collected in his person and his use of them have led to the development of an Arab imperium in imperio. He may be described as the head of a third parallel government. The Commission discuss a proposal for an enlarged Arab Agency, consisting of representatives of neighbouring Arab countries as well as of the Arabs in Palestine, to balance the Jewish Agency. If the present Mandate system continues some such scheme will have to be considered.

Chapter VII. – Public Security

Although expenditure on public security rose from £265,000 in 1923 to over £862,000 in 1935-36 (and £2,230,000 in 1936-37, the year of the disturbance) it is evident that the elementary duty of providing public security has not been discharged. Should disorders break out again of such a nature as to require the intervention of the Military, there should be no hesitation in enforcing martial law throughout the country under undivided military control. In such an event disarmament should be enforced and an effective frontier organisation established for stopping smuggling, illegal immigration and gun running. In the absence of disarmament the supernumerary police for the defence of Jewish Settlements should be continued as a disciplined force.

The collection of intelligence was unsatisfactory during the strike. The majority of Palestinian officers in the Criminal investigation Department are thoroughly devoted and loyal, but the junior ranks, like the majority of the District police, though useful in times of peace, are unreliable in time of trouble. It would be highly dangerous to expose the Arab police of Palestine to another strain of the same kind as that which they endured last summer.

In “mixed” areas British District Officers should be appointed.

Central and local police reserves are necessary. A large mobile mounted force is also essential, whether in the form of a Gendarmerie or by increasing the British Mounted Police.

After the 1929 disturbances, though 27 capital sentences were confirmed, only three murderers suffered the extreme penalty. In 1936 there were 260 reported cases of murder, 67 convictions and no death sentences. The prompt and adequate punishment of crime is a vital factor in the maintenance of law and order.

Collective fines totalling over £60,000 were imposed during the years 1929-36: only £18,000 has been collected up to date. If collective fines are to have a deterrent effect they should be limited to a sum that can be realized, and a body of punitive police should be quartered on the town or village until the fine has been paid.

The penalties provided by the Press ordinance and the action taken under it are insufficient. An Ordinance should be adopted providing for a cash deposit which can be confiscated and for imprisonment as well as payment of a fine; also, in case of a repetition of the offence, for forfeiture of the press.

Police barracks and married quarters are urgently necessary in certain towns.

The entire cost of the measures proposed could not be met from the revenues of Palestine. Grants-in-aid from His Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom would be required on a generous scale. The immediate effect of these measures would be to wider, the gulf that separates the Arab from the Jew, with repercussions spreading far beyond the borders of Palestine.

Chapter VIII. – Financial and Fiscal Questions

Until recent years the public finances allowed no great scope for development in the social services. The accumulation of a considerable surplus was a feature of the four years beginning 1932, and there were grounds for a conservative attitude towards this development. The conclusion that the existence of a large surplus reflects undue parsimony is not borne out by close analysis, since the entire surplus is found to be so heavily mortgaged that it is little more than a reasonable provision for existing commitments.

If the inward flow of capital, which is the most singular feature of the economy of Palestine, were to be arrested, there is no reason why the removal of exceptional advantages should result in penury, though there might be some reduction in the standard of living until the new economy was established. In the event of a prolonged period of economic stagnation the danger of an exodus of capital cannot be altogether excluded.

It is not possible in the absence of adequate statistics to measure the truth of the Arab complaint that industrial protection chiefly benefits the Jews and that its burdens are chiefly borne by the Arabs. It is hoped that the new Department of Statistics may soon enquire into the incidence of taxation and that new duties will be considered in relation to the whole burden of taxation and not merely as affecting the particular industry.

There is no question as to the need of increasing the export trade and finding markets for the ever increasing citrus output. After examining various possible expedients for overcoming the difficulties which result from the non-discrimination in tariff policy required by Article 18 of the Mandate, the Commission conclude that the provisions of Article 18 are out of date. Without an amendment of that Article Palestine must continue to suffer from the restrictions which hamper international trade, and negotiations should be opened without delay to put the trade of Palestine on a fairer basis.

Chapter IX. – The Land

A summary of land legislation enacted during the Civil Administration shows the efforts made to fulfil the Mandatory obligation in this matter. The Commission point to serious difficulties in connection with the legislation proposed by the Palestine Government for the protection of small owners. The Palestine Order in Council and, if necessary, the Mandate should be amended to permit of legislation empowering the High Commissioner to prohibit the transfer of land in any stated area to Jews, so that the obligation to safeguard the right and position of the Arabs may be carried out. Until survey and settlement are complete, the Commission would welcome the prohibition of the sale of isolated and comparatively small plots of land to Jews. They would prefer larger schemes for the rearrangement of proprietorship under Government supervision. They favour the proposal for the creation of special Public Utility Companies to undertake such development schemes subject to certain conditions.

An expert Committee should be appointed to draw up a Land Code.

Recommendations are made with a view to the expediting of settlement (the need for which is paramount) and to the improvement of settlement procedure.

The present system of Land Courts is contributory to delay. Until survey and settlement are complete there should be two or three Land Courts separate from the District Courts and each under a single British Judge.

Up till now the Arab cultivator has benefited on the whole both from the work of the British Administration and the presence of Jews in the country, but the greatest care must now be exercised to see that in the event of further sales of land by Arabs to Jews the rights of any Arab tenants or cultivators are preserved. Thus, alienation of land should only be allowed where it is possible to replace extensive by intensive cultivation. In the hill districts there can be no expectation of finding accommodation for any large increase in the rural population. At present, and for many years to come, the Mandatory Power should not attempt to facilitate the close settlement of the Jews in the hill districts generally.

