![]()

Sun, June 23, 2013 | The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center

The escalating anti-Shi’ite rhetoric from Sunni clerics belonging to different schools of thought reflects an agreement that the Shi’a is the enemy of the moment — one that is more pressing than the West and Israel.

Overview

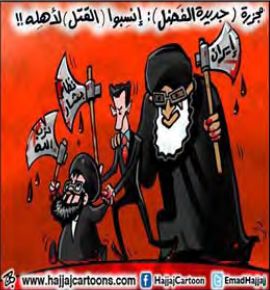

Ali Khamenei, Bashar Asad, and Hassan Nasrallah depicted as incarnations of Satan (arabsnews.net, May 28, 2013)

The depth of the Sunni-Shi’ite schism can be seen in all the major arenas where regional conflicts are being waged. It is reflected in Hezbollah’s growing involvement in the fighting in Syria, the spilling over of the Syrian civil war into Lebanon, record-breaking sectarian violence in Iraq, and the aggressive stance taken by the Persian Gulf states towards Iran and Hezbollah. Thus, the Sunni-Shi’ite schism is emerging as one of the most influential factors shaping the Middle East in a time of regional upheaval.

A major force driving the schism is the escalating anti-Shi’ite rhetoric from Sunni clerics who belong to different schools of thought. Of particular note is a speech given on May 31, 2013 by Sheik Yusuf al-Qaradawi, considered by many the current spiritual leader of the Sunni world, in which he said he regretted the many years he had spent on attempts at Sunni-Shi’ite rapprochement. He said that Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabi clerics were right to consider Shi’ites as infidels, and adopted their terminology when talking about the Shi’a (“Hezbollah is the Party of Satan”).[1]

The escalating rhetoric is reminiscent of the sentiments in the Sunni world towards the Shi’a during previous “waves”, such as the disillusionment that followed the Islamic revolution in Iran, the campaign in Iraq, and the second Lebanon war. It reflects an agreement — shared by shari’a teachers affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, the Wahhabi establishment, Salafi preachers, and jihadists — that the Shi’a is the enemy of the moment.

The meaning of that escalation is that, ideologically speaking, the fight against the Shi’a (and its representatives, Iran and Hezbollah) takes precedence over the fight against the West and Israel — although it does not mean that the fight will necessarily be backed by actual on-the-ground efforts. This coincides with the political and social reality brought about by the regional upheaval: a widening of the fundamental fault lines that run through the Arab and Muslim world.

Appendix I

Taqrib al-Madhaheb (Rapprochement of the Schools of Thought): Death of a vision

The idea of Sunni-Shi’ite rapprochement is normally associated with the Society for Rapprochement between Islamic Schools of Thought (Jama’at al-Taqrib bayn al-Madhaheb), which worked in Egypt in the middle of the previous century. In 1959, Shaltut, who was the Sheik of Al-Azhar at the time, issued a fatwa (religious ruling) stating that the Shi’a is “a school of thought that is religiously correct to follow as other Sunni schools of thought.” In the fatwa, Shaltut referred to the Shi’a as “al-madhhab al-ja’fari” — the Ja’fary school of thought, after the Sixth Imam of the Twelfth Shi’a, who is believed to have established the principles of Shi’ite theology. It was a first Sunni recognition of the Shi’a as a legitimate religious-juridical and theological school of thought, alongside the four Sunni schools of thought.

The fatwa issued by Shaltut — a cleric of the establishment who, in his official capacity, served the goals of the Egyptian regime and was a mouthpiece for its wishes — was obviously politically motivated and made-to-order. It was intended to help Nasser form a closer relationship with Qassem’s predominantly Shi’ite Iraq at the time.

Shaltut, considered a key figure among those who support the Sunni-Shi’ite rapprochement, is also said to be the one who decided to introduce Shi’ite law into the Al-Azhar curriculum as an integral part of education on Islamic schools of thought. However, the decision was phrased vaguely, and in practice Shi’ite law was only taught under comparative law and not as a separate school of thought. Once again, the pro-rapprochement stance was primarily the result of political expediency. This was reflected in the decline of the rapprochement movement in the 1960s in light of political tensions between Egypt and Iran.

The view that is opposed to rapprochement is similarly rooted in political factors. For instance, the fatwa issued by the Wahhabi Saudi cleric Abdullah ibn Jibreen in the first week of the second Lebanon war cannot be separated from Saudi Arabia’s stance towards Hezbollah and the deep-rooted historical animosity between the Wahhabis and the Shi’ites. In his fatwa, Ibn Jibreen called on the Sunnis to denounce the Shi’ites, said that helping “that infidel [min al-rafidhin] party [Hezbollah]” was forbidden, and concluded with a verse from the Quran: “And whoever is an ally to them among you — then indeed, he is [one] of them” (Surat al-Maidah, Verse 51). The verse originally refers to a ban on befriending Christians and Jews, and was extended by Ibn Jibreen to include the Shi’ites.

