![]()

Fri, Nov 25, 2011 | Middle East Forum | by Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

The Coming Oil-Shale Revolution?

Originally published in the Israel National News.

To preface, when it comes to global petroleum supplies, a distinction is drawn between “conventional” and “unconventional” oil reserves. The former are still in abundance in oil fields throughout the Middle East, and petroleum is produced from them simply by drilling at oil wells. Unconventional reserves include tar sands and oil shale: the latter is a form of sedimentary rock that must first be decomposed at high temperatures before crude oil can be obtained for refinement.

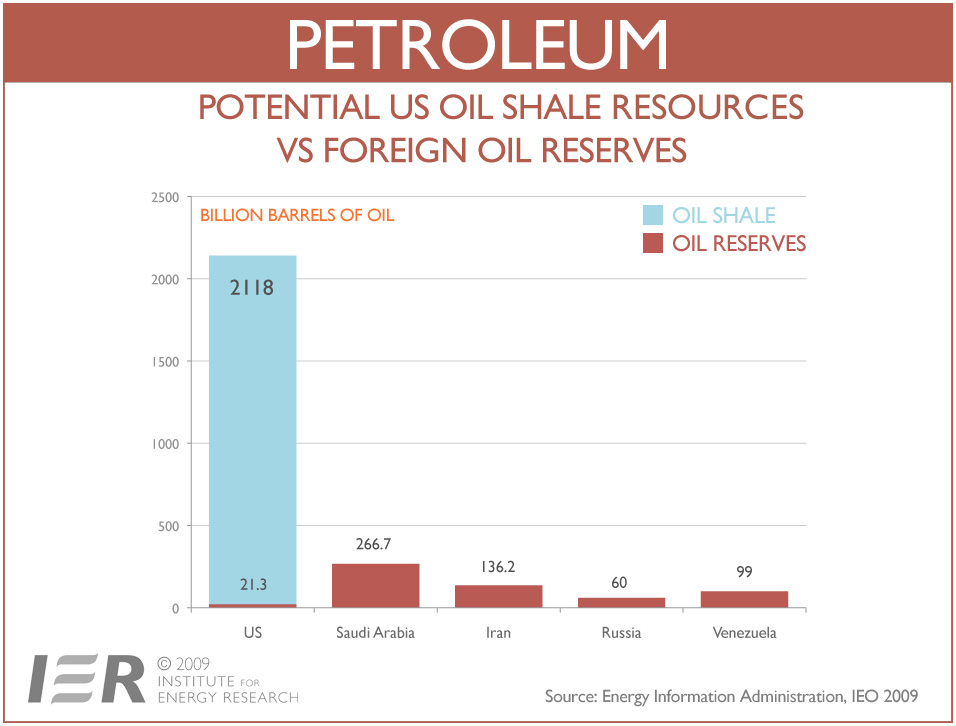

In terms of reserves, it is estimated that conventional sources across the world can yield around 1.2 trillion barrels, while in the United States alone, anywhere between 500 billion and 1.1 trillion barrels are thought to be recoverable from oil shale. An immediately astonishing observation to draw is the low-end of the estimates for U.S. oil shale, which is still around twice as large as Saudi Arabia’s total reserves.

What makes this issue particularly relevant now is the emergence of reports on a potential breakthrough in oil shale extraction technology. Traditionally, extraction of oil shale has required the use of a method known as “fracking,” or “hydraulic fracturing” (to use the more technical term).

Hydraulic fracturing, however, has raised concerns because of issues such as contamination of groundwater and air pollution, besides the large amounts of water required for the process. The high water usage is particularly problematic in the Southwestern states that contain most of the United States’ oil shale reserves and are under water stress owing to drought in recent years.

Nonetheless, companies such as Chevron are now looking into the use of propane gel rather than water. Not only does this method require no water, but it also makes more sense from a technical point of view. As one former Halliburton Co engineer pointed out, “It’s an ideal liquid to crack the rock open with because it does not damage the rock like water would.” Accordingly, this pioneering process, despite some worries over propane gel’s flammability, is increasingly being given the green light by regulators in Canada and the United States.

In light of these developments, the chief executive of Saudi Arabia’s state-owned oil company — Aramco — has come to acknowledge that the development of large oil shale reserves in North America looks set to shift the monopoly over global energy supplies increasingly away from the Middle East. Indeed, Saudi Arabia has now halted a $100 billion expansion program that aims to expand Saudi output to 15 million barrels per day (bpd) by 2020.

