![]()

Sun, June 19, 2011 | The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center

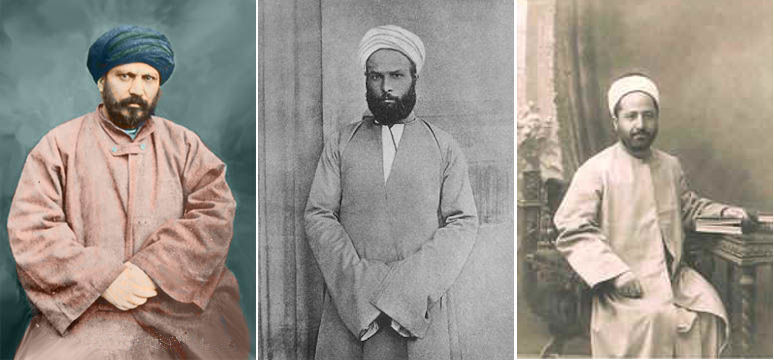

left: Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1838-1897); middle: Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905); right: Muhammad Rashid Rida (1865-1935)

The Muslim Brotherhood – Chapter 2: The ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood

The Muslim Brotherhood is an Islamic mass movement whose worldview is based on the belief that “Islam is the solution” and on the stated aim of establishing a world order (a caliphate) based on Islamic religious law (Shariah) on the ruins of Western liberalism. With extensive support networks in Arab countries and, to a lesser extent, in the West, the movement views the recent events in Egypt as a historic opportunity. It strives to take advantage of the democratic process for gradual, non-violent progress towards the establishment of political dominance and the eventual assumption of power in Egypt and other Middle Eastern countries.

Since its very beginning, the Muslim Brotherhood was based on ideological foundations that first emerged as a result of disenchantment with the idea of “Islamic reformism”. Advocates of the idea, which appeared in the second half of the 19th and early 20th century, sought to have Muslim society undergo a rapid Western modernization and reform the religion of Islam.

According to Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1838-1897) and Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905), the founders of this school of thought, the modernization they sought was to be based on a comprehensive adoption of technology, social structure, and even way of life prevailing in the West at the time, only clothed in Islamic garb. This required deep, substantial reforms in Islam and its institutions.

As part of the proposed changes, the reformists sought to abolish the principle of “taqlid” (“tradition”, i.e., blind imitation of past customs) and adopt the principles of Islamic religious law to modern demands. They considered the religious-legal restraints that interfere with modernization to be “harmful additions” added to Islam over the centuries, believing that Islam should be liberated from them through innovations (some of them far-reaching) in religious law.

For example, Muhammad Abduh wanted to grant equal rights to women, particularly in education, and argued for the need to draw know-how and technology from the West without considering it to be “bid’ah” (a change that contradicts religious law and is therefore prohibited).

The ideas of Afghani and Abduh may be viewed as an attempt to promote a gradual process of Westernization, stemming from their belief that Western societies were the most advanced and that emulating them was a goal to be achieved. These ideas, however, did not gain extensive support in the Islamic world. It was their successor, Muhammad Rashid Rida (in 1865-1935) who started calling for a reexamination of his predecessors’ ideas. Like them, he considered the Muslim world to be weak compared to the West, yet his suggested method of rectifying the situation was different: instead of Westernization, a return to the roots of Islam, the implementation of Islamic religious law (Sharia), and the establishment of a Sharia state.

Hassan al-Banna, the founder of the modern Muslim Brotherhood movement, was highly influenced by Rashid Rida’s thought, and developed his ideas into a social organization dedicated to the implementation of those principles. Alongside the Muslim Brotherhood’s rapid expansion in the 1930s, Al-Banna wrote five risalat (letters) to his young, educated supporters. The ideas he set forth in the letters are still the pillars of the movement’s worldview.

In his ideological messages, Al-Banna defined his movement as a group of believers on a quest for the revival of Islam, seeking to establish a Sharia state based on the Quranic “law of Allah”. It is an objective Al-Banna hoped to achieve by liberating the Muslim world from any kind of foreign rule, followed by shaping a state governed by Islamic religious law. According to Al-Banna, the establishment of such a state is not the final goal. On the contrary, the new Sharia state must realize its social order in accordance with Islamic religious law and become a basis for the worldwide spread of Islam, eventually culminating in the emergence of Islamic hegemony around the globe.

Al-Banna listed seven stages to achieve these objectives, each to be carried out in a gradual fashion. The stages are divided into social and political: the first three are based on educating the individual, the family, and the entire society of the Muslim world to implement Sharia laws in every aspect of daily life. The next four stages are political by nature, and include assuming power through elections, shaping a Sharia state, liberating Islamic countries from the burden of (physical and ideological) foreign occupation, uniting them into one Islamic entity (“new caliphate”), and spreading Islamic values throughout the world.

The principle of liberating the world of Islam from the occupation of foreign powers has particular implications for the Muslim Brotherhood’s stance towards Israel, whose establishment is considered by the movement members an integral part of the Western plot to conquer and bring division into the world of Islam. They categorically deny Israel’s right to exist, and express vociferous opposition to any indication of normalization in relations with it. It appears that this principle is welcomed by all Muslim Brotherhood activists, regardless of time or location (see Chapter 6 for details).

Al-Banna’s principles still constitute the ideological foundation of the Muslim Brotherhood.[23] However, there occurred considerable developments in the validity of his ideological message since the end of World War II. The change stemmed mostly from the appearance of radical Muslim Brotherhood factions in Egypt following the mass arrests of their members by Nasser’s regime in the 1950s and 1960s, and the lifting of restrictions on their political participation in various Arab countries since the 1970s.