As was the case with other fatwas that stirred controversies in the Muslim world, Ibn Jibreen and his allies tried to do “damage control” and retract the fatwa. The websites of Ibn Jibreen’s son and students posted an apology of sorts, saying that the remarks were “taken out of context”. Nevertheless, that back-and-forth could not conceal the clarity and firmness of the fatwa as a true manifestation of Wahhabism, which subscribes to the uniqueness and unity of God and therefore considers the Shi’a to be guilty of the greatest sin: worship of more than one god (shirk).

One of the most notable, interest-provoking reactions in the Sunni world to Ibn Jibreen’s fatwa was a counter-fatwa issued by Sheik Yusuf al-Qaradawi, affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood and considered by many the current spiritual leader of the Sunni world. Al-Qaradawi ruled that anyone who pronounces the two creeds — “There is no god but Allah and Muhammad is the messenger of Allah” — is a Muslim for all intents and purposes and will not see the fires of Hell. According to Al-Qaradawi, therefore, the Shi’ites are Muslims, too, and their addition to the creed — “and Ali is the wali (friend, viceregent) of Allah” — takes nothing away from that.

Al-Qaradawi based his fatwa on a hadith attributed to Prophet Muhammad, a cornerstone of the idea of jihad: “I have been commanded (by Allah) to fight the infidels, until they testify that there is no god but Allah and Muhammad is His messenger. If they do, I will not harm them or their property, since from now on they are immune and it is only for Allah to judge them.” According to Al-Qaradawi, it is in the branches that Shi’ites and Sunnis differ, not in the roots, meaning that the differences between them are minor.

Al-Qaradawi’s apologetic fatwa on the Shi’a was a reflection of his religious and political interest to sanctify the struggle against the West and the Jews. In his view, the enemies on the outside — the Jews, the Christians, and the pagans — have created an anti-Islamic front, which is why the Shi’ites and the Sunnis cannot sit idly by and have to create their own front against the enemy. His argument that the disagreement between the two schools of thought is not about the basic tenets of faith but rather about things of little consequence is incorrect; however, it did serve his political objectives at the time.

Loyal to his approach, in 2005 Al-Qaradawi issued a “declaration of principles for dialogue and rapprochement between the Shi’ites and the Sunnis”, a document detailing ten principles aimed to bring about rapprochement (taqrib). One of them, for instance, is the principle of good mutual understanding: Al-Qaradawi stated that a distinction should be drawn between things agreed upon by all Shi’ites and things on which they disagree. Controversial issues within the Shi’ite school of thought itself may form a basis for rapprochement between certain parts (or perhaps even most) of the Shi’a and the Sunna. Such a distinction can be drawn only if each side understands the other’s tenets of faith by studying its established religious legal texts — certainly not on the basis of rumors, myths, and outward behavior displayed by the other side.

For instance, Al-Qaradawi said that if the Sunnis were to delve into the Shi’ite view of the Quran, they would discover that only a minority of Shi’ites believe that the Quran has been distorted by the Sunnis — most Shi’ites accept the Quran as it is and make no claims that it has been distorted, only that its most authoritative interpretation is the one given by Ali. It is therefore Al-Qaradawi’s belief that this has to become a common ground for the Sunnis and the Shi’ite majority to come together and reach an agreement that the Quran is the living word of God, “untouched by blasphemy”. The fact is, Al-Qaradawi added, that a Quran printed in Iran is the same as one printed in Saudi Arabia or Egypt.

Another principle in Al-Qaradawi’s “rapprochement philosophy” document is focusing on areas where the Shi’a and the Sunna are in agreement, both in the pillars of faith (arkan al-iman) and in the pillars of practice (arkan al-islam). Al-Qaradawi thus plays down the considerable differences in hadith and Quran interpretation that do not serve his purposes, attempting to cover them up.

In recent years Al-Qaradawi has launched various activities to promote the idea of rapprochement, some of whose partners have been Iranian clerics belonging to Iran’s Shi’ite rapprochement organization, working under the Supreme Leader’s office. While those activities — mostly conferences or joint appearances in inter-Arab media — have served as a platform for furthering interests shared by both parties, they have also laid bare the differences between them.