Meanwhile, China is expected to be producing 1.1 million bpd of unconventional oil by 2035 (as opposed to 6.6 million bpd from the United States and Canada), a petroleum firm has announced the discovery of significant oil shale reserves in Argentina, and various companies have reported success in drilling wells for extracting natural gas from shale rocks in Poland.

Naturally, the following question arises: Are we finally moving into an era of complete energy independence from the Middle East and OPEC? If so, what are the implications?

As regards the former question, there is still one sign that appears to point to uncertainty. Despite anticipated increases in oil shale production, the fact remains that conventional oil will always be much cheaper to extract and use. Linked to this point is the International Energy Agency’s recent report that predicts Iraq will be the largest contributor to the growth in global oil production over the next 25 years. Iraqi crude, like that in Saudi Arabia, is perhaps the least expensive oil to extract in the world at only a few dollars per barrel.

Since state-control (which still exists) over the Iraqi oil industry and international sanctions have meant that for many years Iraq has produced oil largely for domestic consumption, there is still potential for exploration and discovery of new reserves in the country, hence, for instance, the recent exploration deal signed between ExxonMobil and the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq.

Since the 2003 invasion, Iraq has been able to secure numerous contracts with foreign firms in an effort to undergo a massive expansion in production for the international market, and output can only be expected to increase over the coming years. Peak oil for Iraq is not expected to occur until at least 2036.

Nonetheless, questions have been raised over export capacity hindered by outdated infrastructure. Perhaps paradoxically, the increased oil revenues for the Iraqi government mean that Baghdad is unlikely to shift towards liberalizing economic reforms, which in turn will continue the problem of excessive bureaucracy that impedes reconstruction and updating of infrastructure.

In any case, regardless of whether the West achieves energy independence from the Middle East, Saudi Arabia’s profits (as well as those of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates) from the oil industry will probably diminish in light of competition from Iraq and oil shale across the world. In this context, commentators will no doubt be wondering if these developments will mark a decline in Islamism around the world.

In fact, what Daniel Pipes terms the “Islamic revival” coincided with the surge in oil prices in the 1970s and 1980s, and so many analysts have drawn a major link between the two events. End the oil dependence, so the reasoning goes, and Saudi Arabia will be exhausted of petrodollars to fund and spread its Wahhabi ideology.

However, I remain skeptical of such claims, which appear to reduce simplistically the growth in Islamist ideology to a single cause. Of course, funds from Saudi Arabia have led to an upsurge in the Wahhabism in countries like Bosnia, where an individual influenced by the Wahhabi movement growing in Bosnia — Mevlid Jasarevic — opened fire on the American embassy in Sarajevo.

Nonetheless, Islamism is ultimately a problem rooted in questions of “identity and circumstance” (as Pipes puts it), and in the age of mass communication, it is much easier for those who draw on broad elements of traditional Islamic theology to justify doctrines of jihad as offensive warfare and imposing Islamic law to attain success in winning over peaceful Muslims to their causes.

Moreover, we see that in Egypt with the Muslim Brotherhood, Pakistan with its numerous Islamist movements, Tunisia with its an-Nahda movement, Yemen with al-Qa’ida, Somalia with ash-Shabaab, and Sudan with its regime under Omar al-Bashir (to name just a few), Islamism enjoys success without dependence on financial boosts from petroleum profits.

As Pipes noted back in 2002: “Oil revenues helped give militant Islam a start; but once up and running… it [militant Islam] no longer depends on this financial boost as shown by oil revenues having several times in the intervening years gone down without a noticeable reduction in militant Islam’s steady gains.”

In short, therefore, growing energy independence for the West via oil shale (a pleasing development in its own right) seems unlikely to hamper significantly the problem of Islamist ideology.

The only real solution — necessary, but difficult and almost certainly long-term — is honest reform within mainstream Islam to counter appeal to traditional notions of waging jihad against non-Muslims and imposing Shari’a in the public realm.

Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi is a student at Brasenose College, Oxford University, and an intern at the Middle East Forum.

RSS

RSS

The Coming Oil-Shale Revolution? | Middle East, Israel, Arab World, Southwest Asia, Maghreb http://t.co/1HTryFmb

The Coming Oil-Shale Revolution? | Middle East, Israel, Arab World, Southwest Asia, Maghreb http://t.co/1HTryFmb