![]()

Mon, Sept 12, 2011 | Turkey Analyst, vol. 4 no. 17 | By Richard Weitz

The View from Beijing: Growing Chinese Enthusiasm over Turkey

This article was first published in the Turkey Analyst (www.turkeyanalyst.org), a biweekly publication of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center. © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center, 2011.

Chinese analysts have been pleasantly surprised by the stupendous growth in their cultural, economic, and political ties with Turkey after the Cold War. They describe both China and Turkey as two emerging powers that are now entering a new strategic partnership that could reshape Eurasia. Chinese scholars consider Turkey an increasingly important country for China due to its growing economy, increasingly independent and influential diplomacy, and pivotal location between Europe, Eurasia, and the Middle East.

Background

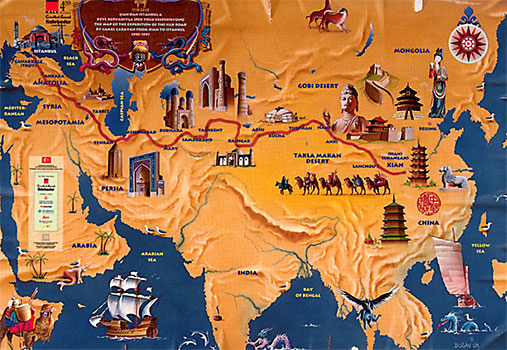

Chinese academics and officials stress Turkey‘s geopolitical importance to China. They note that Turkey is a Turkic-speaking nation closely linked with Central Asia, a Middle Eastern country whose regional influence has been rising, and a member of the NATO and EU candidate (and in terms of some economic conditions that interest the Chinese more than that). Beijing has strived to improve relations with the Turkic peoples, including in Xinjiang, considers the Middle East and especially Central Asia as regions important for China’s development and security, and is aiming to improve ties with both NATO and the EU. Turkey can serve as a conduit for China to exert both direct and indirect influence in these other regions.

In addition, Chinese analysts view Turkey as one variant of the rising number of overly Islamic oriented governments arising in Eurasia and the Middle East. They also perceive Turkey as the best of these variants, contrasting Turkey’s moderate, stable and secular political system with the less stable regimes in their client state of Pakistan and the aggressively extremist form of Islamic government seen in Iran. They prefer that the Arab Spring yield more governments like Turkey rather than more regimes like Pakistan and Iran.

China’s Turkey specialists express grudging admiration for the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) despite suspicions of its overtly religious ties. They note that Turkey’s AKP-led government has pursued a more independent foreign policy than its predecessors that has seen Turkey distance itself from the United States and especially Israel. More recently, the AKP has deftly developed good ties with the governments of Libya and Syria and then abandoned them when these regimes have fallen into trouble. Although they express suspicions about the AKP’s sympathies for their fellow Muslims in Xinjiang, they accept that Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s harsh comments following the July 2009 ethnic riots were made for domestic political reasons—to resonate with the popular sentiment in Turkey against Beijing’s crackdown. They note that Erdoğan quietly sent his special envoy, State Minister Zafer Çağlayan, the following month to Beijing, who expressed understanding for the Chinese policies and hope that the incident would not undermine bilateral ties. They further note that Erdoğan refrained from denouncing China’s Uighur policies when Prime Minister Wen Jiabao visited Turkey in October 2010. The Chinese and Turkish governments agreed to establish a strategic partnership, again manifesting Erdoğan’s policy of forgetting about the Uighurs in order to develop bilateral sate-to-state ties with the People’s Republic of China.

A current Chinese fear is that religious and other ties could serve as a transmission belt for importing Middle Eastern chaos into the Muslim-majority nations of Central Asia and potentially Xinjiang, with its large Muslim Uighur minority. Central Asian countries are also energy suppliers but are more important to China due to their proximity and the growing Chinese investment in Central Asia, whose governments are more inviting to Chinese businesses than those of the Middle East, where Chinese companies most often engage in projects under contract. In fact, the Chinese worry that the new Arab regimes will not respect China’s commercial interests due to their collusion with Western governments to constrain Chinese business opportunities in these countries. Another concern is that the Middle Eastern disorders, which Chinese experts believe will last for months if not years, will help keep world oil and other commodity prices unnaturally elevated.