For instance, Al-Qaradawi spoke out against the phenomenon of “Shi’ite evangelism” and the Shi’ization of countries with a Sunni majority. He also condemned the Shi’ite custom of cursing the three first caliphs and the Prophet’s companions, considered role models in Sunni Islam, going as far as to demand that his Iranian colleagues issue a fatwa explicitly banning the practice. On the other hand, the Iranian clerics, particularly Ayatollah Taskhiri, the head of the Iranian organization for rapprochement, demanded that the Sunnis denounce the idea of takfir (accusations of heresy, frequently targeted at Shi’ites). In other words, the rapprochement efforts have often backfired.

The inutility of the rapprochement discourse in the past few years, coupled with the regional upheaval which has made it all the more clear that the West and Israel (considered by Al-Qaradawi to be the chief enemies) are not the issue in the region, has stripped the rapprochement of its political relevance. And in the meantime, the regional upheaval is becoming polarized along the traditional fault lines of the Middle East, particularly the violent Sunni-Shi’ite conflict.

With this in mind, it appears that Al-Qaradawi’s recent misgivings about the idea of rapprochement itself and his admission that Sheik Jibreen and his likes had the right idea have closed the door — at least for the next several years — on a dialogue that was far from being representative of the Sunni “hard core” to begin with.

Appendix II

The anti-Shi’ite discourse in radical Sunni Islam: from scripture to sword

When a radical group defines its “other”, delineating its own identity becomes easier. This gives rise to the notion that “homegrown” sinners, those who threaten the community from the inside, are worse and more dangerous than other sinners. It is for this reason that Sunni radicals consider the Shi’a worse than Christianity or Judaism.

There is now a massive body of literature in the Sunni world filled with hatred of the Shi’a, but it was not always like this. The Ottomans, for example, believed that the Shi’ites were sinners and discriminated against them, but still considered them Muslims. They only persecuted extremist Shi’ites, but did not harm mainstream Twelver Shi’ites. The Wahhabis in the Arabian Peninsula were the exception, even in Ottoman times. They were notable for categorically rejecting the Shi’a as heresy against the uniqueness and unity of God (tawhid).

The Islamic awakening that began with Sayyid Qutb and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and later continued in Afghanistan and Iran brought the sectarian tensions back to life. At first, the Sunni religious movements supported the Iranian revolution; however, their support dwindled as the revolution’s pronounced Shi’ite character became clearer. Their renouncement of the revolution reached its apogee after Iran’s Islamic regime provided support to the Syrian regime when the latter massacred the Muslim Brotherhood in Hama in 1982. The similarity between that period and our time is immediately obvious, as Hezbollah and Iran’s growing support for the Bashar Assad regime has become the main target of the heated Sunni rhetoric against the Shi’a.

The fervent anti-Shi’ite polemics in recent years have been primarily fueled by fear of losing Sunni hegemony, spreading to an enormous extent thanks to internet technology. The polemics are concerned with three issues: theology (for instance, the Shi’a’s attitude towards the first Muslims and recriminations in which each side accuses the other of distorting the Quran), religious law (for instance, the Shi’ite legalization of mut’ah, temporary pleasure marriage), and history (for instance, portraying the Shi’a as a manifestation of paganism that dates back to the Jahiliyya and of Persian animosity towards Arabs). Through these issues, Sunni radicals seek to expose “the true face of the Shi’a”.

The following are several examples of Sunni polemic arguments against the Shi’a:

- The idea of rapprochement (taqrib) is nothing but a conspiracy created by the hypocrite Shi’ites to lull the Sunnis with slogans of conciliation while enjoying a free reign to turn them into Shi’ites. Therefore, conciliation with the Shi’ites is only possible if they give up their faith and become Sunnis.

- The Shi’ites harbor a deep animosity towards the Sunnis, particularly the Wahhabis, instead of joining ranks with them at a time when Muslims are facing a ferocious Christian-Jewish attack from the outside. This argument is a response to those heard from Arab intellectuals about the anachronism of the sectarian conflict in light of the “Western attack”. On the contrary, the Sunnis say, the ball is in the Shi’ites’ court.

- Taqiyya, the custom of concealing one’s true religious identity that is practiced by Shi’ite Muslims, is the complete opposite of the idea of “sanctification of God”, which is the duty of every Muslim believer. There is no clearer indication that the Shi’ites are “the most deceptive sect” (akzab al-tawaef), as they are referred to by the 14th century Sunni theologian Ibn Taymiyyah, one of the greatest luminaries of Sunni radicals.

- The Shi’ites have adopted heretical ideas from the Jews. For instance, the Shi’ite mehdi is simply the Jewish false prophet, who makes claims to divinity but in fact represents Satan. That mehdi speaks Hebrew and his rule is based on “King David’s shari’ah” — a new Quran that was distorted during the time of Talmudic scholars. What is more, it is the Persians and the Jews who concocted the Shi’ite-Sunni conflict, particularly a Jew from Yemen who sparked sectarian tensions during Caliph Othman’s reign.