The shortage of land is due less to purchase by Jews than to the increase in the Arab population. The Arab claims that the Jews have obtained too large a proportion of good land cannot be maintained. Much of the land now carrying orange groves was sand dunes or swamps and uncultivated when it was bought.

Legislation vesting surface water in the High Commissioner is essential. An increase in staff and equipment for exploratory investigations with a view to increasing irrigation is recommended. The scheme for the development of the Huleh district is commended.

The Commission fully realize the desirability of afforestation on a large scale of a long term forest policy, but, having regard to their conclusion as to the scarcity of land in the hills for the agricultural population, they cannot recommend a policy involving expropriation of cultivators on a large scale until other cultivable land or suitable employment on the land can be found for them. In the aggregate, however, a large amount of land is fit for afforestation but not for cultivation, and the Commission endorse a policy of afforestation of steep hillsides to prevent erosion the prevention of grazing on land fit for afforestation, and, where practicable, the establishment of village forests for the benefit of neighbouring cultivators.

Chapter X. – Immigration

The problem of immigration has been aggravated by three factors:–

(1) the drastic restrictions imposed on immigration in the United States,

(2) the advent of the National Socialist Government in Germany, and

(3) the increasing economic pressure on the Jews in Poland.

The continuous impact of a highly intelligent and enterprising race backed by large financial resources on a comparatively poor, indigenous community, on a different cultural level, may produce in time serious reactions. The principle of economic absorptive capacity, meaning that considerations of economic capacity and these alone should determine immigration, is at present inadequate and ignores factors in the situation which wise statesmanship cannot disregard. Political, social and psychological factors should be taken into account. His Majesty’s Government should lay down a political high level of Jewish immigration. This high level should be fixed for the next five years at 12,000 per annum. The High Commissioner should be given discretion to admit immigrants up to this maximum figure, but subject always to the economic absorptive capacity of the country.

Among other alterations in the immigration regulations the Commission recommend that the Administration should have direct control over the immigrants coming in under Category A(i) (persons with £1,000 capital), and any person who desires to enter Palestine under this category should convince the Immigration authority not only that he is in possession of £1,000, but also that there is room in Palestine for additional members in the profession, trade or business which he proposes to pursue.

The definition of dependency should be revised so as to fall under two heads, (1) near relatives who, dependency being presumed, would have a right to come in, and (2) other relatives, in respect of whom the Immigration authority would have to be satisfied that they can be maintained by the immigrant or permanent resident concerned, as long as they remain dependent for maintenance.

The final allocation of immigration certificates as determined by the Jewish Agency should be submitted by the High Commissioner for approval.

Greater use should be made of the machinery of the District Administration in making enquiries in connection with the preparation of the half-yearly Labour Schedules. The housing situation is an economic consideration to which greater regard should be given when considering absorptive capacity.

In so far as immigration has been the major factor in bringing the Jewish National Home to its present stage of development, the Mandatory has fully implemented this obligation to facilitate the establishment of a National Home for the Jewish people in Palestine, as in evidenced by the existence of a Jewish population of 400,000 persons. But this does not mean that the National Rome should be crystallized at its present size. The Commission cannot accept the view that the Mandatory, facilitated the establishment of a National Home, would be justified in shutting its doors. Its economic life depends to a large extent on further immigration and a large amount of capital has been invested in it on the assumption that immigration would continue.

Restrictions on Jewish immigration will not solve the Palestine problem. The National Home seems already too big to the Arabs and, whatever its size, it bars the to their attainment of national independence.

Chapter XI. – Trans-Jordan

The articles of the Mandate concerning the National Home do not apply to Trans-Jordan and the possibility of enlarging the National Home by Jewish immigration into Trans-Jordan rests on the assumption of concord between Arabs and Jews. Arab antagonism to Jewish immigration is at least as bitter in Trans-Jordan as it is in Palestine. The Government of Trans-Jordan would refuse to encourage Jewish immigration in the teeth of popular resistance.

Chapter XII. – Health

The Jewish grievances are summed up as complaints that not enough money has been spent, by the Mandatory Government to assist the medical services established by the Jews from their own resources. What is given to one service must be taken from another, and it is not always remembered that Palestine, despite the economic development of the National Home is still a relatively poor country. The whole question illustrates the difficulty of providing services in one State for two distinct communities with two very different standards of living.

Chapter XIII. – Public Works and Services

If it be assumed that the distribution of posts as between the two races should be proportional to the size of their respective populations, the Government have fairly maintained this proportion in the Civil Service generally, although the rapid expansion of the Jewish community has made this extremely difficult.

In Palestine, where there are different rates of pay for Arab and Jewish unskilled labourers, and also frequent fluctuations in wage rates, it is practically impossible to maintain employment on public works on any fixed proportion between the races.

The Commission make no recommendation with regard to the employment of Jews and non-Jews in Government Departments and on public works and services. They refer to the difficulties created by the antagonism between the two races, the differences in their standard of living and rates of wages and the additional complication of three different Holy Days, and state that they are satisfied that the Government have taken a broad view in dealing with the situation and that there is no foundation for the suggestion that the Government attitude towards the employment of Jews is unsympathetic.

Chapter XIV. – The Christians

The religious stake of the Christians in the Holy Places is just as great as that of the Jews or Moslems. The Christians of the world cannot be indifferent to the justice and well-being of their co-religionists in the Holy Land.

A memorandum setting out the grievances of the Arab Orthodox Community and complaining of the laissez-faire attitude of the Government was received too late for examination in detail, but it is pointed out that the Financial Commission appointed under the Orthodox Patriarchate Ordinance of 1928 has carried out an effective reform of the Patriarchate’s finances and that the reorganization of the internal affairs of the Patriarchate, including the establishment of a Mixed Council, has been discussed between the Government, the Patriarchate and the Laity and is at present under consideration by the Government.

The Commission refer to the question of Sunday work by Christian officials resulting from the strict observance of the Jewish Sabbath, and are disposed to agree with the view that the existing state of affairs throws too much work on Christians officials and impairs the spiritual influence of the Christian Church.

In political matters the Christian Arabs have thrown in their lot with their Moslem brethren.

Chapter XV. – Nationality Law and Acquisition of Palestinian Citizenship

As regards the grievances of the Arabs (stated to number about 40,000) who left Palestine before the War intending eventually to return but have been unable to obtain Palestinian citizenship, the Commission suggest that at least those who are able to establish all an unbroken personal connection with Palestine and who are prepared to give a definite formal assurance of their intention to return, should be admitted to Palestinian citizenship.

As regards Jews, the existing legislation implements the obligation of the Mandate on this subject. The Jews have not availed themselves readily of the opportunity afforded them of becoming Palestinian citizens, and this is accounted for by the fact that their chief interest is in the Jewish Community itself. Allegiance to Palestine and to the Government are minor considerations to many of them.

The Commission do not agree with those who criticise the restriction of the municipal franchise to Palestinian citizens. It is most desirable that all persons who intend to reside permanently in the country should become Palestinian citizens, and this qualification for voting is a direct inducement, to them to do so.

Chapter XVI. – Education

It seems unfortunate that the Administration has been unable to do more for education. It is not only the intrinsic value of education that should be considered. Any efforts to raise the material standards of life among the fellaheen can only be successful if they have received sufficient mental training to profit from technical instruction. Considering, the inadequacy of the existing provision for Arab education, the Administration should regard its claims on the revenue as second in importance only to those of public security.

Worse than the insufficiency of Arab schools, however is the nationalist character of the education provided in the schools of both communities and for that the Commission can see no remedy at all. The ideal system of education would be a single bi-national system for both races. But that is virtually impossible under the Mandate, which prescribes the right of each community to maintain its own schools for the education of its own members in its own language.” The existing Arab and Jewish school systems are definitely widening and will continue to widen the gulf between the two races.

Wherever practicable, e.g. in new technical or trade schools, mixed education should be promoted.

As regards the Jews’ claim for a larger grant for their system of education, the Commission consider that, until much more has been spent on the development of Arab education, so as to place it on a level with that of the Jews, it is unjustifiable to increase the grant to the latter, however desirable it might be in other circumstances. The extent to which the Jews have taxed themselves for education is one of the best features of the National Home; and such “self-help” deserves all support; but it should not be given by altering the present proportion between the grant to the Jews and the amount spent on the Arabs; it should result from an increase in the total expenditure on education.

The contrast between the Arab and Jewish systems of education is most striking at the top. The Jews have a university of high quality. The Arabs have none and the young intelligenzia of the country are unable to complete their education without the cost and inconvenience of going abroad. In any further discussion of the project of a British University in the Near East the possibility should be carefully considered of locating it in the neighbourhood of Jerusalem or Haifa.

Chapter XVII. – Local Government

The present system of rural self-government (through local Councils) falls short (1) in a lack of flexibility, (2) in undue centralization. An attempt should be made to strengthen those few local councils which still exist in the Arab rural areas, but the Commission do not favour an attempt at present to revivify councils which have broken down or to create new ones unless there is a genuine demand for them. There can be little really effective extension of village self-government until the provision of primary education has had more time to take effect.

The deficiencies of the present system of municipal government are (1) a lack of initiative on the part of the more backward municipalities, and (2) the limitations set to initiative on the part of the more progressive municipalities by an Ordinance which subjects them all to the same measure of Government control and centralized administration. The limitation of power and responsibility largely accounts for the lack of interest shown by the townspeople in most municipal councils.

Tel Aviv has unique problems of its own caused by its phenomenal growth during the last five years. The objectives which the people of Tel Aviv have set before them in the way of social services are in themselves admirable, and the ratepayers have shown a commendable readiness to bear high rates for their realization. The town has been faced with, and to a considerable extent surmounted, exceptional difficulties without seriously impairing its financial position.

The more important local councils and all the municipalities should be reclassified by means of a new Ordinance into groups according to their respective size and importance. The degree of power and independence could then be varied to suit each class. For the first class of municipality the powers provided under the existing Ordinance are inadequate and should be extended.

The services of an expert authority on local government should be obtained to assist in drafting the new Ordinance and in improving and co-ordinating the relations between Government and the municipalities, particularly in the larger towns, with special reference to the need of removing the causes of the present delay in approving municipal budgets.

The need of Tel Aviv for a substantial loan should be promptly and sympathetically reconsidered.

The normal constitutional relationship between the central and local authorities is impossible in Palestine.

Chapter XVIII. – Self-governing Institutions

Such hopes as may have been entertained in 1922 of any quick advance towards self-government have become less tenable. The bar to it–Arab antagonism to the National Home–so far from weakening, has grown stronger.

The Jewish leaders might acquiesce in the establishment of a Legislative Council on the basis of parity, but the Commission are convinced that parity is not a practicable solution of the problem. It is difficult to believe that so artificial a device would operate effectively or last long, and in any case the Arab leaders would not accept it.

The Commission do not recommend that any attempt be made to revive the proposal of a Legislative Council, but since it is desirable that the Government should have some regular and effective means of sounding public opinion on its policy, the Commission would welcome an enlargement of the Advisory Council by the addition of Unofficial Members, who might be in a majority and might be elected, who could make representations by way of resolution, but who would not be empowered to pass or reject the budget or other legislative measures. Again, the Arabs are unlikely to accept such a proposal.

The Arabs of Palestine, it has been admitted, are as fit to govern themselves as the Arabs of Iraq or Syria. The Jews of Palestine are as fit to govern themselves as any organized and educated community in Europe. Yet, associated as they are under the Mandate, self-government is impracticable for both peoples. The Mandate cannot be fully implemented nor can it honourably terminate in the independence of an undivided Palestine unless the conflict between Arab and Jew can be composed.

Chapter XIX. – Conclusion and Recommendations

The Commission recapitulate the conclusions set out in this part of the Report, and summarize the Arab and Jewish grievances and their own recommendations for the removal of such as are legitimate. They add, however, that these are not the recommendations which their terms of reference require. They will not, that is to say, remove the grievances nor prevent their recurrence. They are the best palliatives the Commission can devise for the disease from which Palestine is suffering, but they are only palliatives. They cannot cure the trouble. The disease is so deep-rooted that in the Commissioners’ firm conviction the only hope of a cure lies in a surgical operation.

—

PART III: THE POSSIBILITY OF A LASTING SETTLEMENT

Chapter XX. – The Force of Circumstances

The problem of Palestine is briefly restated.

Under the stress of the World War the British Government made promises to Arabs and Jews in order to obtain their support. On the strength of those promises both parties formed certain expectations.

The application to Palestine of the Mandate System in general and of the specific Mandate in particular implies the belief that the obligations thus undertaken towards the Arabs and the Jews respectively would prove in course of time to be mutually compatible owing to the conciliatory effect on the Palestinian Arabs of the material prosperity which Jewish immigration would bring in Palestine as a whole. That belief has not been justified, and there seems to be no hope of its being justified in the future.

But the British people cannot on that account repudiate their obligations, and, apart from obligations, the existing circumstances in Palestine would still require the most strenuous efforts on the part of the Government which is responsible for the welfare of the country.

The existing circumstances are summarized as follows.

An irrepressible conflict has arisen between two national communities within the narrow bounds of one small country. There is no common ground between them. Their national aspirations are incompatible. The Arabs desire to revive the traditions of the Arab golden age. The Jews desire to show what they can achieve when restored to the land in which the Jewish nation was born. Neither of the two national ideals permits of combination in the service of a single State.

The conflict has grown steadily more bitter since 1920 and the process will continue. Conditions inside Palestine especially the systems of education, are strengthening the national sentiment of the two peoples. The bigger and more prosperous they grow the greater will be their political ambitions, and the conflict is aggravated by the uncertainty of the future. “Who in the end will govern Palestine?” it is asked. Meanwhile, the external factors will continue to operate with increasing force. On the one hand in less than three years’ time Syria and the Lebanon will attain their national sovereignty, and the claim of the Palestinian Arabs to share in the freedom of all Asiatic Arabia will thus be fortified. On the other hand the hardships and anxieties of the Jews in Europe are not likely to grow less and the appeal to the good faith and humanity of the British people will lose none of its force.

Meanwhile, the Government of Palestine, which is at present an unsuitable form for governing educated Arabs and democratic Jews, cannot develop into a system of self-government as it has elsewhere, because there is no such system which could ensure justice both to the Arabs and to the Jews. Government therefore remains unrepresentative and unable to dispel the conflicting grievances of the two dissatisfied and irresponsible communities it governs.

In these circumstances peace can only be maintained in Palestine under the Mandate by repression. This means the maintenance of security services at so high a cost that the services directed to “the well-being and development” of the population cannot be expanded and may even have to be curtailed. The moral objections to repression are self-evident. Nor need the undesirable reactions of it on opinion outside Palestine be emphasized. Moreover, repression will not solve the problem. It will exacerbate the quarrel. It will not help towards the establishment of a single self-governing Palestine. It is not easy to pursue the dark path of repression without seeing daylight at the end of it.

The British people will not flinch from the task of continuing to govern Palestine under the Mandate if they are in honour bound to do so, but they would be justified in asking if there is no other way in which their duty can be done.

Nor would Britain wish to repudiate her obligations. The trouble is that they have proved irreconcilable, and this conflict is the more unfortunate because each of the obligations taken separately accords with British sentiment and British interest. The development of self-government in the Arab world on the one hand is in accordance with British principles, and British public opinion is wholly sympathetic with Arab aspirations towards a new age of unity and prosperity in the Arab world. British interest similarly has always been bound up with the peace of the Middle East and British statesmanship can show an almost unbroken record of friendship with the Arabs. There is a strong British tradition, on the other hand, of friendship with the Jewish people, and it is in the British interest to retain as far as may be the confidence of the Jewish people.

The continuance of the present system means the gradual alienation of two peoples who are traditionally the friends of Britain.

The problem cannot be solved by giving either the Arabs or the Jews all they want. The answer to the question which of them in the end will govern Palestine must be Neither. No fair-minded statesman can think it right either that 400,000 Jews, whose entry into Palestine has been facilitated by he British Government and approved by the League of Nations, should be handed over to Arab rule, or that, if the Jews should become a majority, a million Arabs should be handed over to their rule. But while neither race can fairly rule all Palestine, each race might justly rule part of it.

The idea of Partition has doubtless been thought of before as a solution of the problem, but it has probably been discarded as being impracticable. The difficulties are certainly very great, but when they are closely examined they do not seem so insuperable as the difficulties inherent in the continuance of the Mandate or in any other alternative arrangement. Partition offers a chance of ultimate peace. No other plan does.

Chapter XXI. – Cantonisation

The political division of Palestine could be effected in a less thorough manner than by Partition. It could be divided like Federal States into provinces and cantons, which would be self-governing in such matters as immigration and land sales as well as social services. The Mandatory Government would remain as a central or federal government controlling such matters as foreign relations, defence, customs and the like.

Cantonisation is attractive at first sight because it seems to solve the three major problems of land, immigration and self-government, but there are obvious weaknesses in it. First, the working of federal systems depends on sufficient community of interest or tradition to maintain harmony between the Central Government and the cantons. In Palestine both Arabs and Jews would regard the Central Government as an alien and interfering body. Secondly, the financial relations between the Central Government and the cantons would revive the existing quarrel between Arabs and Jews as to the distribution of a surplus of federal revenue or as to the contributions of the cantons towards a federal deficit. Unrestricted Jewish immigration into the Jewish canton might lead to a demand for the expansion of federal services at the expense of the Arab canton. Thirdly, the costly task of maintaining law and order would still rest mainly on the Central Government. Fourthly, Cantonisation like Partition cannot avoid leaving a minority of each race in the area controlled by the other. The solution of this problem requires such bold measures as can only be contemplated if there is a prospect of final peace. Partition opens up such a prospect. Cantonisation does not. Lastly, Cantonisation does not settle the question of national self-government. Neither the Arabs nor the Jews would feel their political aspirations were satisfied with purely cantonal self-government.

Cantonisation, in sum, presents most, if not all, of the difficulties presented by Partition without Partition’s one supreme advantage–the possibilities it offers of eventual peace.

Chapter XXII. – A Plan of Partition

While the Commission would not be expected to embark on the further protracted inquiry which would be needed for working out a scheme of Partition in full detail, it would be idle to put forward the principle of Partition and not to give it any concrete shape. Clearly it must be shown that an actual plan can be devised which meets the main requirements of the case.

1. A Treaty System

The Mandate for Palestine should terminate and be replaced by a Treaty System in accordance with the precedent set in Iraq and Syria.

A new Mandate for the Holy Places should be instituted to fulfil the purposes defined in Section 2 below.

Treaties of alliance should be negotiated by the Mandatory with the Government of Trans-Jordan and representatives of the Arabs of Palestine on the one hand and with the Zionist Organisation on the other. These Treaties would declare that, within as short a period as may be convenient, two sovereign independent States would be established–the one an Arab State consisting of Trans-Jordan united with that part of Palestine which lies to the cast and south of a frontier such as we suggest in Section 3 below; the other a Jewish State consisting of that part of Palestine which lies to the north and west of that frontier.

The Mandatory would undertake to support any requests for admission to the League of Nations which the Governments of the Arab and the Jewish States might make.

The Treaties would include strict guarantees for the protection of minorities in each State, and the financial and other provisions to which reference will be made in subsequent Sections.

Military conventions would be attached to the Treaties, dealing with the maintenance of naval, military and air forces, the upkeep and use of ports, roads and railways, the security of the oil pipe line and so forth.

2. The Holy Places

The Partition of Palestine is subject to the overriding necessity of keeping the sanctity of Jerusalem and Bethlehem inviolate and of ensuring free and safe access to them for all the world. That, in the fullest sense of the mandatory phrase, is “a sacred trust of civilization”–a trust on behalf not merely of the peoples of Palestine but of multitudes in other lands to whom those places, one or both, are Holy Places.

A new Mandate, therefore, should be framed with the execution of this trust as its primary purpose. An enclave should be demarcated extending from a point north of Jerusalem to a point south of Bethlehem, and access to the sea should be provided by a corridor extending to the north of the main road and to the south of the railway, including the towns Lydda and Ramle, and terminating at Jaffa.

The protection of the Holy Places is a permanent trust, unique in its character and purpose, and not contemplated by Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations. In order to avoid misunderstanding, it might frankly be stated that this trust will only terminate if and when the League of Nations and the United States desire it to do so, and that, while it would be the trustee’s duty to promote the well-being and development of the local population concerned, it is not intended that in course of time they should stand by themselves as a wholly self-governing community.

Guarantees as to the rights of the Holy Places and free access thereto (as provided in Article 13 of the existing Mandate), as to transit across the mandated area, and as to non-discrimination in fiscal, economic and other matters should be maintained in accordance with the principles of the Mandate System. But the policy of the Balfour Declaration would not apply; and no question would arise of balancing Arab against Jewish claims or vice versa. All the inhabitants of the territory would stand on an equal footing. The only official language” would be that of the Mandatory Administration. Good and just government without regard for sectional interests would be its basic principle.

It would accord with Christian sentiment in the world at large if Nazareth and the Sea of Galilee (Lake Tiberias) were also covered by this Mandate. The Mandatory should be entrusted with the administration of Nazareth and with full powers to safeguard the sanctity of the waters and shores of Lake Tiberias.

The Mandatory should similarly be charged with the protection of religious endowments and of such buildings, monuments and places in the Arab and Jewish States as are sacred to the Jews and the Arabs respectively.

For the upkeep of the Mandatory Government, a certain revenue should be obtainable, especially from the large and growing urban population in its charge, both by way of customs duties and by direct taxation; but it might prove insufficient for the normal cost of the administration. In that event, it is suggested that, in all the circumstances, Parliament would be willing to vote the money needed to make good the deficit.

3. The Frontier

The natural principle for the Partition of Palestine is to separate land and settled from the areas in which the Jews have acquired land and settled from those which are who are wholly or mainly occupied by Arabs. This offers a fair and practicable basis for Partition, provided that in accordance with the spirit of British obligations, (1) a reasonable allowance is made within the boundaries of the Jewish State for the growth of population and colonization, and (2) reasonable compensation is given to the Arab State for the loss of land and revenue.

Any proposal for Partition would be futile if it gave no indication, however rough, as to how the most vital question in the whole matter might be determined, i.e., the frontier. As a solution of the problem, which seems both practicable and just, a rough line is proposed below. A Frontier Commission should be appointed to demarcate the precise frontier.

