![]()

Tue, April 12, 2011 | Turkey Analyst, vol. 4 no. 7 | By Gareth H. Jenkins

The Fading Masquerade: Ergenekon and the Politics of Justice in Turkey

This article was first published in the Turkey Analyst (www.turkeyanalyst.org), a biweekly publication of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center.

On the afternoon of March 30, 2011, Zekeriya Öz, the chief prosecutor in the controversial Ergenekon investigation, was abruptly removed from the case by the Turkish Justice Ministry. The decision came after a month in which allegations of links to Ergenekon had once again been used to try to silence critics of the exiled Islamic preacher Fethullah Gülen. On the morning of March 30, 2011, police acting on Öz’s orders had raided the homes and offices of seven theologians opposed to Gülen. On March 3, Öz had triggered domestic and international outrage by ordering the arrest of eleven journalists and academics who had been critical of Gülen and subsequently attempting to erase all copies of an unpublished book about him.

Background

Since it was first launched in June 2007, the Ergenekon investigation has become the largest, most expensive and most controversial case in modern Turkish history. Initially, the investigation was touted by its supporters as a milestone in the development of Turkish democracy, an opportunity for the final eradication of the shadowy networks that used to operate under the protection of state institutions and which are known in Turkish as the derin devlet or “deep state”. The influence of the deep state has declined rapidly since the late 1990s. Today, only scattered remnants remain. But there has never been a thorough investigation of its activities, particularly its involvement in the death squads that terrorized the predominantly Kurdish southeast of the country in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

However, it rapidly became clear that the real goal of the Ergenekon investigation was not to go after the deep state but to intimidate and silence opponents of Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), particularly critics of the vast network of Gülen’s supporters known as the Gülen Movement. By April 2011, over 500 people had been taken into custody and nearly 300 formally charged with membership of what prosecutors described as “the Ergenekon terrorist organization”, which they claimed had been responsible for virtually every act of political violence — and controlled every terrorist group — in Turkey over the last 30 years. The Ergenekon indictments run to thousands of pages and are filled with absurdities and contradictions. Most worryingly, they contain no convincing evidence that Ergenekon even exists, much less that the accused are members or have committed any crime. Most disturbingly, there are strong indications that some of the “evidence” in the indictments has been fabricated. [See 2009 Silk Road Paper; 18 July 2010 Turkey Analyst via CrethiPlethi; 28 September 2009 Turkey Analyst and 24 April 2009 Turkey Analyst]

From the outset, the pro-AKP media, particularly the newspapers and television channels run by the Gülen Movement such as Zaman, Today’s Zaman and Samanyolu TV, have vigorously supported the Ergenekon investigation. This has included the illegal publication of “evidence” collected by the investigators before it has been presented in court, misrepresentations and distortions of the content of the indictments and smear campaigns against both the accused and anyone who questions the conduct of the investigations.

There have long been allegations that not only the media coverage but also the Ergenekon investigation itself is being run by Gülen’s supporters. In August 2010, Hanefi Avcı, a right-wing police chief who had once been sympathetic to the Gülen Movement, published a book in which he alleged that a network of Gülen’s supporters in the police were manipulating judicial processes and fixing internal appointments and promotions. On September 28, 2010, two days before he was due to give a press conference to present documentary evidence to support his allegations, Avcı was arrested and charged with membership of an extremist leftist organization. He remains in jail. On March 14, 2011, Avcı was also formally charged with being a member of the alleged Ergenekon gang.

On February 14, 2011, four employees at an anti-AKP internet television channel called OdaTV were arrested as they prepared to broadcast footage showing police officers involved in the Ergenekon investigation apparently planting evidence at premises associated with one of the accused. All of the arrested staff from OdaTV have now been charged with membership of Ergenekon.

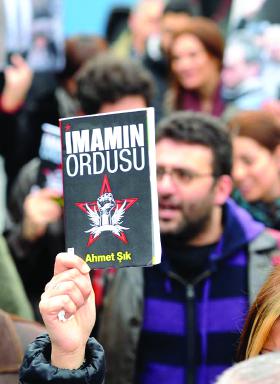

On March 3, 2011, eleven suspects, nine of them journalists, were detained in police raids ordered by Zekeriya Öz. The journalists included Nedim Şener, a reporter for the daily Milliyet who had won international press awards for his work on the alleged involvement of the security forces in political assassinations, and Ahmet Şık, a reporter for the daily Radikal. Şık had recently completed the first draft of a still unpublished book on the activities of Gülen’s supporters in the police force entitled İmamın Ordusu (“The Imam’s Army”).

Şener, Şık and the others arrested on March 3, 2011, are now in jail facing charges of belonging to Ergenekon. On March 25, 2011, the police raided the offices of Radikal and Şık’s prospective publisher. They deleted every digital copy they could find of Şık’s manuscript and displayed a court order warning that anyone found in possession of a copy would face prosecution as a member of Ergenekon.

Prosecutors refused to allow Şık’s lawyers to see a copy of the manuscript they had taken from his computer on the grounds that it had been produced by a “terrorist organization”. But this did not prevent them from leaking a 49-page police report on the book, including copious quotations, to pro-AKP newspapers, including Zaman, which duly published details on March 27, 2011.

However, Şık or someone close to him had already taken precautions. On March 31, 2011, a copy of Şık’s manuscript appeared anonymously on the internet. It immediately went viral, recording over 100,000 downloads in the first 48 hours.