Chinese analysts hope to exploit what they list as the many reasons Turkey wants to improve bilateral ties. First, Turks want to develop economic ties with China, especially to sell goods and attract Chinese investment. Secondly, Ankara is exploring developing further military ties with the People’s Liberation Army. Thirdly, China is a leading world power. For example, its status as a permanent member of the UN Security Council gives Beijing considerable say over issues of concern to Ankara, including Cyprus, Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, and the Middle East peace process. Fourth, China’s economic and political influence in Central Asia is growing; and Turkey wants to work with Beijing to increase their mutual influence in this important region, which Chinese analysts emphasize could serve as a bridge between their two countries. Both governments have expressed interest in elevating Turkey’s ties with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which Beijing uses to co-manage Central Asia with Moscow. Fifth, Chinese officials do not attack Ankara’s policies towards the Kurds, talk about an Armenian Genocide, criticize Turkey’s repression of media freedoms, or otherwise seek to interfere in Turkey’s internal affairs. Finally, Turkey has failed to achieve problem-free relations with Europe, the Arab states, Iran, or Israel. Aligning with China could help Ankara gain leverage in these other relations as well as compensate for these strained ties.

Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao (L) shakes hands with Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Ankara on Oct 8, 2010.

Implications

China’s Turkey specialists argue that their relations with Turkey have made considerable progress despite many obstacles. For example, traditionally a major source of tension has been Beijing’s treatment of its ethnic Uighur minority in Xinjiang. The Uighurs are a Turkic-speaking Muslim minority in western China and share religious, ethnic, historical, and other ties with the other Turkic peoples of Central Asia as well as Turkey itself. For decades, Turkish governments offered asylum to Uighur migrants, some of whom established associations advocating independence for what they called the state of East Turkistan. These included the Eastern Turkistan Cultural Association, the Eastern Turkistan Women Association, the Eastern Turkistan Youth Union, the Eastern Turkistan Refugee Committee, the Eastern Turkistan Islamic Movement, and the Eastern Turkistan National Center. Many Turks have sympathized with the Uighurs as victims of Chinese communist persecution. When the Turkish nations of Central Asia gained independence in the early 1990s, many Turks hoped those in Xinjiang would soon follow suit.

But by the end of the decade, Turkish officials had ended their practice of giving Uighurs leaving the China automatic Turkish citizenship, recognized Xinjiang as an inalienable part of China, and forced many independence-advocating East Turkistan groups to close shop or leave the country, often to Germany or the United States. In December 1998, Prime Minister Mesut Yilmaz banned Turkish officials from participating in anti-Beijing activities relating to East Turkistan. Beijing rewarded Turkey’s new Uighur policies, as well as its restrained response to the June 1989 Tiananmen Square killings, by not criticizing the Turkish government’s use of military force in Kurdish areas. The Chinese government also adopted a neutral stance toward the Cyprus issue.

Both Turkish and Chinese officials have since prioritized the values of territorial integrity, national sovereignty, and the fight against what officials in Beijing denounce as the “three evil forces” of transnational terrorism, ethnic separatism and religious extremism. The disappearance of their common Soviet threat and the independent national economic reform processes in the two counties, which aimed to integrate them more into international markets, also led both governments to focus more on developing bilateral economic connections even as new political issues emerged that led to more joint discussions: the newly independent Central Asian countries, the Middle East peace process, Afghanistan, the Iraq War and the war in terror. During his April 2002 visit to Turkey, Prime Minister Zhu Rongji and his host Bülent Ecevit signed four agreements, including a China-Turkey Agreement on Customs Affairs Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, which was soon followed by the establishment of a Joint Economic and Trade Committee. During the next decade, bilateral trade tripled, reaching $1.2 billion in 2010. Growth areas included energy, transportation, metallurgy, and telecommunication.

Conclusions

The China-Turkey relationship looks set to become even more important in coming years, both independently and to each other, due to the two countries’ status as rising global powers and their current governments’ inclination to embrace new partnerships and opportunities. In the view of Chinese analysts, the close cultural and historical affinity between the Uighurs in China and other Turkic peoples should enable them to serve as a bridge between China and Turkey as well as Central Asia.

Although China’s trade with the Turkic nations remains low in relative terms, and dwarfed by China’s enormous commerce with other regions like East Asia, Western Europe, and North America, trade with Turkey and Central Asia is nonetheless important for not least Xinjiang, since its peripheral location has limited the region’s trade ties with China’s larger markets. Chinese plans to import more Caspian Basin oil and natural gas will fortify Xinjiang’s westward orientation. Turkey may eventually also become more important for the rest of China since the two countries’ national economies are expanding much faster than the global average, and have sustained exceptionally high GDP growth rates despite the global recession, elevating their global economic importance.

Richard Weitz is Senior Fellow and Director of the Hudson Institute Center for Political-Military Analysis. He is the author, among other works, of Kazakhstan and the New International Politics of Eurasia (Central Asia-Caucasus Institute, 2008).

RSS

RSS

The View from Beijing: Growing Chinese Enthusiasm over Turkey | Middle East News, Articles, Backgrou http://t.co/oaiiawXb

The View from Beijing: Growing Chinese Enthusiasm over Turkey | Middle East News, Articles, Backgrou http://t.co/oaiiawXb

The View from Beijing: Growing Chinese Enthusiasm over Turkey – http://t.co/Kv8nM8aC