Starting from Ras an Naqura, it follows the existing northern and eastern frontier of Palestine to Lake Tiberias and crosses the Lake to the outflow of the River Jordan, whence it continues down the river to a point a little north of Beisan. It then cuts across the Beisan Plain and runs along the southern edge of the Valley of Jezreel and across the Plain of Esdraelon to a point near Megiddo, whence it crosses the Carmel ridge in the neighbourhood of the Megiddo road. Having thus reached the Maritime Plain, the line runs southwards down its eastern edge, curving west to avoid Tulkarm, until it reaches the Jerusalem-Jaffa corridor near Lydda. South of the Corridor it continues down the edge of the Plain to a point about 10 miles south of Rehovot, when it turns west to the sea.

The observations and recommendations are made with regard to the proposed frontier and to questions arising from it:–

- No frontier can be drawn which separates all Arabs and Arab-owned land from all Jews and Jewish-owned land.

- The Jews have purchased substantial blocks of land in the Gaza Plain and near Beersheba and obtained options for the purchase of other blocks in this area. The proposed frontier would prevent the utilization of those lands for the southward expansion of the Jewish National Home. On the other hand, the Jewish lands in Galilee, and in particular the Huleh basin (which offers a notable opportunity for development and colonization), would be in the Jewish Area.

- The proposed frontier necessitates the inclusion in the Jewish Area of the Galilee highlands between Safad and the Plain of Acre. This is the part of Palestine in which the Jews have retained a foothold almost if not entirely without a break from the beginning of the Diaspora to the present day, and the sentiment of all Jewry is deeply attached to the “holy cities” of Safad and Tiberias. Until quite recently, moreover the Jews in Galilee have lived on friendly terms with their Arab neighbours; and throughout the series of disturbances the fellaheen of Galilee have shown themselves less amenable to political incitement than those of Samaria and Judaea where the centres of Arab nationalism are located. At the “mixed” towns of Tiberias, Safad, Haifa, and Acre there have been varying degrees of friction since the “disturbances” of last year. It would greatly promote the successful operation of Partition in its early stages, and in particular help to ensure the execution of the Treaty guarantees for the protection of minorities, if those four towns were kept for a period under Mandatory administration.

- Jaffa is an essentially Arab town and should form part of the Arab State. The question of its communication with the latter presents no difficulty, since transit through the Jaffa-Jerusalem Corridor would be open to all. The Corridor, on the other hand, requires its own access to the sea, and for this purpose a narrow belt of land should be acquired and cleared on the north and south sides of the town.

- While the Mediterranean would be accessible to the Arab State at Jaffa and at Gaza, in the interests of Arab trade and industry the Arab State should also have access for commercial purposes to Haifa, the only existing deep-water port on the coast. The Jewish Treaty should therefore provide for the free transit of goods in bond between the Arab State and Haifa.

The Arab Treaty, similarly, should provide for the free transit of goods in bond over the railway between the Jewish State and the Egyptian frontier.

The same principle applies to the question of access for commercial purposes to the Red Sea. The use of that exit to the East might prove in course of time of great advantage to both Arab and Jewish trade and industry, and, having regard to those possibilities, an enclave on the north-west coast of the Gulf of Aqaba should be retained under Mandatory administration, and the Arab Treaty should provide for the free transit of goods between the Jewish State and this enclave.

The Treaties should provide for similar facilities for the transit of goods between the Mandated Area and Haifa, the frontier and the Gulf of Aqaba.

4. Inter-State Subvention

The Jews contribute more per capita to the revenues of Palestine than the Arabs, and the Government has thereby been enabled to maintain public services for the Arabs at a higher level than would otherwise have been possible. Partition would mean, on the one hand, that the Arab Area would no longer profit from the taxable capacity of the Jewish Area. On the other hand, (1) the Jews would acquire a new right of sovereignty in the Jewish Area; (2) that Area, as we have defined it, would be larger than the existing area of Jewish land and settlement; (3) the Jews would be freed from their present liability for helping to promote the welfare of Arabs outside that Area. It is suggested, therefore, that the Jewish State should pay a subvention to the Arab State when Partition comes into effect. There have been recent precedents for equitable financial arrangements of this kind in those connected with the separation of Sind from Bombay and of Burma from the Indian Empire, and in accordance with those precedents a Finance Commission should be appointed to consider and report as to what the amount of the subvention should be.

The Finance Commission should also, consider and report on the proportion in which the Public Debt of Palestine, which now amounts to about £4,500,000, should be divided between the Arab and the Jewish States, and other financial questions. The Commission should also deal with telegraph and telephone systems in the event of Partition.

5. British Subvention

The Inter-State Subvention would adjust the financial balance in Palestine; but the plan involves the inclusion of Trans-Jordan in the Arab State. The taxable capacity of Trans-Jordan is very low and its revenues have never sufficed to meet the cost of its administration. From 1921 to the present day it has received grants-in-aid from the United Kingdom, which have amounted to a total sum of £1,253,000 or an average of about £78,000 a year. Grants have also been made towards the cost of the Trans-Jordan Frontier Force, and loans to the amount of £60, 000 have been provided for earthquake-relief and the distribution of seed.

The Mandate for Trans-Jordan ought not to be relinquished without securing, as far as possible, that the standard of administration should not fall too low through lack of funds to maintain it; and in this matter the British people might fairly be asked to do their part in facilitating a settlement. The continuance of the present Mandate would almost inevitably involve a recurrent and increasing charge on the British Treasury. If peace can be promoted by Partition, money spent on helping to bring it about and making it more effective for its purpose would surely be well spent. And apart from any such considerations the British people would, it is believed, agree to a capital payment in lieu of their present annual liability with a view to honouring their obligations and making peace in Palestine.

In the event of the Treaty system coming into force, Parliament should be asked to make a grant of £2,000,000 to the Arab State.

6. Tariffs and Ports

The Arab and Jewish States, being sovereign independent States, would determine their own tariffs. Subject to the terms of the Mandate, the same would apply to the Mandatory Government.

The tariff-policies of the Arab and Jewish States are likely to conflict, and it would greatly ease the position and promote the interests of both the Arab and Jewish States if they could agree to impose identical customs-duties on as many articles as possible, and if the Mandatory Government, likewise, could assimilate its customs-duties as far as might be with those of one or both of the two States.

It should be an essential part of the proposed Treaty System that a commercial convention should be concluded with a view to establishing a common tariff over the widest possible range of imported articles and to facilitating the freest possible interchange of goods between the three territories concerned.

7. Nationality

All persons domiciled in the Mandated Area (including Haifa, Acre, Tiberias, Safad and the enclave on the Gulf of Aqaba, as long as they remain under Mandatory administration) who now possess the status of British protected persons would retain it; but apart from this all Palestinians would become the nationals of the States in which they are domiciled.

8. Civil Services

It seems probable that, in the event of Partition, the services of the Arab and Jewish officials in the pre-existing Mandatory Administration would to a large extent be required by the Governments of the Arab and Jewish States respectively, whereas the number of British officials would be substantially reduced. The rights of all of them, including rights to pensions or gratuities, must be fully honoured in accordance with Article 28 of the existing Mandate. This matter should be dealt with by the Finance Commission.

9. Industrial Concessions

In the event of Partition agreements entered into by the Government of Palestine for the development and security of industries (e.g., the agreement with the Palestine Potash Company) should be taken over and carried out by the Governments of the Arab and Jewish States. Guarantees to that effect should be given in the Treaties. The security of the Electric Power Station at Jisr el Majami should be similarly guaranteed.

10. Exchange of Land and Population

If Partition is to be effective in promoting a final settlement it must mean more than drawing a frontier and establishing two States. Sooner or later there should be a transfer of land and, as far as possible, an exchange of population.

The Treaties should provide that, if Arab owners of land in the Jewish State or Jewish owners of land in the Arab State should wish to sell their land and any plantations or crops thereon, the Government of the State concerned should be responsible for the purchase of such land, plantations and crops at a price to be fixed, if requires, by the Mandatory Administration. For this purpose a loan should, if required, be guaranteed for a reasonable amount.

The political aspect of the land problem is still more important. Owing to the fact that there has been no census since 1931 it is impossible to calculate with any precision the distribution of population between the Arab and Jewish areas; but, according to an approximate estimate, in the area allocated to the Jewish State (excluding the urban districts to be retained for a period under Mandatory Administration) there are now about 225,000 Arabs. In the area allocated to the Arab State there are only about 1,250 Jews; but there are about 125,000 Jews as against 85,000 Arabs in Jerusalem and Haifa. The existence of these minorities clearly constitutes the most serious hindrance to the smooth and successful operation of Partition. If the settlement is to be clean and final, the question must be boldly faced and firmly dealt with. It calls for the highest statesmanship on the part of all concerned.

A precedent is afforded by the exchange effected between the Greek and Turkish populations on the morrow of the Greco-Turkish War of 1922. A convention was signed by the Greek and Turkish Governments, providing that, under the supervision of the League of Nations, Greek nationals of the Orthodox religion living in Turkey should be compulsorily removed to Greece, and Turkish nationals of the Moslem religion living in Greece to Turkey. The numbers involved were high–no less than some 1,300,000 Greeks and some 400,000 Turks. But so vigorously and effectively was the task accomplished that within about eighteen months from the spring of 1923 the whole exchange was completed. The courage of the Greek and Turkish statesmen concerned has been justified by the result. Before the operation the Greek and Turkish minorities had been a constant irritant. Now Greco-Turkish relations are friendlier than they have ever been before.

In Northern Greece a surplus of cultivable land was available or could rapidly be made available for the settlement of the Greeks evacuated from Turkey. In Palestine there is at present no such surplus. Room exists or could soon be provided within the proposed boundaries of the Jewish State for the Jews now living in the Arab area. It is the far greater number of Arab who constitute the major problem; and, while some of them could be re-settled on the land vacated by the Jews, far more land would be required for the re-settlement of all of them. Such information as is available justifies the hope that the execution of large-scale plans for irrigation, water-storage, and development in Trans-Jordan, Beersheba and the Jordan Valley would make provision for a much larger population than exists there at the present time.

Those areas, therefore, should be surveyed and an estimate made of the practical possibilities of irrigation and development as quickly as possible. If, as a result, it is clear that a substantial amount of land could be made available for the re-settlement of Arabs living in the Jewish area, the most strenuous efforts should be made to obtain an agreement for the transfer of land and population. In view of the present antagonism between the races and of the manifest advantage to both of them for reducing the opportunities of future friction to the utmost, it is to be hoped that the Arab and the Jewish leaders might show the same high statesmanship as that of the Turks and the Greeks and make the same bold decision for the sake of peace.

The cost of the proposed irrigation and development scheme would be heavier than the Arab State could be expected to bear. Here again the British people it is suggested, would be willing to help to bring about a settlement; and if an arrangement could be made for the transfer, voluntary or otherwise, of land and population, Parliament should be asked to make a grant to meet the cost of the aforesaid scheme.

If it should be agreed to terminate the Mandate and establish a Treaty System on a basis of Partition, there would be a period of transition before the new regime came into force, and during this period the existing Mandate would continue to be the governing instrument of the Palestine Administration. But the recommendations made in Part II of the Report as to what should be done tinder the existing Mandate presupposed its continuance for an indefinite time and would not apply to so changed a situation as the prospect of Partition would bring about.

The following are recommendations for the period of transition:–

- Land.–Steps should be taken to prohibit the purchase of land by Jews within the Arab Area (i.e., the area of the projected Arab State) or by Arabs within the Jewish Area (i.e., the area of the projected Jewish State).

The settlement of the plain-lands of the Jewish Area should be completed within two years.

- Immigration.–Instead of the political “high-level” there should be a territorial restriction on Jewish immigration. No Jewish immigration into the Arab Area should be permitted. Since it would therefore not affect the Arab Area and since the Jewish State would soon become responsible for its results, the volume of Jewish immigration should be determined by the economic absorptive capacity of Palestine less the Arab Area.

- Trade.–Negotiations should be opened without delay to secure the amendment of Article 18 of the Mandate and to place the external trade of Palestine upon a fairer basis.

- Advisory Council.–The Advisory Council should, if possible, be enlarged by the nomination of Arab and Jewish representatives; but, if either party refused to serve, the Council should continue as at present.

- Local Government.–The municipal system should be reformed on expert advice.

- Education.–A vigorous effort should be made to increase the number of Arab schools. The “mixed schools” situated in the area to be administered under the new Mandate should be given every support, and the possibility of a British University should be considered, since those institutions might play an important part after Partition in helping to bring about an ultimate reconciliation of the races.

Chapter X. – Conclusion

Considering the attitude which both the Arab and the Jewish representatives adopted in giving evidence, the Commission think it improbable that either party will be satisfied at first sight with the proposals submitted for the adjustment of their rival claims. For Partition means that neither will get all it wants. It means that the Arabs must acquiesce in the exclusion from their sovereignty of a piece of territory, long occupied and once ruled by them. It means that the Jews must be content with less than the Land of Israel they once ruled and have hoped to rule again. But it seems possible that on reflection both parties will come to realize that the drawbacks of Partition are outweighed by its advantages. For, if it offers neither party all it wants, it offers each what it wants most, namely freedom and security.

The advantages to the Arabs of Partition on the lines we have proposed may be summarized as follows:–

- They obtain their national independence and can co-operate on an equal footing with the Arabs of the neighbouring countries in the cause of Arab unity and progress.

- They are finally delivered from the fear of being swamped by the Jews, and from the possibility of ultimate subjection to Jewish rule.

- In particular, the final limitation of the Jewish National Home within a fixed frontier and the enactment of a new Mandate for the protection of the Holy Places, solemnly guaranteed by the League of Nations, removes all anxiety lest the Holy Places should ever come under Jewish control.

- As a set-off to the loss of territory the Arabs regard as theirs, the Arab State will receive a subvention from the Jewish State. It will also, in view of the backwardness of Trans-Jordan, obtain a grant of £2,000,000 from the British Treasury; and, if an agreement can be reached as to the exchange of land and population, a further grant will be made for the conversion, as far as may prove possible, of uncultivable land in the Arab State into productive land from which the cultivators and the State alike will profit.

The advantages of Partition to the Jews may be summarized as follows:–

- Partition secures the establishment of the Jewish National Home and relieves it from the possibility of its being subjected in the future to Arab rule.

- Partition enables the Jews in the fullest sense to call their National Home their own; for it converts it into a Jewish State. Its citizens will be able to admit as many Jews into it as they themselves believe can be absorbed. They will attain the primary objective of Zionism–a Jewish nation, planted in Palestine, giving its nationals the same status in the world as other nations give theirs. They will cease at last to live a minority life.

To both Arabs and Jews Partition offers a prospect–and there is none in any other policy–of obtaining the inestimable boon of peace. It is surely worth some sacrifice on both sides if the quarrel which the Mandate started could he ended with its termination. It is not a natural or old-standing feud. The Arabs throughout their history have not only been free from anti-Jewish sentiment but have also shown that the spirit of compromise is deeply rooted in their life. Considering what the possibility of finding a refuge in Palestine means to man thousands of suffering Jews, is the loss occasioned by Partition, great as it would be, more than Arab generosity can bear? In this, as in so much else connected with Palestine, it is not only the peoples of that country who have to be considered. The Jewish Problem is not the least of the many problems which are disturbing international relations at this critical time and obstructing the path to peace and prosperity. If the Arabs at some sacrifice could help to solve that problem, they would earn the gratitude not of the Jews alone but of all the Western World.

There was a time when Arab statesmen were willing to concede little Palestine to the Jews, provided that the rest of Arab Asia were free. That condition was not fulfilled then, but it is on the eve of fulfilment now. In less than three years’ time all the wide Arab area outside Palestine between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean will be independent, and, if Partition is adopted, the greater part of Palestine will be independent too.

As to the British people, they are bound to honour to the utmost of their power the obligations they undertook in the exigencies of war towards the Arabs and the Jews. When those obligations were incorporated in the Mandate, they did not fully realize the difficulties of the task it laid on them. They have tried to overcome them, not always with success. The difficulties have steadily become greater till now they seem almost insuperable. Partition offers a possibility of finding a way through them, a possibility of obtaining a final solution of the problem which does justice to the rights and aspirations of both the Arabs and the Jews and discharges the obligations undertaken towards them twenty years ago to the fullest extent that is practicable in the circumstances of the present time.

RSS

RSS

[…] resolutions. After months of research and interviews of major Zionist and Arab leaders, the Commission published its report in July of 1937. The report recommended a partition plan for separate Arab and Jewish states; but […]