![]()

Mon, May 16, 2011 | Turkey Analyst, vol. 4 no. 10 | By Peter G. Laurens

Turkey’s Economy: A Trump Card for the AKP in the June Elections

© Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center, 2010. This article was first published in the Turkey Analyst (www.turkeyanalyst.org), a biweekly publication of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center.

Less than a month from now, Turkish citizens will go to the polls to cast their votes in the Republic’s seventeenth general election. Economic problems are often the catalyst for political change worldwide and in Turkey this is no exception, but in the country at present there is precious little bad economic news for opposition parties to exploit in attempting to weaken the ruling party’s chances at victory.

Background

Many pundits have predicted a sweeping victory for Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) in next month’s general election. Driving this forecast is the observation that major segments of the populace are willing to credit the AKP with good stewardship of the economy over the past decade of impressive economic growth. Regardless of the degree of real causality between Turkey’s economic growth and the AKP’s policies over its two terms in power, many voters are seen as unwilling at present to transfer the reins of fiscal and monetary policymaking to opposition parties who are either associated with past blunders, or whose ideas are simply untested.

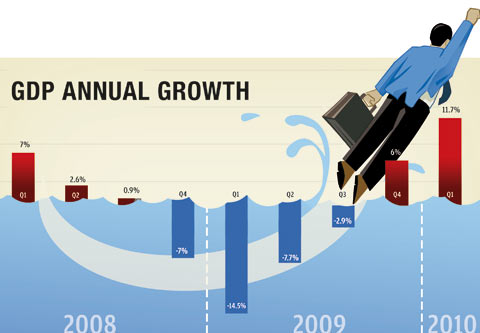

Remarkably, Turkey emerged from the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 relatively unscathed. While Turkey’s GDP in 2009 did suffer a contraction of about 5 percent, this was largely due to the spillover effects of illiquidity in financial markets around the world, and not from any lack of prudence on the part of Turkey’s economic and fiscal policymakers. In fact, over much of the previous decade, Turkey’s public and private sectors both had put into effect policies rooted in serious lessons learned from the country’s 2001 economic crisis.

The government executed an ambitious policy of reform which included fiscal tightening, the introduction of a floating exchange rate, increased privatization and massive support from the IMF. As a result, public debt levels fell from nearly 70 percent of GDP in 2002 to under 46 percent in 2009. Runaway inflation, Turkey’s greatest economic bugaboo for many decades, was a chief policy concern during the post-2001 period of economic reform. Instrumental in reducing inflation rates was the granting of independence to the central bank in 2001. The bank set formal targets for inflation in line with GDP growth estimates and concomitant expansion in the money supply. As a consequence, the inflation rate plummeted from 53.5 percent in 2001 to 6.3 percent in 2009.

At the same time, much of the corporate sector adopted prudent management of credit exposures and cash reserves. Thus when the global crisis hit in 2008, neither government nor private businesses were as vulnerable to external shocks as they might have been in the absence of preparation. Because of the relatively high interest rates set by policy, Turkey experienced growing capital inflows over this period, noticeably in the form of portfolio investments. Turkish banks saw rapid growth in assets over the previous decade and the sector overall remained strong during the crisis. Moreover, the rebound in GDP was strong in 2010, with an estimated growth rate of 7.8 percent, among the fastest in the G20. (Some estimates have Turkey’s GDP reaching the US$ 1 trillion mark by end-2011.)

Implications

However, as the Turkish lira has appreciated due to these inflows and stimulated domestic demand for imports, now, at the end of this ‘decade of reform,’ Turkey is faced with a growing current account deficit, estimated to be over 5 percent of GDP in 2010 and forecast by some to hit 8 percent in 2011. While running current account deficits for years on end is considered a serious problem for a country borrowing heavily in the short-term foreign debt markets, the likely end result — a collapse of confidence in the country’s finances — can, in the absence of corrective measures, be masked or held at bay for years by high domestic demand and by exogenous factors propping up the currency’s value.

So Turkey’s ruling party finds itself in the enviable position of heading into an election in the midst of an economic boom which many people consider it responsible for, but whose possible negative end results — a ‘hard landing’ with inflation resurging, capital flowing out and credit contracting — are not even on the ‘radar screens’ of most voters at this time.

The latest figures for foreign direct investment (FDI) provide some insurance against a revival of gloom, at least in the short run. After plummeting at the height of the financial crisis in 2009 to about a third of its 2007 level of US$ 22bn, FDI rebounded markedly by the first quarter of 2011, and is forecast by some observers to return to pre-crisis levels this year. This is a positive development, as it indicates that the balance of foreign investment in Turkey is shifting from portfolio money toward deeper capital commitments. The dry statistics are supported by abundant on-the-ground evidence of burgeoning activity by large, foreign companies in Turkey’s domestic markets, in a wide variety of businesses such as automobile manufacturing, food processing, and tourism.

Another very visible hallmark of Turkey’s rapid GDP growth in recent years is the veritable explosion in the growth of credit — at an annual rate of between 30 and 40 percent. This growth has been most noticeable in personal consumer loans. While the proportion of nonperforming loans is said to be very low, nevertheless at the end of 2010 Turkey’s central bank began to rein in the lending activity of commercial banks by raising the reserve requirement on short-term lira deposits; this action was repeated four times over the past months, sending the reserve ratio to 16 percent by this April. These actions compel the banks to deposit more cash at the central bank and lower the amount they have available to lend out. In addition, in January of this year the central bank cut its benchmark repo rate to a low of 6.25 percent, a move intended to discourage speculative inflows.

The problem is that recent financial policy maneuvers by the AKP government have collided with the demands of a consuming public that is expanding in both sheer size and in willingness to spend. As the purchasing power of the population grows, the government is finding that it is very difficult to slow loan demand by fiat.

Conclusions

In the run-up to the June elections, Turkey’s economy is experiencing remarkable growth, both in quantifiable terms and in popular perception. Any pressures building beneath the surface — the specter of inflation, the growing current account deficit, unsustainable consumer lending, the fickle nature of FDI flows as shown by the recent crisis — remain the bailiwick of economists, bankers and other specialists for now, and are simply not of sufficient concern to the public to affect the outcome of the elections. Under such circumstances, it would be difficult for opposition parties to effectively use the economic situation as leverage against the ruling AKP in the elections.

Indeed, the political momentum provided by steady economic growth over the past several years will put the wind in the sails of whichever party winds up the electoral victor. Interestingly, when reflecting on how much importance the question of Turkey’s accession to the European Union has had in Turkish politics over the past years and decades, it is extraordinary to see this issue now taking a back seat. There are two main reasons for this. First, a decade of rising GDP has dampened the sense of urgency within Turkey for pursuing the accession issue. Second, the European Union itself is currently preoccupied with managing extremely important debt crises in several of its member states; these crises have fortified already existing strains of skepticism within Europe for Turkey’s entry into the Union.

After the election however, the new Turkish government will likely find it necessary to ramp up efforts to prevent the economy from overheating. This means adopting economically restrictive policies that, at least in the short term, will probably run counter to the prevalent spendthrift mood of many of the nation’s consumers. The new government would do well to look at the sorry economic experience of much of the developed world during the past three years and send the Turkish economy a message that excessive spending can easily lead to future privation.

First and foremost, the banking authorities must restrict further runaway growth in consumer credit. The government needs to bring more economic activity out of the shadows and into the formal sector, to direct more tax revenue into its coffers. Provided that fiscal prudence is maintained, this would help to ensure the creditworthiness of the public sector, and guard against the possibility of a renewed reliance on external financing in general and fickle portfolio capital in particular.

Peter G. Laurens is a consultant in risk management for the financial industry, with a professional background in Emerging Markets investments.

RSS

RSS

Latest Comments

Hello Mike, Thank you for your positive feedback to the article. I felt there wasn’t too much critical analysis of ...

Thanks for this considered and well constructed article. A follow up article on the manner in which the editorial contro...

THE CLUELESSNESS OF CLAIMING THAT OBAMA'S MIDDLE EAST POLICIES WERE A FAILURE CANNOT BE FURTHER FROM THE TRUTH, WHAT THE...

As long as Obama is the president of the usa do not trust the us government......

Thank you for an good read....