Implications

Şık’s book runs to 298 pages and details the growth of the Gülen Movement from its beginning in the Mediterranean port of Izmir in the 1970s, through Gülen’s flight into exile in Pennsylvania, USA, in the late 1990s to the present day. Most of Şık’s manuscript is devoted to what he describes as the Gülen Movement’s efforts first to infiltrate and then to control the police force. Şık draws heavily on other sources, including quoting extensively from intelligence reports from before the AKP came to power in 2002 and more recent work by other journalists and analysts. As a result, the book contains little that was not already known. Nevertheless, the cumulative impact of Şık’s detailed catalogue of the manipulations of judicial processes, attempts to place sympathizers in key positions, and the false charges and smear campaigns against perceived opponents and rivals is devastating; particularly for a movement which has consistently maintained that it has no political agenda.

A protester in Istanbul holds a mock-up of an unpublished but banned book by the jailed journalist Ahmet Şık. (DHA photo)

In this context, the removal of Zekeriya Öz from the Ergenekon case represents the most serious setback for the Gülen Movement since the AKP came to power. Publicly, the AKP insists that the judiciary is independent and that the decision to dismiss Öz was taken by the Supreme Board of Judges and Prosecutors (HSYK), which oversees all judicial appointments. Privately, officials report that the decision was taken by the government.

Although the Gülen Movement has always been broadly supportive of the AKP, its relationship with Erdoğan has often been problematic. This is partly because Gülen is a follower of the idiosyncratic Kurdish Islamist Said Nursi (1876-1960), while Erdoğan is a member of the much older, and highly institutionalized, Naqshbandi Sufi order; and partly a simple question of power. Erdoğan is aware that the support of the Gülen Movement provides considerable political benefits, both domestically and internationally. Its vast network of NGOs, businesses, schools and media outlets have made the Gülen Movement arguably the most powerful non-state actor in Turkey. Internationally, its schools and NGOs have laid the foundations for Turkey’s recent attempts to expand its influence in the Balkans and Africa. The movement has also been very active in the U.S., running more than 120 charter schools in 25 states, establishing NGOs in Washington, D.C., organizing conferences and providing funding to U.S. think tanks.

Erdoğan has always been wary of a power he cannot control. He has publicly supported the Ergenekon investigation, which has intimidated and weakened his political opponents. But he has not been driving the case; often only learning of arrests after the suspects have already been taken into custody. However, in recent months, what was once a political benefit has become an embarassment; particularly as the increasingly blatant persecution of critics of the Gülen Movement has coincided with mounting international criticism of Erdoğan’s growing authoritarianism. More urgently for Erdoğan, the most recent arrests came as the AKP was preparing its campaign for the June 12, 2011 general election, in which the party will attempt to emphasize its commitment to democracy and freedom of expression.

Conclusions

Erdoğan has invested too much political capital in the Ergenekon investigation to allow it to collapse before the June 12, 2011 election. However, after the removal of Öz, prosecutors are likely to be under pressure from the AKP to avoid any more high profile arrests in the run-up to the polls.

Öz’s dismissal may also mark the beginning of a trial of strength within the AKP as Erdoğan begins to finalize the list of the party’s candidates for the June election. Erdoğan has already announced that he will attempt to introduce a new constitution after the election, replace the current parliamentary system with a presidential one and have himself elected president in place of the incumbent Abdullah Gül. Gül, who has the support of the Gülen Movement, has publicly opposed the change. As a result, Erdoğan is aware that, in order to push the new constitution through parliament, he needs a clear majority not only in the assembly but also within the AKP parliamentary party; which means reducing the number of AKP deputies who are sympathetic to Gül and/or the Gülen Movement.

It is currently unclear how the Gülen Movement will respond to Erdoğan’s attempts to assert his authority or to its increasingly close association in the public perception with attempts to suppress freedom of expression. Ironically, the zeal with which Öz — supported by the Gülen media — has persecuted the movement’s opponents has probably done more to tarnish its domestic and international reputation than the criticism, such as in Şık’s book, that it has attempted to suppress.

About the author,

Gareth Jenkins, a Senior Associate Fellow with the CACI & SRSP Joint Center, is an Istanbul-based writer and specialist of Turkish Affairs.

RSS

RSS

The Fading Masquerade: #Ergenekon and the Politics of Justice in #Turkey | #AKP #Erdogan #Gülen http://j.mp/gTwXse

The Fading Masquerade: #Ergenekon and the Politics of Justice in #Turkey | #AKP #Erdogan #Gülen http://j.mp/gTwXse

The Fading Masquerade: Ergenekon and the Politics of Justice in Turkey | Middle East news, articles, http://fb.me/WwV7l7EB

RT @CrethiPlethi: The Fading Masquerade: #Ergenekon and the Politics of Justice in #Turkey | #AKP #Erdogan #Gülen http://j.mp/gTwXse

RT @CrethiPlethi: The Fading Masquerade: Ergenekon and the Politics of Justice in Turkey | Middle East news, articles, http://fb.me/WwV7l7EB

The Fading Masquerade: #Ergenekon and the Politics of Justice in #Turkey http://j.mp/ihwRkh by @GarethJenkins #CHP #AKP #Erdogan

Good analysis by Gareth Jenkins RT @HansAHCdeWit The Fading Masquerade: #Ergenekon and the Politics of Justice in #Turkey http://j.mp/ihwRkh

The Fading Masquerade: Ergenekon and the Politics of Justice in Turkey http://j.mp/ihwRkh

The Fading Masquerade: Ergenekon and the Politics of Justice in Turkey http://j.mp/ihwRkh via @AddToAny