- The Shi’ites are worse than the Jews, since the Jews have no wish to convert the entire world to Judaism, but the Shi’ites want to enforce their faith on all human beings.

- The Shi’ites are nothing but Persian Zoroastrians (majus, or magi) in disguise, not Muslims. They even make pilgrimages to Kashan to visit the tomb of the Persian slave who murdered Caliph Umar. The Persians have destroyed the pure Arab Islam (it is quite conspicuous that the traditional Salafi hatred of Ottoman Turks has been redirected at modern Persians as a result of Iran’s dominance).

- The Shi’ites have betrayed Islam throughout history: they surrendered Baghdad to the Mongols and, after the occupation, behaved like “rabid dogs” in that city; they tried to murder Saladin; they worked with the Europeans against the Ottomans and are responsible for the failure of the Ottoman siege of Vienna, which marked the beginning of the end of the Muslim empire. The same is true today: the occupation of Iraq in 2003 was the work of the Shi’ites, who used American assistance to topple the regime and spread their faith. “The outcry should be about a Shi’ite cross, not a Shi’ite crescent”, Sunni polemicists say.

Of course, the Sunni polemic arguments are mostly entirely baseless, distorting the sources and having no foundation in history. At times, the Sunni radicals even rely on Western researchers — who suddenly become legitimate — to bash the Shi’a. Those conspiracy theories that blame the Shi’ites for all that is wrong with the world spare Sunni Muslims the need for soul-searching and for actually dealing with their own problems and failures throughout history.

The anti-Shi’ite rhetoric reached a peak with Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, Al-Qaeda’s previous leader in Iraq. He departed from previous practice by calling for a total war against the Shi’a in Iraq — to the extent of a genocide, in fact. His announcement drew criticism even from such prominent jihad theoreticians as Maqdisi and Tartusi, who certainly have no great love for the Shi’a. They did justify attacking Shi’ites but prohibited the killing of all Shi’ites, explaining that not all Shi’ites collaborated with the Americans against the Sunnis.

Such differences of opinion among global jihad leaders were (and still are) an indication of the gap between philosophy and practice. Perhaps the reservations about Zarqawi’s stance were politically motivated, and perhaps they have their source in the difference between clerics who are drawn to the idea but are still bound by psychological inhibitions, and the unfettered go-getter mentality of a war bully like Zarqawi. Either way, the reservations voiced by the jihad philosophers had no effect on the actual slaughter taking place on the ground, and Zarqawi’s extremist rhetoric is still felt years after his death. The current reality in Iraq, where the number of casualties in the Shi’ite-Sunni struggle is skyrocketing, is evidence of that.

In the Sunni anti-Shi’ite polemics, there is continuity between arguments from different periods. Ibn Taymiyyah was and still is the first and foremost source of inspiration for Sunni radicals, with Ibn Abd al-Wahhab a close second. The arguments they made at the time against the Shi’a are still voiced, unchanged, by their followers. That, however, should not be put down to adherence to history as a scientific discipline. What matters is not the past, but the way it is used for present needs. Therefore, the arguments against the Shi’a are to a great extent ahistorical, and even “orientalist”.

The Shi’ites, on their part, also slam the Sunnis with conspiracy theories that have no basis in reality. Each side’s allegations are often a mirror image of those made by the other side. The Sunnis refuse to acknowledge the changes undergone by the Shi’a and completely ignore the differences between the various Shi’ite schools of thought. There is also a considerable resemblance to anti-Semitic claims: for instance, a Sunni belief in the existence of “The Protocols of the Clerics of Qom”, mistakes of Shi’a faith explained simply by the fact that it is the Shi’ites who make them, and other ideas along similar lines.

In the current political and religious reality in the Middle East, the anti-Shi’ite diatribes do not remain confined to rhetoric, but are translated into demonization and actual violence. This can be seen in the Syrian civil war and in the spillover of sectarian violence from Syria into Lebanon.

![]()

Note:

[1] For more details on Al-Qaradawi’s speech, see the June 26, 2013 article: “Yusuf al-Qaradawi Calls on Muslims to Support the Rebels in Syria”.

RSS

RSS

[…] As a new report by the Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center puts it: […]

[…] 2). The Sunni-Shi’ite Schism is One of the Most InfluentialFactors in Current Middle East Conflicts June 26, 2013 https://www.crethiplethi.com/the-sunni-shiite-schism-is-one-of-the-most-influential-factors-in-curren… […]