The growth of the Muslim Brotherhood’s radical faction is associated with Sayyid Qutb (1906-1966), a senior ideologue in the movement’s Egyptian branch. In the 1950s and 1960s, Qutb wrote several books (some during his prison term) supplementing Al-Banna’s ideas with a radical spirit. Thus, he developed the idea of “modern jahiliyya”,[24] according to which modern Islamic society is ignorant and has strayed from the code of conduct required by divine precepts. In this context, Qutb discussed the phenomenon of Westernization, as well as the existence of regimes based on earthly, man-made legal systems. Accordingly, in Qutb’s view the Arab regimes were considered as lacking religious and divine legitimacy (which he considered a supreme value), and thus he publicly called to resist these regimes.

Even though Qutb did not emphasize that resistance to the regimes must be violent, he created an opening for such violent activity by defining jihad for the enforcement of religious law (Sharia) in Muslim society as every Muslim’s duty. Qutb’s execution in 1966, which many saw as shahada (martyrdom for the sake of Allah), served to further disseminate his ideas. Starting from the 1970s, these ideas gained even more popularity thanks to the educational activity of his supporters, who came to Saudi Arabia and linked Qutb’s principles to those of Salafism[25] and Wahhabism. Later, this link gave rise to the idea of global jihad and takfir (accusing others of infidelity).

Alongside the radical ideology of Qutb and his successors, another faction developed starting from the mid-1980s, also originating in the ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood. It is the Wasatiyya (middle ground) faction, mostly associated with a well-known Qatari cleric of Egyptian descent, Yusuf al-Qaradawi. This faction supports the idea of adjusting Islam to modern reality and religious tolerance, strongly opposes the idea of global jihad, and attempts to give religious-legal validity to changes resulting from the adoption of modern technology, social modernization (in women’s status, for example) and the need to contend with the influence of other cultures (as part of life in immigrant communities, among other things).

The messages of this school of thought focus mostly on the attempt to fight the spiritual influence of the followers of global jihad. However, despite the fact that it contains different liberal ideas, this faction’s adherence to the fundamental principles of the Sharia, without implementing a comprehensive reform in the Muslim worldview, reflects a desire to “conquer Rome” (i.e., victory over the West) and reiterates vicious anti-Semitic views. The faction supports terrorism (including suicide bombings and murder of civilians) “only” against Israel and the occupation in Iraq, while the struggle as a whole — against Middle Eastern and Western regimes — should take place through the da’wah and without the use of violence (see Chapter 11 for Qaradawi’s profile).

Since the Muslim Brotherhood supports the worldwide spread of Sunni Islam, it shares the Sunni-Shi’ite debate. Early on, the Muslim Brotherhood considered the Shi’ites an inseparable part of the Muslim nation, and even expressed support for the Islamic revolution in Iran. Afterwards, the Muslim Brotherhood’s attitude towards Iran grew much more hostile due to Iran’s efforts to export the revolution to the Sunni Arab domain. In recent years, and all the more so since the second Lebanon war, the question of the attitude towards the Shi’ites has reemerged once again. In general, the basis for the debate is the difference in the perception of Iran’s political role in the region.

Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood has not reached an agreement on the stance towards Iran. Some members of the Muslim Brotherhood leadership in Egypt lead support for Iran as the “engine of resistance”, making official Egyptian observers claim that the movement’s leadership attempts to find ways to strengthen its ties with Iran to form an alliance against the Egyptian regime. On the other side of the fence are Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi, who on several occasions has expressed concerns over the threat of “Shi’itization” of Sunni population in Arab countries, and the leadership of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood, which considers Iran an ally of Assad’s oppressive regime, responsible for the brutal suppression of the movement in Syria.

Ultimately, it appears that the Muslim Brotherhood’s stance to the Shi’ites is one of ambivalence. This is a result of the built in tension between its fundamental support for the idea of “resistance”, currently led by Shi’ite Iran and implemented, among others, by Hamas, and its character as a Sunni organization par excellence, requiring a certain level of commitment to Sunni traditions that don’t take kindly to the Shi’ite faith.

This comprehensive analysis of the Muslim Brotherhood (by ITIC) consists of 12 chapters. All 12 chapters are listed below:

Chapter 1: The historical evolution of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt

Chapter 2: The ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood

Chapter 3: The Muslim Brotherhood’s education, preaching, and social activity

Chapter 4: The structure and funding sources of the Muslim Brotherhood

Chapter 6: The Muslim Brotherhood’s stance on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict

Chapter 7: The development of political discourse in the Muslim Brotherhood and the 2007 election platform

Chapter 8: Profiles of prominent Muslim Brotherhood figures in Egypt

Chapter 9: The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood’s ties to its branches in Middle Eastern and Western countries

Chapter 10: The Muslim Brotherhood in other Arab countries and in Europe

Chapter 11: A profile of Sheikh Dr. Yusuf al-Qaradawi

Chapter 12: Islamic jihadist organizations in Egypt ideologically originating in the Muslim Brotherhood

You can download the full study in PDF-format here

Note:

[23] Al-Banna’s five letters have a special place on the official website of the Muslim Brotherhood, whose leaders have often stressed their adherence to the letters’ principles in recent years.

[24] Jahiliyya — the period of “ignorance” that preceded the appearance of Islam in the Arab Peninsula.

[25] Salafism — a movement in Islam that considers the Quran and the Sunna the highest legal authorities and calls to build the life of the Muslim nation on a literal understanding of the Quranic text and on the practices of the first three pious generations of the nation (Salaf).

RSS

RSS

The ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood | #Egypt #Islamism http://bit.ly/pwLUBJ

The ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood | #Egypt #Islamism http://bit.ly/pwLUBJ

The ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood | #Egypt #Islamism http://bit.ly/pwLUBJ

[…] Chapter 2: The ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood […]